Libya oil: The race to turn the taps back on

- Published

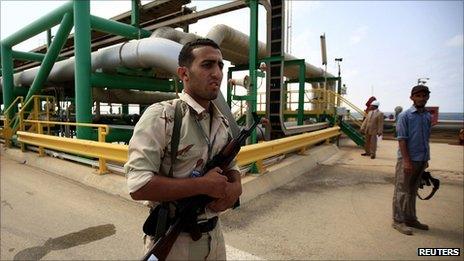

Security is key to bringing Libya's oil production, upon which so much depends, back on line

Libya's long-term prosperity depends on one thing above all others.

Freeing up tens of billions of dollars of frozen assets may be key to the country's short-term reconstruction, but without oil it cannot build a stable economy upon which democracy can flourish.

Libya's oil industry, therefore, holds the key to the success of Libya's fledgling regime and the wealth of its people.

Oil accounts for a quarter of the country's total economic output, and 95% of its export earnings.

But the bloody civil war has reduced Libya's gushing oil fields to a trickle, with production running at little more than 50,000 barrels a day, compared with 1.6 million before hostilities broke out.

As John Hamilton at research group Cross Border Information says: "Libya cannot afford to sit on its sovereign wealth. The bill for rebuilding the country will be enormous, and to meet the vast demands of its population, it has to get oil production up and running again".

Key obstacles

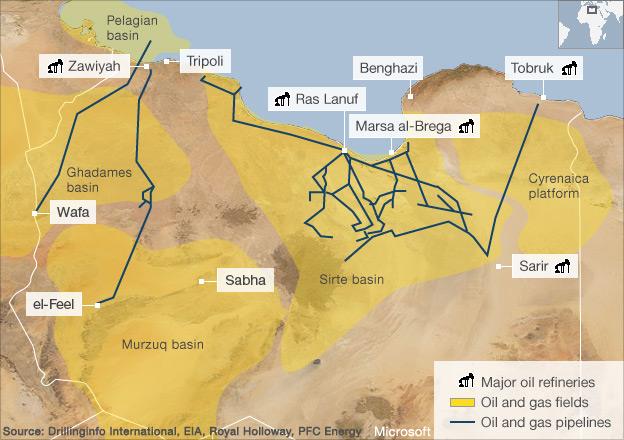

Libya's oil industry relies on three main basins - Sirte, Murzuk and Palagian.

Sirte is the largest and by far the most important, accounting for about 80% of the country's total oil production. It is here in particular where a number of obstacles need to be overcome.

Establishing how much damage has been done to Libya's oil infrastructure is already under way

Security is key among them. Teymur Huseynov, head of energy at specialist intelligence company Exclusive Analysis, says reports that surrounding areas have been heavily mined could delay the return of key personnel.

Depending on the number of mines laid by pro-Gaddafi supporters, and the time it takes to defuse them, work on reinstalling oil production could be delayed by weeks, potentially even months.

Even once the minefields have been made safe, there are important technical issues to address.

A lot of Sirte's pumps are well past their prime and, partly due to what experts refer to as the "waxiness" of the oil, need to be cleaned regularly. The problem is that, because of the war, they have been neglected. There is a chance, therefore, that some may have seized up. In the worst-case scenario, they may even need to be re-drilled, again wasting precious time.

Looting is a further complication, says Mr Hamilton: "A lot of the support infrastructure, such as vehicles and equipment, has been quite badly looted, and this is needed to get back to full production."

The Murzuk and Palagian basins present fewer problems. The oilfields are newer and more secure, although as Mr Huseynov explains, the pipeline from Murzuk to Tripoli has been damaged during the fighting.

Much depends on the extend of the damage - a new pipeline would take at least six months to construct, whereas minor repairs would take a matter of weeks.

Quick return

The uncertainty surrounding these obstacles explains the varying estimates of just how long it will take Libya to return to pre-war production levels.

Energy research company Wood Mackenzie has said it will take three years, while the International Energy Agency and the new chairman of Libya's National Oil Company, Nuri Berruien, both think a return before 2013 is unlikely.

Others are more optimistic. Mr Huseynov thinks 12 months is a realistic possibility, provided hostilities are not reignited.

What is certain is that some oil production, and perhaps a good deal, will begin much more quickly than that.

"As soon as the oilfields are made secure, some pumps can just be switched back on," says Mr Hamilton.

"We could see production at a few hundred thousand barrels [a day] within weeks, with other fields coming online pretty quickly. It becomes incrementally more difficult after that."

Contracts

The sooner production is restored the better, not just for Libya, but for the rest of the world.

Major oil companies are itching to get back in - Italy's ENI, for example, has already returned to assess the damage.

Italian oil group ENI appears well placed to prosper from the reconstruction effort

Libya's new ruling body, the National Transitional Council, has said it will honour all contracts signed with the Gaddafi regime - and the sooner the oil majors return, the sooner they can start generating profits from idle assets.

More interestingly, the new regime will at some point start looking to offer new contracts. An auction scheduled for this year is unlikely to take place, but the likes of ENI, Repsol, Gazprom, Total, China National Petroleum Corporation, BP, and Exxon Mobil are already jostling to be in pole position when the contracts are doled out.

And those that operate in countries that helped the rebels in ousting Muammar Gaddafi could be at an advantage.

Mr Huseynov says that all the normal criteria will be applied, such as technical expertise and quality of labour, but all else being equal, it is these companies that "are likely to get preferential treatment".

On this basis, ENI, Total and BP could steal a march on their rivals.

Global impact

But the rehabilitation of the Libyan oil industry has a wider impact still.

Although it accounts for little more than 2% of global production, Libya sits on a special kind of oil only a handful of countries, such as Nigeria and Azerbaijan, produce.

"Libyan crude is very high quality and the world needs [it]. It's used in transportation, energy production and high-value products," says Mr Huseynov.

He argues that the return of Libyan production to the international oil markets will "put downward pressure on the price of Brent crude, easing inflationary pressure.

"This will be a positive for the global economy."

Indeed, the high oil price has underpinned many of the price rises seen in most economies in the past year.

Not only, then, do Libyans and oil executives have a stake in getting Libya's oil flowing again a quickly as possible - but consumers the world over.