The price of Mexico's 'drugs war'

- Published

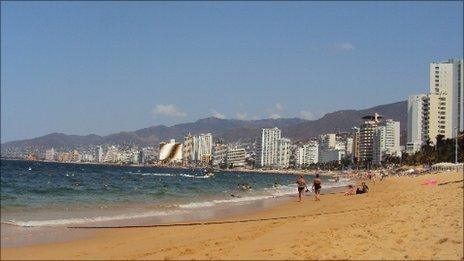

Acapulco, one of Mexico's prime tourist destinations, is taking a hard hit from drug-related violence

War, it is said, comes at a cost - not only in human lives, but also on the health of a country's economy.

Mexico, fighting a bloody war against drug cartels, seems unscathed by the conflict - but doing business in the country is not easy for everyone in times of rising crime.

Mexico's economy is growing solidly - 5.5% last year - and optimistic expectations continue well into this year, a healthy recovery from the effect the US recession had on its neighbour's economy.

Mexican Finance Minister Ernesto Cordero recently told the BBC there was "no evidence" to suggest investors were being put off by the conflict sparked by the presence of organised crime groups using the country as a route to transport narcotics into the US.

As for tourism, one of Mexico's largest earners of foreign currency, "we have very high rates of occupancy, so it doesn't seem affected," Mr Cordero said, adding that the focal points for violence were not areas usually visited by tourists.

Tell that to Acapulco's hoteliers.

Reputation hit

The resort on the Pacific Coast, one of the country's main tourist destinations for domestic and foreign tourists, has become a battleground in the fight against organised crime.

Nearly 700 people have died in drug-related incidents since 2006 in the city, and shoot-outs between rival drug cartels and with the security forces are frequent.

Foreign tourists have not been targeted and the hotel district has been mostly spared by the violence - but headlines around the world of "Acapulco's descent into violence" have badly tarnished the city's reputation.

Sitting among deck chairs around the swimming pool at the Copacabana hotel, chief concierge Jose Luis Espejel admits that tourism is on the decline.

He talks about the "spring breakers", the US university students who from late February to early April flock south of the border for warm temperatures and beach parties.

Following warnings by some in the US against travelling to parts of Mexico, external, Acapulco was off the radar for spring breakers in 2011.

Mr Espejel says that while last year about 2,600 students filled the rooms of his hotel, this year only 60 showed up. Official figures from Acapulco's authorities say the number of spring breakers that came this year dropped by as much as 93% compared with 2010.

That has had a huge impact on the city's livelihood.

"There are no jobs," he says.

"Low occupancy, no income, obviously no profits. And these are not only hotels - everybody has problems, restaurants, bars, even people selling items on the beach."

Positive

According to government figures, about 22 million tourists visited Mexico in 2010, an increase of 4.4% compared with 2009.

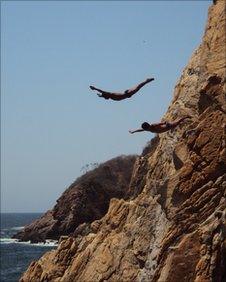

Acapulco's divers are one of the city's main tourist attractions

Critics say that the increase is nothing to celebrate - since the number of tourists entering the country had plummeted in 2009, when Mexico became the first country in which swine flu was reported.

Other areas of the economy are showing healthier indicators.

The announcement, earlier this year, by the US retail giant Wal-Mart, that it would invest more than $1bn (£615m) in the Mexican market was lauded by the government as yet another proof that foreign investors were not being scared off by rising crime.

Antonio Ocaranza, spokesman for Wal-Mart Mexico, says that while they had noticed some changes in people's purchasing patterns - for instance, in some areas of the country they avoided shopping after dark because of security concerns - their sales continued to grow.

"We see that beyond the current circumstances that affect some cities of the country, I believe this is a country that, beyond what is happening now, has enormous growing possibilities."

In fact, Mexico ranked high in a World Bank report on the ease of doing business, external - amount of hurdles to set up a company or access credit, among other criteria - it was the top-ranked country in Latin America.

Unemployment in Mexico is the lowest in all of the Americas and one of the lowest between member countries of the Organisation of Co-operation and Economic Development (OECD).

'Extortion fee'

But some argue that even if Mexico's economy is showing good signs, the violence could be preventing it from growing even more.

Recently, a chief economist for the BBVA Spanish bank - a major investor in Mexico - put a number on it.

"If there were no violence, the Mexican economy would have grown 1% above the rates of the past few years," said analyst Jorge Sicilia from BBVA.

This is attributed by many not only to investment in extra security measures for companies, but also to the fact drug cartels have morphed into sophisticated organised crime groups, spreading their business to kidnapping and extortion.

A survey by the American Chamber of Commerce in Mexico, external of more than 500 business leaders revealed that 67% felt less safe doing business in Mexico compared with last year.

The Canacintra national manufacturing industry chamber recently estimated that up to 10,000 small and medium enterprises had shut down during 2010 in the areas most badly affected by the drugs violence.

Many of them had suffered extortion or threats from criminals who demanded the payment of a "fee" for their security.

That is the case for a businesswoman in Central Mexico, who prefers to remain anonymous.

She told the BBC that six months ago, she and her husband, owners of a successful medium-sized company, had been approached by a group of armed men who identified themselves as members of the La Familia drug gang.

They asked them to pay about $4,000 (£2,465) every month - and threatened to kill them and their family if they did not.

Fearing a retaliation from the criminals if they alerted the authorities, they decided to pay.

"They show up every month to collect the fee," she says, visibly nervous while walking around a park in Mexico City.

These episodes make many in Mexico fear that, as the drugs war rages, other parts of the country could start living the turmoil that Acapulco is already facing.