Farmers look to pig poo to boost revenues

- Published

The farm's 4,000 pigs are contributing to the upkeep of the pens they live in

What to do with 12,000 tonnes of pig poo?

That's the question farmers James Hart and Jeremy Iles found themselves asking two years ago when contemplating how best to supplement their dwindling incomes.

Thanks to the buying power of the major supermarkets, pig farming is no longer as profitable as it once was, and Mr Hart in particular was looking at ways to make the most of the resources at his disposal.

The solution they came up with was beautifully simple; turn the huge amount of pig faeces generated on the farm - not to mention cow dung and chicken droppings - into hard cash.

The mechanism for doing so is, in essence, remarkably straightforward and could secure the future of the farm and the livelihoods of the 10 families which depend upon it.

Slow uptake

Glebe Farm near the sleepy village of Hatherop in Gloucestershire is an unlikely place to stumble across a state-of-the-art, million pound biogas station of which there are just a handful in the UK.

The plant can run 24-hours a day and output can be tailored to demand

The plant itself is wholly unremarkable to look at, but what goes on inside could help to revolutionise not just this farm, but hundreds of others just like it across the country.

In fact, the technology is proven and, given the government subsidies available, profitable.

It's just that, like with most renewable energies, the UK has been painstakingly slow on the uptake. In Germany, for example, there are thousands of similar plants.

Hot air

In essence, vast quantities of animal waste are mixed with lots of grass in a cylindrical tower - "basically a 3,000 tonne cow's stomach," says Mr Hart.

Bacteria then break down the mixture, producing methane, which is siphoned off, cleaned and filtered.

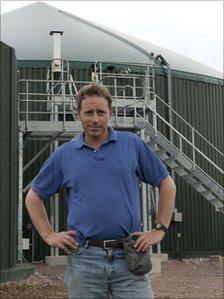

Mr Hart has bet heavily on the success of his new biogas plant

This gas is then used to power what is effectively a £200,000 Mercedes truck engine, which in turn powers a generator, electricity from which is fed into the National Grid.

A by-product of the process is large quantities of fertiliser that remain in the tower once the bacteria have worked their magic.

The heat generated by the process is also captured and used for central heating at the farm house. It is, then, in renewable-energy speak, an efficient 'closed-loop' system.

And the benefits to the farm are both numerous and substantial.

For a start, Mr Hart expects to be able to sell the 2.2 million kilowatt hours of electricity generated each year - enough to power more than 175 homes - for about £300,000.

Almost two-thirds of this money comes in the form of a green energy generation subsidy from the government - a perfectly standard arrangement for any new energy source, and one that will be reduced once plant costs come down.

On top of this, Mr Hart should save about £30,000 in fuel bills for the farm, and of course pay no heating costs at home.

In addition, he expects to buy about 200 tonnes less fertiliser every year, saving another £60,000.

And what's more, the process even removes almost all the smell coming from the manure.

Harmful gases

But it's not just Mr Hart's business that benefits from the plant.

The hi-tech biogas plant requires more than 3km (1.8 miles) of wiring to run

Methane is about 20 times worse than carbon dioxide in trapping heat in the atmosphere and so is widely recognised as one of the more potent greenhouse gases.

By capturing the methane produced by the waste generated by his 4,000 pigs, 100 cows and 100,000 chickens, Mr Hart expects to reduce his equivalent carbon footprint by about 10,000 tonnes a year. That's the equivalent of almost 9,000 return flights from London to New York.

He is also using far less fertiliser, which can be fairly carbon intensive to manufacture.

Hard times

In theory, then, the biogas plant could give Glebe Farm a much-needed new lease of life.

A standard truck engine adapted to run on gas runs the electricity generator

Mr Hart's father took on the farm in 1969 and was able to make a good living, but his son has found life much harder.

The price he receives for his pigs from the supermarkets is the same now as it was 15 years ago, and was significantly lower for much of the past decade.

With the cost of raw materials and labour, not to mention the price of bacon and pork in the shops, increasing significantly over this time, margins have been slashed.

Mr Hart needed to take drastic action to keep the family business going.

"I needed to find another source of income and I wanted to improve my environmental impact," he says.

He and Mr Iles considered wind turbines and solar panels, but soon realised planning permission would be tricky. Nor were they convinced either would produce enough power.

Farming has moved a long way from the more traditional manual-labour intensive tasks

Biogas generated from pig poo seemed the perfect answer - a "win win solution where we could extract an income from something we already had," says Mr Hart.

Getting planning permission was easy, but finding the necessary cash proved a great deal harder. "We had nothing but a very large overdraft," Mr Hart explains.

Despite a £300,000 grant from the Rural Development Programme for England and a payback of just four to five years, Lloyds was the only bank prepared to stump up the extra £900,000 needed to buy and fit the entire plant from low carbon energy firm Alfagy.

Beating targets

It may have been running for just three months, but, barring any unforeseen major maintenance costs, the early signs are good.

"We are ahead of schedule and have already hit our September bank targets," says Mr Hart.

Mr Hart hopes to use the profits from the biogas plant to upgrade his pig pens

In other words, the farm is back in business. There are no guarantees, but Mr Hart says that until such time as the supermarkets pay a fair price for his pigs, he will continue to rely on the revenue generated from his animals' waste, not just to support his family and those of his workers, but also to maintain his pigs.

"I'm not an environmentalist, I'm just a farmer who wants to be as green as he can be," he says.

"As farmers, we are always thinking of the next 30 to 40 years and we [at Glebe] are now fully committed for the next half a generation.

"We are custodians of the land and are just trying to leave it in a better condition than we found it."

Thanks to the biogas plant and of course his pigs that feed it, Mr Hart and his sons may now be in business long enough to do just that.

- Published11 October 2010

- Published16 September 2010