Libya's key challenges for economic stability

- Published

Estimates for bringing Libya's key oil sector back to pre-conflict levels vary between 12 months to three years

As Colonel Gaddafi's grip on Libya draws to an end, the chief questions are how stable will a new regime be and how can its economy be secured?

Success on one front is entwined with the other.

Libya, in theory, is a relatively rich country. According to the International Monetary Fund (IMF), income per head is a relatively healthy $11,300 a year, putting it well into the top third globally.

Oil and other natural energy resources are the lion's share of this, providing 25% of gross domestic product and 95% of export earnings. The country has 41bn barrels in oil reserves, the highest in Africa.

These earnings lead to the development of the country's sovereign wealth fund, the Libyan Investment Authority (LIA), which has estimated assets of $65bn (£40bn) in a broad swathe of businesses that include a stake in the Juventus football team, London West End property and other share stakes, including one in the owners of the Financial Times newspaper, Pearson.

Gold, too, is in abundance. The IMF estimates it has reserves of 4.6m ounces, worth about $8bn, among the highest per head of population holdings in the world.

As the former central bank governor Farhat Bengdara puts it: "We don't need donors. Libya is a rich country. The state activities from the Libyan Investment Authority, the central bank and gold reserves are worth $168bn. But it is all frozen."

Supportive partners

On top of that, other countries are keen to take up investment opportunities in the country, with candidates topping the list including Qatar and Italy.

Qatar is interested in extending its influence in the region. It has given huge support to the rebels' cause and was the first Arab state to support the no-fly zone in Libya.

Italy, as the former colonial ruler, is Libya's biggest trading partner - taking 38% of exports and providing 19% of imports. On top of that, its oil company, ENI, has valuable assets within Libya - assets that it needs to put back to use.

The money in theory is there. But there is a lot to be done once the fighting is contained.

The $65bn assets of Libya's sovereign wealth fund includes a stake in Juventus football club

Jane Kinninmont, senior research fellow at the international affairs body, Chatham House, sums them up: "There are three main concerns: one is security. One problem will be disarming the young men who have been fighting. They will have to be offered incentives - one-off payments perhaps, but longer term they will need job opportunities.

"Two is corruption. There have been serious problems in Iraq, which also had great potential. The other is distribution of wealth. The new government will have to strike a balance between bringing in investment while building Libyans' belief they themselves have a stake in the country."

'Waxy' oil

Oil and gas are central to all three issues and are certain to remain the highest priority for both the National Transitional Council (NTC) and foreign investors.

The International Energy Agency (IEA) says: "The country's oil industry was highly dependent on foreign companies but many will be slow to return until the situation on the ground is completely safe."

Libya's oil facilities were hurriedly closed and their foreign workers evacuated as the conflict escalated earlier this year.

The IEA says Libya's oil type is "waxy", which can cause significant damage to hastily shuttered equipment and wells if shut in for a long period of time.

Italy's ENI is wasting no time in returning to its assets. Libya supplies a significant 13% of Italy's natural gas needs and ENI is keen to help the country get back on its feet.

Its chief executive, Paulo Scardino, said ENI would begin supplying Libya with petrol diesel fuel as soon as possible and would eventually be paid in crude oil.

But ENI said it would take between 12 and 18 months to get oil back to where it was before the uprising, and its short-term focus would be on gas extraction.

Too early

But putting the energy sector back in business, particularly the oil side, could take far longer.

The energy research company Wood Mackenzie said in a research note this week that it could be three years before oil production was back up to pre-conflict levels of 1.6m barrels a day from the current 60,000 barrels.

"It is too early to expect a material recovery in Libya's oil and gas production. Once a resolution is reached, we believe it will take around 36 months for oil production to recover."

It said a return to business-as-usual in oil depended on a swift end to hostilities, and an early focus by the NTC and international community on stability and infrastructure repair.

