Hong Kong hopes minimum wage will narrow wealth gap

- Published

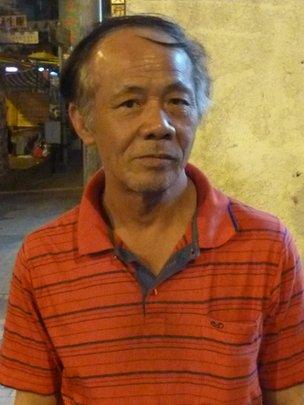

Mr Lam is one of 270,000 Hong Kongers expected to benefit from the introduction of a minimum wage

Graveyard sweeper Lam Wai Kau is looking forward to a pay rise.

He plans to spend some of the extra 500 Hong Kong dollars ($64; £39) he will receive each month when the territory's new minimum wage is introduced on a slap-up dinner.

"In five years, I don't think I've eaten pork more than a dozen times and fish never," he says one evening after finishing work.

Mr Lam is one of the 270,000 Hong Kongers, or 10% of the working population, expected to benefit when the minimum wage of 28 Hong Kong dollars ($3.60, £2.18) per hour takes effect on 1 May.

It will mostly affect cleaners, security guards and those working in restaurants and catering.

It is the most notable of a number of recent steps Hong Kong's government has taken as it comes under pressure to narrow the territory's widening wealth gap.

"With inflation and the cost of living rising, low-income workers really have a hard time feeding a family," says Lee Cheuk-yan, president of the Hong Kong Confederation of Trade Unions and a legislator.

Free enterprise

Hong Kong has long been a bastion of free-wheeling, laissez-faire capitalism and the minimum wage legislation has been fiercely resisted by the business community, who fear it will erode the territory's competitive edge.

Business leaders say the level is too high and may force small businesses to lay off staff.

"We have always have been a free enterprise economy and let the market decide what is best," says Cliff Sun, chairman of the Hong Kong Federation of Industries.

"Now we are twisting this."

He says that 45,000 people may lose their jobs as a result of the wage legislation.

"The level is way over the capability of a lot of small and medium firms."

But union leaders, who had proposed 33 Hong Kong dollars an hour, say that these fears are overstated given Hong Kong's low employment rate and the buoyant state of the economy.

Long fight

Unions first began campaigning for a minimum wage in 1999 after the Asian financial crisis led to a cut in wages.

The government says a lukewarm response by businesses to a voluntary minimum wage scheme in 2006 forced it to introduce the compulsory legislation.

However, Hong Kong is late in adopting a minimum wage compared with elsewhere in the region.

With the exception of Singapore, most Asian countries now have, or are planning, minimum wage legislation in some form.

Even before it takes effect, the new law has sparked heated disputes as some employers have been taking pre-emptive action to avoid a higher wage bill.

The new law does not specify if rest days or meal breaks should be paid at the minimum wage.

This has led to some workers being rehired on new contracts with unpaid lunch hours and rest days. Others have been switched to being hourly rather than monthly paid staff.

Mrs Cheung, who did want to give her full name because she feared her boss would object to her speaking to a reporter, says she has been forced to sign a new contract that reduces her working hours by 2.5 hours a week.

And because she will be treated as a new hire she will have no rest days for two months and her annual leave will be reduced.

"It's not really an improvement," she says.

Tycoon cleaner

Not all members of Hong Kong's business community have opposed the legislation.

Michael Tien, chairman of Asian fashion chain G2000, was once a big believer in letting the market have a free hand, but he says his views have changed over the past decade as Hong Kong's wealth gap has widened.

He became more convinced earlier this year after he worked and lived as a street cleaner earning 25 Hong Kong dollars an hour as part of a television programme.

He spent three days sweeping up cigarette butts, litter and fallen leaves with a bamboo brush and heavy metal cart.

"People are really being exploited even though our economy has been booming," he says.

Mr Tien, who is also deputy chairman of the New People's Party, hopes the minimum wage will encourage Hong Kong businesses to increase productivity and thereby make the economy more, not less, competitive.

"With the correct equipment, it could take a cleaner one hour to clean a block not two hours."

"You pay more but you need less people."

Daily struggle

Rising living costs mean the minimum wage will not lead to a massive improvement in the daily struggle of many low-paid workers.

Sat on a bench in the public housing estate where she lives and works, 63-year-old Lau Yuk Na says her monthly income will rise from 6,300 Hong Kong dollars to 7,800.

"The pay rise won't make much difference to me," she says, complaining about the price of cooking gas and bus fares.

The grime under her fingernails, visible as she hands out slices of pomelo, is testament to the six days a week she works as a street sweeper.

An immigrant from mainland China, she says she regrets leaving her homeland 15 years ago for Hong Kong's neon lights but doesn't see any alternative but to carry on working.

Her sons only give her a little money each month and she needs to save in case she gets sick in her old age.

"I don't know how to read or write. What else can I do?"

- Published23 February 2011