Inequality in China: Rural poverty persists as urban wealth balloons

- Published

Many in China's rural provinces are left behind as urban wealth grows quickly

The rapid growth of China's economy over the past three decades has been greeted with largely unquestioned assumptions that increasing affluence would lead to a happier, wealthier and more equitable society.

Of course, such assumptions came with an implicit acceptance that some would get rich faster, but also that these benefits would eventually trickle down.

The emergence of a middle class, combined with high levels of personal savings and low levels of personal debt, offers tantalising evidence of China's new-found wealth.

Yet, behind these headlines, there is compelling evidence that although economic growth has created vast wealth for some, it has amplified the disparities between rich and poor.

These disparities indicate an often hidden vulnerability in China's rapid growth, but one which is neither unique nor new to China's leadership.

Wealth Contradictions

One of the most fascinating contradictions of China's rapid growth under the auspices of the communist party has been the rapid emergence of private wealth.

The privatisation of state enterprises and the housing and social benefits that accompanied them, the re-zoning of rural land for industry, and a construction boom, created enormous possibilities for personal wealth.

The 2010 Credit Suisse Global Wealth Report noted that these forms of wealth, which accounted for much of the $9,600 in real assets per adult in China, were extremely important forms of wealth creation.

But they also came at a cost.

The report showed that although the average wealth per Chinese citizen was $17,126 - almost double that of other high growth economies such as India - median wealth was just $6,327.

The latter suggests that wealth created has not been evenly distributed.

Such inequalities also highlight a contradiction in that although the monetisation of previously state-owned assets undoubtedly benefited many of China's emerging middle class, it ultimately came at a cost to the public who would now have to finance these goods and services out of personal savings.

Divide between urban and rural ...

The wealth data, although a less rigorous measure of inequality, is also reflected in more conventional measures of inequality.

China's cities are growing rapidly

In 2010, China's Gini-coefficient - a measure of how wealth is distributed in a society - stood at 0.47 (a value of 0 suggests total equality, a value of 1 extreme inequality).

In other words, inequality in China has now surpassed that in the United States, and surged through the 0.4 level in the mid-2000s.

A Gini-coefficient of 0.4 is generally regarded as the international warning level for dangerous levels of inequality.

Looking only at the data for the whole country, however, conceals the growing disparity between urban and rural areas.

Even after three decades of rapid growth China remains a very rural economy.

Despite the continued growth in urbanisation, some 50.3% of China's mainland population (or 674.15 million people) continue to live in rural areas.

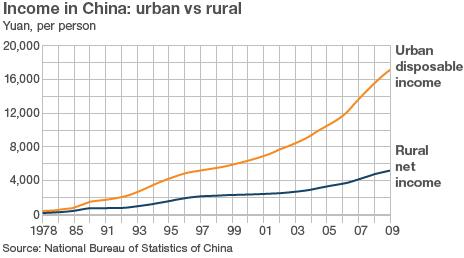

In 2010, rural residents had an annual average per capita disposable income of 5,900 yuan ($898). That's less than a third of the average per capita disposable income of urban residents, which stood at 19,100 yuan ($2,900).

As the chart shows, the gap between urban disposable and net rural income has persistently widened since 1978.

... is getting larger

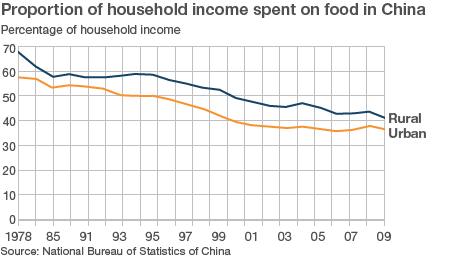

Disparities in income data are also reflected in household consumption patterns and the access those households have to basic consumer services.

The Engel coefficient, which measures how much of their income households have to spend on food, has been consistently higher for rural households.

Many cities, such as Beijing and Shanghai, now have coefficients lower than 30, reflecting the vast differences between these cities and the rest of China.

These patterns are hardly surprising, given that rural households must necessarily spend a higher proportion of income on food.

It is also unsurprising, given that even as late as 2009 three of China's poorest provinces - Tibet, Yunnan and Sichuan - were identified by China's banking regulator as having more than 50 unbanked counties.

This meant that they lacked even basic access to financial services.

What is surprising is how different urban and rural households are when it comes to durable goods such as cars, washing machines and fridges, considered normal essentials for households in the developed world.

More worrying is that the above trends may conceal an emerging rural divide.

The rural Gini-coefficient increased from 0.35 to 0.38 between 2000 and 2010, suggesting growing inequality within rural areas.

Of particular concern is the large pool of migrant labour.

At the end of 2009, China had an estimated 229.8 million rural migrant workers, of which about 149 million are thought to work outside their registered home area.

The official average monthly wage for these workers, many of whom work in manufacturing and assembly, amounted to 1,417 yuan, though unofficial reports suggest many earn less that 1,000 yuan a month.

Moreover, because these migrants work outside their registered area, the low wage rates conceal enormous personal sacrifices, which include long working hours, poor housing conditions, and, most significantly, a loss in welfare benefits associated with the household registration system known as Hukou.

A price worth paying?

The question for China is whether the scale of such inequalities is a tolerable price of growth.

Migrant workers are feeding China's economic boom, though some struggle to feed themselves

It is not a new question.

Even by 1978, urban per capita incomes were already growing at more than double the rate of rural farm incomes, and the post-1978 reforms appear to have further widened this gap.

It is clear that China's leadership has recognised how damaging such disparities can become in what is now the world's second-largest economy.

The government wants to lift some 40 million or so rural residents out of poverty; since 2004 it has worked to raise minimum wages for migrant workers, improve rural incomes through tax cuts and enforce labour contract law.

The Chinese leadership also tries to force labour-intensive and low-value added industries to move to rural areas.

Although such reforms have been described as a return to central planning or supply-side management, they suggest a recognition that the benefits of growth have not necessarily trickled down to Chinese society's poorest.