Inside the world of China's super-rich

- Published

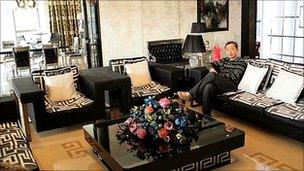

China's fantastically rich are well catered for

Who are the leaders of China's economic miracle? Where do they come from, and what are their wildest ambitions?

A hundred years ago it was the likes of Rockefeller, Ford, Carnegie who were building the future.

With China closing in on America to become the world's biggest economy, the next century belongs to names like... Zong... Dai... Liu.

We had better get used to it.

As I read ever-more hyperbolic accounts of the Chinese economy, its impact on global trade, and the spending spree of its newly rich middle classes, I wanted to find out about the men and women who are leading this transformation.

I was not after the bosses in government and the Communist Party, although they are pulling the levers in their state-controlled society.

I was seeking the people behind the country's explosive economic growth - the top entrepreneurs.

They are the ones building world-beating companies, leading China's export success and creating new jobs by the million.

Thirty years ago the Party denounced entrepreneurs as: "self-employed traders and peddlars who cheat, embezzle, bribe and evade taxation."

Then the line changed. Deng Xiaoping, the driving force behind the move to capitalism after Mao's death, famously declared ''to get rich is glorious''.

Benign Capitalism?

One of China's richest men, Zong Qinghou says he lives on $20 a day

Karl Marx himself had a soft spot for entrepreneurs. In Das Kapital he asserted that workers were exploited by capitalists who profited from the added value of their labour.

But he argued entrepreneurs, although still capitalists, added their own value - through their fresh ideas and ability to seize opportunities.

Entrepreneurs, at least the good ones, were benign capitalists, said Marx.

That explains their rehabilitation in post-Mao China. But they are still expected to play their part in a centralised system.

I wanted to get behind the corporate announcements and the carefully managed public appearances to see how China's super-rich actually live, to hear what they really think and to try to understand why they had risen to the top of society, rather than their 1.3 billion fellow-countrymen and women.

What do they feel about the vast mass of China's population? How are they coping with their wealth. What are their plans for the future?

Liu Yi Qian, born into a working class family in Shanghai, is now China’s biggest art collector

As they talked openly about their fortunes, their path to the top, their hopes for their own children, and the prospects for the world's fastest growing economy, I felt I had just begun to penetrate behind the mask of inscrutability which is the default mode for all Chinese dealings with foreigners.

The billionaires I spoke to had all risen from total poverty. Not relative poverty, compared, say, to a typical Western family.

They had known the sort of poverty where there was not enough to eat, and each day was filled with grinding labour.

Traditionalist or aristocrat

Now they have made their fortunes, they divide into two types, depending on their attitude towards money and luxury.

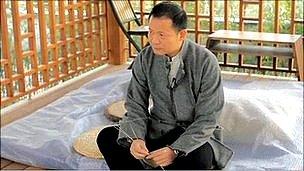

The first type, you might call the "Party Traditionalists". They are typified by Zong Qinghou, boss of drinks and clothing firm Wahaha, who when I met him was the reigning richest man in China.

As we sat facing each other across the desk in his modest office, he told me that the money he had made was for society, not for himself. And he emphasised that he eschewed luxuries.

The second group are exemplified by Dai Zhikang, a 40-something property developer. I call them China's "New Aristocracy".

They are more at ease with their new-found wealth.

Unlike the Russian oligarchs they tend to steer clear of vulgar displays of opulence, and in a sense they are making their new money into old money - buying art, travelling widely, buying property and sending their children to private schools and universities in Britain or America.

The next generation

Both types talked freely about the role their children might play in inheriting their fortunes.

Even the traditionalists reserved the right to entrust their wealth to the next generation, although only if the children could be relied upon to build on the fortune rather than fritter it away.

Dai Zhikang's spent his early years looking after pigs and cows in Jiangsu province

They were all aware that they had seized an opportunity that would never again be presented to the Chinese people - that it was easy to start a business during the transition from communism to capitalism - "the opening up" - much easier than now.

The other difference between the Party Traditionalists and the New Aristocracy was their attitude to luxury brands.

One of the younger generation proudly showed me his new $50,000 Patek Phillipe watch.

He had bought several he told me, because they keep their value. By contrast, a top Party man, an industrialist, wore his humble Citizen timepiece with equal pride.

The Traditionalists wore Chinese-made suits. The Aristocrats sported beautifully made casual wear.

Each of the entrepreneurs I met was near the top of the various rich lists that fascinate China's (and the world's) media.

In the near future it is quite possible that at least one of them will drop out through the ebb and flow of business success. But their eventual fate makes no difference to the insights I gleaned through meeting them.

As well as being fascinating characters in their own right, they allowed us to glimpse new China through their eyes, and understand the forces that will shape all our lives over the next decades.

Nick Rosen is head of Vivum Intelligent Media Ltd, external. He is making a documentary about the lives of China's top entrepreneurs.