Are insurance referral fees a racket?

- Published

The large rise in insurance premiums has been blamed on claims for "whiplash" injuries

Amid the recent publicity about legal referral fees relating to car insurance claims, there has been more heat than light.

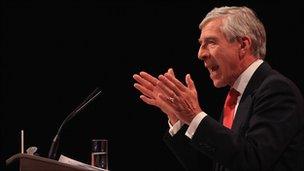

Critics of the practice, such as Jack Straw MP, have described it as a "racket" and a "dirty little secret".

In theory it should be neither.

The referrals system is essentially another way for law firms to market their services.

But it remains intensely controversial, and the government has pledged to reform it.

How does the system work?

The principle is simple - a law firm agrees to pay a fee in return for being passed the contact details of someone who might be interested in their services.

The deals are usually between lawyers and insurance companies, but estate agents and trade unions often refer their customers onto law firms too.

Law firms will pay up to several hundred pounds when someone who has been referred to them goes on to engage their services.

With sums like this involved, it is not surprising a whole industry has sprung up around it.

There are now claims-management companies who act as middlemen, buying contact details and then selling them on to law firms.

How long has it been going on?

Even though it has passed largely unnoticed until now, the referral industry has been around for 20 years.

Jack Straw gained an admission from an insurance executive that referral fees were a "dirty secret"

It started when the previously strict regulations on lawyer marketing were relaxed in the 1990s, as part of a drive to promote competition and reduce prices for the consumer.

Before this many people had seen solicitors as aloof and unapproachable.

Now lawyers have to advertise and fight for people's business like any other professional service.

Individual law firms have targets to hit and their sales teams are under pressure to win as many new clients as possible.

When trying to seal the deal, some will call a potential client a dozen times to ensure they return the necessary paperwork.

Cold calling

Many people object to being contacted, apparently out of the blue, by lawyers or claims managers touting for business.

If they have recently been involved in an accident, these approaches will often be particularly unwelcome.

The practice has led some to accuse the law firms who buy contact details from insurance companies of "ambulance chasing".

Selling personal details without a customer's permission is in fact illegal under the Data Protection Act.

An insurer who wants to pass a client's details onto a law firm must say upfront they have such an arrangement in place, and give the client the option to opt out.

Few of us realise when we buy insurance that such an agreement is often buried in the policy's terms and conditions.

By agreeing to them, we are also consenting to the insurer passing on our details in the event of an accident.

But a few unscrupulous claims-management companies have been caught cold calling and texting consumers when no such agreement is in place.

This is a clear breach of the Data Protection Act rules.

The backlash begins

The practice can be highly profitable for insurers, and a powerful way for law firms to win new customers.

So it is ironic the umbrella groups for both industries have called for it to be banned.

Both the Law Society, which represents solicitors, and the Association of British Insurers (ABI) have called for it to be ended.

But many individual insurers have come to rely on it as a useful source of revenue and are reluctant to lose it.

So far only one major insurer, the French-owned Axa, has pledged to stop accepting referral fees.

The Solicitors Regulation Authority, a legal watchdog, has called for solicitors to ensure any referral system "does not compromise their clients' interests".

In May the Legal Services Board, an independent body overseeing the regulation of lawyers in England and Wales, recommended the referrals system be made more transparent, but shied away of calling for an outright ban.

The government has pledged to reform it, while many opposition MPs are pushing for a ban on referral fees.

Why is a ban so controversial?

The government is worried the current system has created a US-style "compensation culture", in which people are encouraged to launch frivolous claims by law firms who have bought their contact details and are offering to work on a "no win, no fee" basis.

Those in favour of a ban say it would force lawyers to win clients purely on the basis of quality and cost, as well as bringing legal fees down.

Those against say it will make it harder for poorer people to gain access to justice, particularly if law firms are banned from working on a "no win, no fee" basis.

But even if referral fees are banned, it is unclear how effective a ban would be.

Past attempts have failed, and the prohibition of such a successful marketing arrangement is unlikely to succeed.

The best way for people to stop their insurers passing on their details to third parties is to opt out when buying a policy.

Or if you have already received an unwanted approach, you can contact your insurer to opt out of future third-party contact.

Handled correctly, the referrals system should be a useful marketing tool for lawyers, and nothing more sinister for consumers than a form of targeted advertising.

The opinions expressed are those of the author and are not held by the BBC unless specifically stated. The material is for general information only and does not constitute investment, tax, legal or other form of advice. You should not rely on this information to make (or refrain from making) any decisions. Links to external sites are for information only and do not constitute endorsement. Always obtain independent, professional advice for your own particular situation.

- Published28 June 2011

- Published27 June 2011

- Published11 March 2011