Social media capitalise on Russia's history of censorship

- Published

The monthly audience of the Russian segment of the internet is estimated to be 50 million users

When it comes to self publishing, writers and readers in Russia have more experience than most.

In Soviet times, the phenomenon of samizdat - the Russian word for self publishing - was the only way for many to make themselves heard in an environment strictly guarded by the Soviet propaganda machine.

Moreover, it was one of very few ways, along with word of mouth and the BBC Russian Service's radio programmes, to learn about things the Soviet censorship wanted to keep secret.

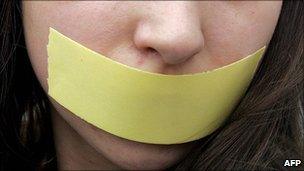

But then, during the 2000s - after a decade of almost total freedom of speech in Russia - the state significantly increased its control over mass media.

It was only natural for many people to respond by embracing the new culture of online blogging.

"Samizdat is part of the society [in Russia]," says Annelies van den Belt, chief executive of Moscow-based online media company Sup.

Her company owns blogging site LiveJournal, the Cyrillic segment of which has almost five million registered accounts, making it a leader among blog hosts in the Runet, as Russians often call their segment of the internet.

A recent survey puts the monthly audience of the fast-growing Runet at 50 million.

"There are more than 40 million blogs in the Runet, but only 7-10% are active - that is, updated at least once a month," says Dmitry Chistov, chief analyst at the Russian Association of Electronic Communications.

Globally, blogs have been losing the battle with social networks, but in Russia they are holding their ground much better, although, Mr Chistov admits, the peak of their popularity was reached in the 2000s.

Mikhail Geisherik, social media department director at Grape Advertising Agency, says that the main difference between the Russian and Western blogospheres is the fact that the Russian one "is hugely politicised".

"Basically, it is the most active part of the [global] blogosphere," he says.

Different behaviour

Mr Geisherik estimates the audience of blogs in Russia at about 15 million people, less than the one of predominantly local social networks (30 millions) and the audience of Russia's online advertising market, "which almost equals the number of the Runet users".

The Russian Association of Communication Agencies says the country's online advertising market rose 40% in 2010 to 26.7bn roubles (£580m, $940m).

Ms van den Belt says that her company, which she calls a "premium digital media business", as the websites it owns employ many professional journalists in addition to running user generated content, has "predominantly advertising business model".

Opposition activists say that Russia's mass media are strictly controlled by the state

She says that no less than 90% of the company's revenue comes from advertising.

Generally speaking, the same business model is used by most online media companies.

But Mr Chistov points out that as blogs visitors behave different from readers of news websites, the format of advertising could also be different - and more effective.

"On a news website, people usually read an article and leave the page, while they could end up spending a lot of time on a page containing a blog post, participating in a discussion," he says.

"As a result, you could show them not just a typical advertising banner, but a video banner; not a standard contextual advertising text, but one containing a joke or a specific web slang."

Apart from advertising, which is the biggest single source of income, social media companies in Russia have started making more money from selling additional services to users.

"This is what separates social media with their huge audiences from most Russian internet websites [in terms of making money]," says Mr Geisherik.

In turn, Mr Chistov says that unlike their Russian counterparts, many foreign blog hosts, such as Tumbler, Posterous and Wordpress, have a very cautious approach to advertising, instead making more money from selling additional services, such as premium accounts, as well as blog themes and templates.

New reality

The popularity of blogs and, as a result, the profitability of a blogging site are mainly based on who the writers are and what they write about.

"It is all about content," says Ms van den Belt.

As is the case with many other blog hostings and social networks, very different prominent figures have LiveJournal accounts - from the Russian President Dmitry Medvedev to the outspoken anti-corruption campaigner Alexei Navalny.

"The most active and popular bloggers are almost media now, with their own 'editorial policy' and the regularity of postings," says Mr Geisherik.

"Companies wishing to enter the Russian social media market should understand that the secret of success lies in poaching the leaders of blogging, and that is what Facebook has been doing successfully," he adds.

Ms van den Belt points out that the speed with which new platforms such as iPad have been appearing creates the need for social media businesses to adapt much faster than before.

The road to success, she believes, is combining content created by users of social media with traditional journalistic output.

Mr Chistov agrees that as the internet experience has been getting more and more mobile, not all blogging services fit into this new reality.

"Blogging sites have found their niche in the media environment and are now trying to integrate into the new age of social networks," he says.