Will Japanese crisis curb the rise of nuclear power?

- Published

Explosions and fires have further destroyed the Fukushima nuclear power plant in the wake of the earthquake and tsunami

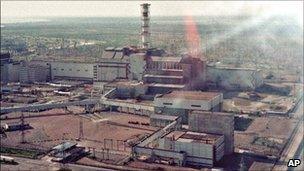

Until late last week - when the earthquake and tsunami in Japan caused a nuclear emergency on a scale not seen since the Chernobyl disaster in 1986 - it was taken for granted that nuclear power would become increasingly important across the world.

Obviously, with renewed concerns about the safety of nuclear power causing many countries to reconsider their plans, the latest predictions about the industry's growth may no longer be accurate.

Yet an International Energy Agency (IEA) prediction, external of a 49% rise in global energy consumption between now and 2035 remains unchanged.

Which poses the question: Can this anticipated surge in demand for energy be met without building more nuclear power stations?

Slower progress

The nuclear industry and its proponents have long insisted that its services are a vital part of a broad overall energy mix, especially in fast-growing countries such as India and China whose economic development relies heavily on electricity supplies being expanded and improved.

Indeed, even now with a nuclear disaster unfolding in Japan, any talk of the demise of atomic energy might seem churlish.

"I do not think it is going to derail nuclear new build," observes Alex Barnett, analyst with investment bank Jefferies.

"But definitely in Europe and in the United States, there will be a slowing of nuclear plans, maybe cancellations."

New nuclear power plants

According to the the IEA's World Energy Outlook 2010, nuclear power's share of the total energy market will grow even more rapidly than the market itself.

Hence, by 2035 its share of global energy production should have risen to at least 8% from 6% in 2008 according to one of its estimates, with a prediction under another scenario suggesting nuclear power could soon deliver about a fifth of the world's energy requirement.

Under none of the scenarios will nuclear power become a dominant source of energy. Indeed, none of the increases may sound that great.

But even the least dramatic prediction, from 6% to 8%, would suggest that nuclear capacity would expand by a third if the energy market was to remain stagnant.

Given that the overall energy market is predicted to grow by about a half, the nuclear industry's generation capacity would need to almost double over the next quarter of a century for it to outgrow the market and thus reach its predicted market share.

Ambitious plans

A number of governments have responded to the currently heightened concerns among their electorates by suspending the approval processes for new nuclear power stations to revisit safety standards.

The nuclear industry has come a long way since the Chernobyl plant was built

In each case this will probably result in reports being written, reiterating assurances that modern nuclear power plants are perfectly safe - especially in countries that are not seismically active. There may well be heated debates in many countries,

But in the end, many - perhaps even most - of these new build projects might well go ahead as planned.

Indeed, ambitious new build plans outlined by countries around the world make it clear that even if some of them were to pull back a bit, the industry's expansion will be considerable.

Most established nuclear power nations are gearing up for new build programmes, and there are plenty of newcomers.

"We expect between 10 and 25 new countries to bring their first nuclear power plant online by 2030," predicts Yukiya Amano, director general of the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA).

"Currently, there are probably 11 or 12 countries that are actively developing the infrastructure for a nuclear power programme."

New and old reactors

But if the Japanese crisis might do little to stall the nuclear bandwagon that is already on a roll, it may well result in more withdrawals of agreed extensions to the lives of ageing power stations that had already been scheduled for closure - as was done in Germany this week.

Extensions to such power stations' lives were originally agreed in order to meet anticipated power shortages and to reduce the use of fossil fuels to help meet different countries' carbon dioxide (CO2) emission reductions commitments.

Cancelling such extensions will thus both push up electricity prices and, as coal, gas and oil use increases, result in an overall rise in CO2 emissions - at least in the short-run.

Such decisions would nevertheless reflect a view shared by many, both from within the industry and among nuclear power opponents, namely that old nuclear power stations are considerably less safe - or more dangerous - than new ones.

The explosions and the near-panic in Japan offer proof that "low-cost nuclear reactors are not the future", according to Anne Lauvergeon, chief executive of nuclear reactor maker Areva, who was interviewed by the television channel France 2.

Nuclear reactor evolution

The basic idea behind a nuclear reactor is pretty simple. Nuclear fission, generally fuelled by uranium or plutonium, heats up water which evaporates. The steam turns turbines, which in turn drive electric generators.

There are a number of different reactors in use, most commonly water-cooled pressurised or boiling water reactors - though other reactor types are kept cool with the help of liquid metal, gas or molten salt.

Whether nuclear power is safe or not will be debated for decades yet

There are no clear-cut definitions about which reactor type is the safest, however.

Instead, reactors are deemed as having become safer over time thanks to the evolution of designs and safety technologies.

The way the Chernobyl reactor did not have a concrete armoured containment shell, which the Japanese reactors do have, is one example of how reactor design has improved and become safer over time.

People who work in the nuclear industry talk about Generation I, II and III reactors, with most Generation I reactors already being phased out.

Along with supposedly being the safest on the market, so-called Generation III reactors have longer lives than Generation II, they are therefore supposed to be more cost effective to build and run, and they are said to produce less nuclear waste.

The safety improvements relate to simpler designs with some modern reactors having fewer pumps, valves and motors than old reactors - meaning fewer things can go wrong.

Modern reactors also tend to rely on passive safety features that use natural forces such as gravity, circulation or evaporation rather than relying on active systems such as pumps, motors and valves.

"The designs we are offering today are reactors that will not release radioactivity in the air, even in the very unlikely event of a meltdown of the core," according to Ms Lauvergeon.

Such an assurance might well be accepted by nuclear proponents.

But with the Japanese situation still out of control, it will do little to mollify the fast-growing herd of sceptics.