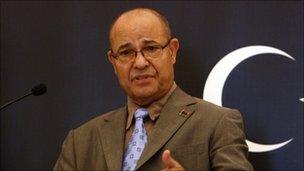

As for infrastructure, that will take at least 10 years, according to the head of the NTC's Libyan Stabilisation Team, Ahmed Jehani.

Mr Jehani said Libya's infrastructure was in a poor state even before the revolution because of "utter neglect".

Foreigners favoured

But reconstruction of bricks and mortar will only help so far.

Chatham House's Jane Kinninmont pointed out that most sections of economy were underdeveloped because the country was under sanctions for so long.

She says the regime has also underdeveloped another key resource - its people.

The vast majority - 59% - work for state-run businesses, with industry employing 23% and agriculture 17%.

She says the state will need to maintain or even increase this level of state employment while it develops its people's skills.

"Education is an issue. Education spending has actually been relatively high - literacy rates [at over 70%] are high by African and Arab standards, but what has been taught is not very useful learning for jobs.

"Libya has a lot of foreign workers - Egyptians and Tunisians were favoured by foreign companies in Libya pre the uprising."

These workers left the country amid the turmoil and luring them back will not be easy, she says.

"They will expect higher wages, at the least."

Frozen assets

The head of the NTC's Libyan Stabilisation Team: "Utter neglect" of infrastructure

Wood Mackenzie said it would take six months to get them back.

But, it also said there were other concerns than that: "Libya's oil fields are located in the vast, remote Saharan desert, making them impossible to defend from attack."

There will be some who will not invest for reasons other than security.

Gazprom, Gazpromneft, Tatneft and Russian Railways are currently working in the war-torn country. All of those companies made multi-million investments in their Libyan project.

Protests in the capital had centred on Green Square and various key buildings, like the headquarters of state TV and the People's Hall, were attacked and damaged. But Libyan leader, Muammar Gaddafi, and his supporters are very much in control of Tripoli. Colonel Gaddafi has appeared several times on television from his compound in Bab al-Azizia making defiant speeches condemning the protests.

The Libyan Army is a weak force of little more than 40,000, poorly armed and poorly trained. Keeping the army weak is part of Colonel Muammar Gaddafi's long-term strategy to eliminate the risk of a military coup, which is how he himself came to power in 1969. The defection of some elements of the army to the protesters in Benghazi is unlikely to trouble the colonel. His security chiefs have not hesitated to call in air strikes on their barracks in the rebellious east of the country.

Libya produces 2.1% of the world's oil. Since the protests began, production has dropped, although Saudi Arabia has promised to make up any shortfall. The high revenue it receives from oil means Libyans have one of the highest GDPs per capita in Africa. Sirte basin is responsible for most of Libya's oil output. It contains about 80% of the country's proven oil reserves, which amount to 44 billion barrels, the largest in Africa.

Most of Libya's 6.5m poplation is concentrated along the coast and around the country's oilfields. Population density is about 50 persons per square kilometre along the coast. Inland, where much of the country is covered by inhospitable desert, the population density falls to less than one person per square kilometre.

The head of the Russian-Libyan Business Council, Aram Shegunts, told the Reuters news agency that this investment would be lost: "We have lost Libya completely. Our companies won't be given the green light to work there. If anyone thinks otherwise they are wrong. Our companies will lose everything there because Nato will prevent them from doing their business in Libya."

Whether or not Russia pulls out, Libya has, of course, the vast asset cushion of its sovereign wealth fund, which, although frozen by the UN Security Council, has a large role to play in smoothing the path to stability.

The United Nations Security Council, which had frozen Libya's overseas assets, has agreed to unfreeze $1.5bn for humanitarian needs.

And Italy, for one is moving ahead of the UN's formal "de-frosting" as a pump-primer for government workers' wages and and other essentials.

And a range of new money is also waiting in the wings.

Appetite for Libyan investment pre-conflict was already strong, says Ms Kinninmont:

"An investment conference held last year in London had ready partners for a range of businesses, from property development and tourism to health and education."

She says the opportunities for the country is immense.

"You've got an economy which was totally state-dominated and a state which has just undergone a revolution. It's a pretty interesting position."