Formula 1 technology goes beyond the track

- Published

McLaren Applied Technologies helped improve the sleigh of the GB Women's bobsleigh team

As the roar from Formula 1 racing cars shakes Silverstone, home of the British Grand Prix, silent concentration reigns at the futuristic-looking base of one of the leading teams, Vodafone McLaren Mercedes.

This weekend, everything at this unusual car plant in Woking, Surrey, is about winning the race on Sunday, so technicians will be hard at work as usual.

But for one division of the McLaren Group, victory on the racetrack is merely a means to an end.

Meet McLaren Applied Technologies - a department specially dedicated to expanding the home-grown Formula 1 know-how into the non-F1 world.

Sure, other F1 teams also make products that are not directly related to Grand Prix racing - such as Red Bull's energy drink or Ferrari's roadcars.

McLaren's road car and Venge racing bike are probably the most well-known non-F1 products

But McLaren is focusing more on making money from the application of technologies developed for F1 cars to solve challenges off the racetrack.

McLaren's most famous product, besides its road cars, is probably the ultra-light carbon-fibre racing bike, Venge.

Developed in partnership with US cycling firm Specialized, it is said to be the fastest road-racing bicycle in the world.

"Their expertise in carbon technology and computing systems is exceptional," says Specialized research and development director Eric Edgecumbe.

"After spending just a short amount of time together we realised that we shared some very core, deeply held beliefs about winning at the highest level."

The partnership has yielded results.

The first time the bike raced, it won the Milan-San Remo race - which at 298km is the longest professional one-day race.

Advanced telemetry

But there are lesser-known areas of application, too.

One cutting edge technology is McLaren's advanced telemetry system, which uses sensors to monitor data feeds and thus enable real-time strategy and decision making.

"We've decided to take the aspect of remote condition monitoring of the car, and apply it to monitoring of people," explains Geoff McGrath, the head of the Applied Technologies department.

As he walks along a futuristic transparent walkway, suspended just under the ceiling, Mr McGrath says that the firm has already used this technology on patients undergoing a weight loss programme at a clinic in Norfolk.

The patients had medical sensors hooked up to them, transmitting data to the doctors.

"In the words of the people on the programme, they essentially had their GP with them, in their pocket," Mr McGrath explains.

"They could have continuous monitoring and also continuous interaction and feedback."

If patients are interested in an early warning, athletes might want to make vital improvements in performance.

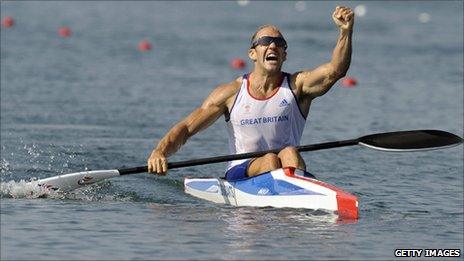

The technology has already been used to train UK athletes in a number of Olympic disciplines - for instance, in canoeing.

"McLaren's miniature sensors go inside the paddle, so every time an athlete applies force on the water, the sensor measures it and transmits the data back to see how fast the boat is going," explains Scott Drawer from UK Sport, a public body for directing the development of sport in the UK.

McLaren's sensors have been put in paddles to accelerate the athletes' rate of development

This instant feedback helps athletes make more informed decisions about when to rest and how to change techniques, thus accelerating their rate of development - and increasing their chances of success in competitions.

The sensors were also installed into the sleigh of the GB Women's bobsleigh team, which won the Women's World Bobsleigh Championships in Lake Placid, US, in 2009.

But applications in advanced telemetry can go beyond helping patients and athletes, says Mr McGrath. The system could be used, for instance, in a workplace.

"If you want your employees to behave well and deliver the best optimum results, wouldn't it make sense to take care of the holistic health, wellbeing, and work-life balance?

"Well, if you don't measure that performance and the conditions, how can you possibly optimise and deliver the best?

"For example, an executive who wants to deliver high performance... wants to know when his stress level is peaking, or know that he has not fully recovered after a bad night's sleep - and that he'd better be careful before doing a press conference on TV first thing that morning."

Virtual design

Another interesting application of F1 technologies is a motorsport simulator.

Not all racing teams have their own, but McLaren has two.

Williams' flywheel technology helps save energy

One is used to design the F1 race cars and train the drivers, letting them "drive" on virtual circuits, very much like playing an ultra-complex video game.

The second one, which is currently being built, will be used by other motorsport companies, as well as for the McLaren road car.

The impressive structure is formed of a huge semi-spherical screen that provides a 180-degrees view.

A seat is installed on rails in front of it, and a powerful sound system imitates the real-world environment.

Once seated, a driver gets a fully immersive illusion of driving, with the "car" moving like a real one.

"It is a system to allow engineers to design a car," explains Mr McGrath.

"They build a car in the virtual world, then put the driver in the virtual model and validate."

Saving fuel

But McLaren is not the only F1 firm interested in becoming a player outside the Grand Prix world.

Williams F1 has developed flywheel energy storage technology - an alternative to a chemical battery in hybrid cars - and it has been used to power the Porsche 911 GT3 R Hybrid.

AT&T Williams F1's chief executive Alex Burns says that the flywheel is a great way to save fuel - and it could be applied to city buses, trams and other vehicles that stop and start frequently.

"We're also developing a much larger version of this flywheel technology that can be used to reduce the total energy consumption of a metro train as it goes from station to station," Mr Burns says.

Williams has its own simulator too, which the company is also adapting for non-racing vehicles.

Reasons for expansion

F1 companies expanding outside the core of their sport have different reasons for doing so.

Williams, for instance, may be diversifying into non-F1 areas to secure new revenue streams and balance out its F1 income, according to Christian Sylt from Formula Money magazine.

But whatever the reasons, potential for "spillovers" is great - and Eric Edgecumbe of Specialized believes that it is critical for F1 teams to pursue it.

"They can learn a lot about what motivates people in their buying decisions, and they can also learn a great deal about what motivates F1 fans, and why they are attracted to and inspired by one team over another," he says.

But in the end, it all depends on the teams' strategies and the very reasons why they are on the track.

"Some really focus on the engineering and innovation. For others, it is more about visibility and brand recognition - they don't expect to win and may not anticipate applying the engineering developments," says Professor Rick Delbridge of Cardiff University, the author of a report on cutting-edge F1 technologies.

"And firms like Williams and McLaren are outstanding examples of British innovation and engineering, vitally important to the country's reputation beyond F1."

Williams Technology Centre, based in Qatar Science and technology park, is dedicated specifically to expanding into the non-F1 world

- Published4 May 2011

- Published25 February 2011