Kuwait's stateless Bidun demand greater rights

- Published

Kuwait classes Bidun as illegal residents

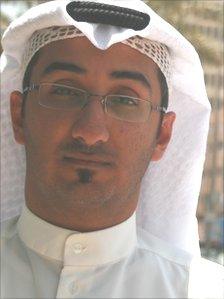

While his four young children play in the front room of their breeze block home, Lafi Al Lahfani is all smiles.

But after shooing them out so he can speak more openly, his expression changes as he talks of the difficulties of life as a Bidun.

It is the Arabic word for "without", and is the name given to communities of stateless people citizens across the Gulf, including some 120,000 in Kuwait.

While born here, Mr Al Lahfani is not recognized as Kuwaiti because his parents did not register with the government after the country's independence in 1961.

That makes it near impossible to get official papers - from birth and marriage certificates to a driving licence, identity card or passport.

And because the Bidun do not qualify for government jobs, he says he can find only irregular work that typically brings home about $600 (£373) a month or a little over $7,000 a year.

In a country where median income is $81,000 - before taking into account subsidised for housing and electricity that the oil-rich government offers citizens - he is firmly among the poorest

"I sometimes don't have enough money to buy the kids milk. The bottle is about $7.50 (£4.50) and I have to borrow the money, so when I say that we live below the poverty line I'm not exaggerating," he says.

"Sometimes, at Eid, we have no money to buy new clothes for the kids. As adults we are used to it. We wear anything we have, but the kids don¹t get it and they see other kids wearing new clothes and buying new toys."

Illegal residents

Mr Al Lahfani says about 50% of his salary goes on rent in the dusty suburb of Salibiya, one of Kuwait's poorest districts, and where its residents are almost exclusively Bidun.

Mr Lahfani fears his children have a "dark future"

It was here that in February and March this year hundreds of people took to the streets, at the same time as uprisings were occurring across the Middle East in places like Tunisia, Egypt and Bahrain.

But the Bidun did not want to overthrow a regime.

Instead, waving the country's flag and clutching pictures of the Emir, they demanded citizenship in the country they call home - and the rights and privileges that go with it - until police used tear gas and water cannon to quell the marches.

Kuwait officially classes the majority of Bidun as "illegal residents".

And opponents say many are from neighbouring countries such as Iraq and have destroyed evidence of their true nationality to try to get rights enjoyed by citizens, such as free healthcare and access to higher education.

Bidun groups insist this is true for only very few - adding that many have served the country in the army or the police force.

'Great deal of frankness'

A recent Human Rights Watch report, external criticized Kuwait for not delivering on promises to look at Bidun citizenship claims.

Mr Bader says that more Bidun may make their voices heard

And the government did not respond to BBC questions about its plans for improving the rights of the Bidun.

But since the protests, it has promised to make some concessions - from offering ration cards to reviewing access to public colleges and education.

And while saying he is unclear about how serious the government is in its intentions to act, Ghanem Al Najjar, political science professor at Kuwait University, says there are signs of progress.

"The issue of civil rights, social rights, economic rights, has been acknowledged by at least the majority of the parliament," he says.

"We have to look at this realistically and objectively. We hear a lot of talks, but is it going to solve the problem?"

After the Human Rights Watch report there was a press conference, which saw "a great deal of frankness", he adds.

"The Bidun were there. Some of the government were there. There were cross exchanges and this is something new."

Some of the progress Prof Najjar talks about includes the government taking the Bidun issue away from their interior ministry "meaning it's no longer a security matter".

And the new minister in charge has agreed that citizenship should be looked at "on a case by case basis", Prof Najjar observes.

But Bidun groups say that this does not happen beyond a few token cases, and that state bureaucracy more than counteracts any goodwill.

Kuwaiti citizenship

With unemployment high, men illegally sell melons alongside the roads leading into Al Salibiya and another predominantly Bidun district, Taimaa City.

They are fearful of talking, standing cautiously by their trucks, produce loaded ready to drive off in case the police come by.

Prof Najjar says greater economic inclusion for the Bidun would bring up to 60,000 people into the workforce, and he believes this would fit Kuwait's long-term plan to rely less on overseas workers.

But getting the right to work is not enough, says Nawaf Al-Bader of the Kuwaiti Bidun Gathering, a group representing the community.

"There are some basic human rights, like the right for healthcare, the right to work, the right to mobilise, the right to have identity papers, the right for education and travel," he says.

"These are the normal and basic rights for any regular human being living anywhere.

"But the most important right that we are asking for, and this is non-negotiable, is the right for a Kuwaiti citizenship."

Fighting for rights

Unemployment was one trigger for the Arab Spring in places such as Tunisia and Egypt.

And while the Bidun cause was different, Mr Bader says their protests had been inspired by the uprisings and predicts that more large-scale protests could come.

"It's a ticking timebomb," he says.

"The bomb hasn't burst yet and these are only sparks before the big explosion," he says, warning that while only a few thousand had protested last time, many more Bidun may find their voice.

"The events in the Middle East inspired the young Bidun to go out and ask for their rights - the rights that were taken away from them," he says.

It is a sentiment shared by Mr Lahfani, who gestures to the room next door where his daughter and three sons play with their mother.

He is hopeful those youngsters will get some of those rights, but he is not confident.

"We know already that our children's future is lost," he says.

"We know that there is no job for them, that no university will accept them. It's a dark future."