Tackling Africa's economic problems

- Published

Ashish Thakkar will become the first man from East Africa to enter space

Ashish Thakkar will be East Africa's first ever man in space.

A Ugandan businessman and astronaut, he has a place on a flight of the Virgin Galactic programme.

This sci-fi image of Africa perhaps seems counter-intuitive, but it represents a new confidence and a desire to re-brand the continent in the eyes of the world.

The spaceship that will send Mr Thakkar to the stars will be launched thousands of miles away in Philadelphia, but it represents a desire for the continent to be taken seriously in an increasingly hi-tech world.

Africa is experiencing growth rates that are exceeding the global average, and foreign direct investment has increased by more than 80% in the past decade.

"It's a great time for Africa," grins Mr Thakkar. "It's a time to focus on taking advantage of our natural resources and gain from technological knowledge transfer."

Sourcing own power

But getting products out to customers in many countries in Africa continues to be as big a challenge as sending a man to the moon.

"Forty per cent of agricultural produce perishes on the way to market," says Professor Mthuli Ncube, chief economist and vice president of the African Development Bank.

Microsoft's Mteto Nyati says Africa has a skills problem

He says infrastructure, especially transport and power, will be the single biggest factor that helps transform the continent.

The World Bank estimates that $93bn (£57bn) worth of infrastructural investment is needed in Africa. That includes everything from roads, railways and schools to reliable energy sources.

Many businesses in Nigeria have taken to developing their own power sources because the national grid cannot be relied on - despite the country's considerable oil wealth.

Without these bare essentials operating costs remain high, making businesses uncompetitive. But less than half the amount needed is actually being spent on infrastructure, and grand cross-border projects sometimes hit the buffers.

Prof Ncube concedes part of the challenge is down to operational problems. Legal hurdles can impede the rolling out of big projects across national boundaries.

And poor leadership has caused many infrastructural initiatives to remain pipe dreams.

Yet the roll-out of technological infrastructure - like the East African cabling system which provides fibre optic cables from Mombasa to the United Arab Emirates - demonstrates the enormous potential to transform a region.

Not only is the project a template for public-private partnerships, but it has also provided a platform for thousands of new tech-based businesses to grow.

Everything from computerised real-time mapping services like Ushahidi in Kenya, to telephonic banking services which are set to expand massively in the region, have sprung up on the back of this kind of development.

And on top of that, the middle classes are becoming a rapidly growing domestic market for home-grown services.

Agricultural advantage

But Africa needs to be cautious about adopting an Asian model of business development in a bid to stave off their markets being flooded by cheap Chinese imports.

That's a view that's increasingly gaining traction in Africa's business world.

Many believe Africa should concentrate on building up its agriculture sector

Mteto Nyati, managing director of Microsoft South Africa, argues that with 70% of the population on the continent living in rural areas - and roughly the same number under the age of 30 - the emphasis must be on creating jobs in areas where Africa has resources.

"We have a problem with skills, so I don't think we necessarily should be looking at manufacturing expansion and too much large scale hi-tech," he says.

"[We should] look at where we have a comparative advantage and it is in agriculture. We should be feeding the rest of the world."

He wants Africa's leaders to study best practices in areas such as agriculture and emulate them, rather than being seduced by the model of China.

"We cannot be China, we don't have a billion people, we have got people who are illiterate, we have to train them so we have to look at agriculture," he says.

But he fears the continent's leaders have yet to drive this through. Farmers are leaving countries like South Africa and being hired for their skills further north, at a time when Africa could be feeding the world.

Social entrepreneurship

On the demand side, Africa is seeing a growing domestic market with a middle class that now represents about 34% of the continent's population.

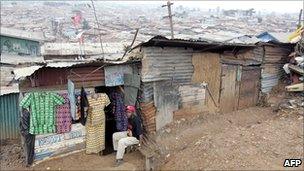

Some social entrepreneurs are offering help to pull people out of poverty

But the African Development Bank warns that more than half of them risk slipping back to join the poorer classes unless their spending and earning potential is harnessed.

A growing middle class buys mobile phones, travels in cars and requires housing. Yet mortgages have been risky business in a continent which has been prone to instability. Now though in East Africa mortgage markets have been on the rise.

The demand for cheap houses has attracted the innovative flair of the social entrepreneurship sector.

Social entrepreneurs like Aleke Dondo step onto the scene when "market fails", to use the economic jargon, often leveraging funds from donors to establish operations, which in time will flourish into fully-fledged revenue-generating businesses.

Aleke's project in Kenya provides low-cost mortgages to former slum dwellers to pull themselves out of poverty, asset financing for smallholder farming, and rural banking services in areas where previously there were none.

"We need the government to help create an enabling environment to help initiatives like these to flourish," he says.

Do this for a period of five years and you will really start to see change, he says.

Tackling unemployment

But one of the biggest challenges for the coming decade, with a huge political price tag attached, is how to create more jobs.

South Africa may be the powerhouse of the continent but it is also one of the most unequal societies in the world - one in four people is unemployed, according to official figures - and right across the continent unemployment breeds instability.

Coupled with perceptions of poor leadership, as we've seen in North Africa and more recently in Uganda, and it can prove positively toxic.

Some commentators see Kenya's Raila Odinga as heralding a new style of leadership in Africa

South Africa's Jacob Zuma has pledged to create five million jobs and cut unemployment by 15% by 2022, but getting a quality workforce requires good education.

Geoff Rothschild, director for the Johannesburg Stock Exchange, puts education right at the very top of the continent's priorities in helping to groom the next generation of workers.

But it requires leadership and commitment, and Mr Rothschild is among the optimists who see a new style of political leadership slowly emerging in Africa.

He's clearly impressed about a new generation of leaders such as Kenya's Raila Odinga and Zimbabwe's Morgan Tsvangarai.

Both prime ministers were forced into uncomfortable power-sharing deals, from which many hope they will emerge humbled rather than vengeful.

Both men will face elections next year so let us wait and see the results.

The vast majority of Africans have yet to feel the direct benefits of growth rates of 5.5%.

But what is beginning to emerge is a consensus over what should be the priorities to sustain such growth and ensure that this - as so many analysts are saying - is Africa's decade.

- Published6 May 2011