Online shopping is growing rapidly in China

- Published

As Nick Mackie reports, online shopping in China is more than clicking on the "buy" button

Zhang Qiaoli uses her spare bedroom for storing her stock of ladies' fashion-wear and photo shoots.

She is one of more than five million small online stores operating across China, some from small apartments or even college dormitories.

Zhang Qialoi runs her online business out of her spare bedroom

She buys dresses and accessories wholesale; using the website Taobao, she sells them on as the Kitty Lover range, at prices under $10.

Taobao is owned by Chinese e-commerce giant Alibaba and the brainchild of founder Jack Ma. It is a free-to-use online marketplace with some 800 million product lines - from food to clothes to technology.

It boasts 50 million unique visitors a day and is the top destination for three quarters of the country's online shoppers.

Running Kitty Lover allows Ms Zhang to work from home and take care of her baby son - though it's more than a hobby.

"Of course it's quite competitive, because there are hundreds of new stores opening every day on Taobao," says Ms Zhang.

"Considering that I haven't been doing this for that long a time, I need to gain experience and grow my own business step by step."

Across China, online companies large and small are learning how to be effective e-commerce players - or fail like US goliath eBay, which was trounced by upstart Taobao back in 2006.

In 2010, China's online shopping industry had a turnover of $80bn, and grew 87% year-on-year.

China's 420 million internet users spend around a billion hours each day online - and last year, 185 million made at least one online purchase.

According to Boston Consulting Group, the volume is expected to increase fourfold by 2015.

Online shopping now accounts for more than 5% of China's retail sales, and Taobao's sellers are behind 70% of the country's online transactions.

E-commerce is changing the way Chinese consumers think about shopping: online, it is more social than a hard sell. It's a new engaging experience to savour.

In Chinese retail, trust is a rare commodity. There are plenty of fakes online, and buyers are often cursed by scams or shoddy goods.

Still, consumer faith in e-commerce stores is remarkably robust.

That's because, apart from its convenience, online shopping has shifted the balance of power from sellers to buyers.

China's consumers have the upper hand like never before - and it's not just because there are more traders at their fingertips than in the local High Street.

Yang Jie built HanHan World through social marketing

Social commerce

HanHan's World sells what one might call chintzy Iphone covers. At its small office the team of three is busy chatting with potential customers via the site's instant messenger application, which also comes with video chat.

Customers can check how much HanHan's World sells and at what cost.

New sites on Taobao that want to compete with HanHan's World and move up the rankings have prove their worth by shifting volume and get good buyer feedback.

"In the beginning we promoted ourselves through product forums," explains Yang Jie, HanHan World's manager. "Due to good quality and our low prices, with barely any profits, we developed rapidly in a short time."

Online shopping in China is more than clicking on the "buy" button. The experience includes exchanging tips with other shoppers, discussing trends, and rating both products and service.

The interaction and communication generates trust.

"The ability of social networking combined with e-commerce or social commerce as I like to call it - where people are able to rate their providers, provide information to other purchasers - that level of experience is really overcoming the big weaknesses," says Duncan Clark, Chairman of BDA (China), an expert on China's e-commerce industry.

"Basically, there is a one-to-one connection being established. And that's breaking through the mistrust barrier if you will. So I think we can learn, actually - the West can learn from some of the developments happening in the Chinese e-commerce sector," says Mr Clark.

DangDang's Peggy Yu bets on the "latecomer's advantage

Latecomers' advantage

That said, even China's big e-commerce retailers, like Amazon look-alike DangDang, don't profess to be great technology innovators.

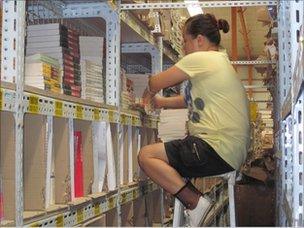

At its massive warehouse south of Beijing, most of the work is lifting, sorting, stacking, labelling, scanning, boxing, taping - before the trucks arrive to deliver 100,000 packages a day.

In China, the competition is about focusing on how to put the technology to work. This often means duplicating or tweaking existing ideas to get an edge in the market, cheaply and quickly.

"We should take latecomers' advantage," says Peggy Yu, chairwoman of DangDang. "To me that means, taking apart other success business stories and see how business can be conducted more effectively."

In this rapidly expanding, huge market of 600 cities, much of the focus now is on finance and management, and on solving the puzzle of how to deliver a fast reliable service to the regions far away from the eastern seaboard - and then grow market share.

In December 2010, DangDang - China's largest book seller - raised $272m by listing on Wall Street's Nasdaq stock exchange. The money was used to fund an expansion of its product range and establish regional warehousing.

DangDang's biggest problem is getting the supply chain to connect with its warehouses

But a big headache remains that is beyond the company's control: "I think the supply chain weakness is the biggest bottleneck to e-commerce in China," says Ms. Yu.

"Manufacturers in China are typically local businesses. And their distribution capacity is restricted to a very small region. But DangDang requires suppliers to deliver to our distribution centres throughout the country - so that we can ship to every single customer in the whole of China. And that is a real challenge for suppliers."

It's a fundamental offline problem for e-commerce in China.

Still, investors see China's scale and potential.

Another Amazon-styled mass market retailer, 360.buy, raised $1.5bn in April during a funding round - on top of a $500m investment round last December, that saw US retail giant Wal-Mart taking a stake.

What now, Taobao?

E-commerce in China is growing rapidly

At rival Taobao, these moves raised eyebrows.

Faced with a rapidly changing marketplace and freshly financed challengers with more focused product lines, in June parent company Alibaba split Taobao into three separate companies:

eTao, a shopping search engine, to help drive customers;

Taobao Mall, a fee-earning "online showroom" for some 70,000 companies, including many leading foreign brands; and, of course,

the Taobao marketplace for small sellers like Zhang Qiaoli to grow her fledgling Kitty Lover business - a platform that is free for users, although Taobao earns from adverts.

"I think, Alibaba is going through some growth pains right now," says Duncan Clark. "It's become so large, so fast with Taobao that it's having to seek ways to adjust. And it's not entirely clear yet how they'll emerge."

Some analysts go further and warn that the split could be disruptive.

Alibaba's top managers are not used to criticism. But the group lost a lot of long-held goodwill during what one could describe as founder Jack Ma's "annus horribilis".

First, staff of Alibaba's international business-to-business online market place were caught up in a $6m fraud.

Then came widespread criticism of the transfer of Alibaba's valuable online payment company Alipay to a firm owned by Jack Ma himself. Foreign investors like US firm Yahoo and Japan's Softbank were furious.

Both matters have been resolved, but a bitter taste remains - despite Jack Ma's insistence that he shunted Alipay from Alibaba to comply with new Chinese regulations that bar foreign ownership of any payment company on the Chinese mainland.

"The whole episode has been damaging... to Alibaba's perception in the marketplace," says Mr Clark. "They should be communicating more now about what's going on."

The BBC tried for three months to schedule an interview with Alibaba and Taobao, to discuss the fundamental changes rippling through China's world of e-commerce.

So far, neither the parent company nor its subsidiary found time to talk.