Who defaults first: Greece or the US?

- Published

- comments

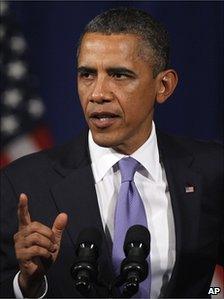

President Obama has called for significant spending cuts

Will the US government default on its debt before Greece does? The fact that I can even pose the question tells you we live in peculiar times.

With its next tranche of money from the IMF-EU bail-out now assured, we can say with some confidence that the Greek government will not default next month. Incredibly, the same cannot be said of the US Federal Government.

Just so we're clear: the world is a lot more dependent on the "full faith and credit" of the US than it is on Greece.

A default by the US government - even a temporary, "technical" default - would be a very serious matter, not only for the US but for the global financial system. That is why the smart money has always said it won't happen; that Congress and the White House would come to an agreement in the eleventh hour.

I am in Washington today, and I can report that the smart money is still saying this. It is probably right.

But we are now getting very close to the eleventh hour and - unlike the battle to authorise the budget back in April - this can't be resolved 20 minutes before the government shuts down.

From where we are, default is far from the most likely outcome, but it is certainly conceivable.

Raising the ceiling

By now you may be wondering how a serious country like the US could get into such a mess. Here's a brief recap.

Unlike most countries, the US has a legal limit on the amount the federal government can borrow, legislated by Congress, which is independent of the regular budget approval process.

Congress has raised that debt ceiling at least 75 times in the past 50 years, most recently at the start of 2010, when the limit was raised to $14.29 trillion (£8.92tn).

On 16 May, Treasury Secretary Tim Geithner declared that limit had been reached, and he was starting to implement "extraordinary measures" to limit the government's need for additional borrowing.

For example, he's not been issuing new debt to replace the bonds maturing in various federal employee savings funds, and he's retiring existing debt to pay certain civil service benefits, both of which give the government a little more headroom.

This kind of juggling ought to get them through to 2 August. After that, nothing is certain.

Growing deficit

The Bipartisan Policy Centre has looked at what's coming into the government coffers after that - and what's going out. It's not pretty, external.

In particular, 15 August looms large for the markets, because that's when $29bn in debt interest comes due. (There are four days a year when the Treasury makes most of its interest payments and that is one of them.) But there's a raft of other spending obligations that would come due before then.

Between 3 and 31 August, the think-tank reckons the federal government will have $172bn in revenues and nearly $307bn in spending commitments - meaning a deficit of just over $135bn. In theory, if the president can't borrow to fund that shortfall, he has to find a way to cut the government's outgoings by 44%. Overnight.

Many have suggested the Treasury could protect the government's credit status by simply prioritising debt interest and other essentials.

The administration says this is unworkable. It's not just that they'd rather not have to explain why they're holding back money from veterans to pay interest to Wall Street; why money market funds are more important than food stamps, say, or paying federal workers.

The larger problem, say Treasury officials, is that the markets would not take kindly to the government reneging on any of its legally mandated commitments, even those that do not directly concern the national debt.

That may or may not be correct. But, once again, you'd rather not put it to the test.

What's the way out of the impasse? "Simple", say Republican leaders. All the president has to do is agree to cut spending by $2 trillion over the next 10 years, without a penny in tax increases.

"Not so simple," replies the president. He's said yes to significant spending cuts, but raising tax revenues has to be part of the mix.

There have been plenty of twists and turns in the debate but that basic difference between the two sides still looms large.

Pubic opinion

Most Republicans in the House of Representatives will not vote for an increase in tax rates of any kind. That has put the focus on tax expenditures as the possible area for compromise - the loopholes and tax breaks which politicians claim to dislike but seldom vote to abolish.

Some senior Republicans are now hinting in this direction, external, though it's far from clear that their troops will go along with it.

Most economists - including the IMF, the OECD and most Wall Street analysts - reckon that the reform of major entitlements like social security and tax increases will be needed in any long-term solution to the deficit.

But if the polls are to be believed, few Americans do. Indeed, 70% say they don't want to raise the debt ceiling at all.

It's worth lingering over that poll finding. If accurate, it suggests that nearly three quarters of the American public don't want the US government to make good on commitments which a Democratic president and a Republican Congress have already passed into law, in this year's budget.

In such an environment, it's hard for politicians to do the right thing. Especially 15 months from a general election.

To return to where I began, the implications of a default are so serious, you have to bet the two sides will do a deal in the next three weeks, thus saving everyone the worry of a US default - at least until the next time. But plenty of damage will still have been done.