Could Greece be Europe's Lehman Brothers?

- Published

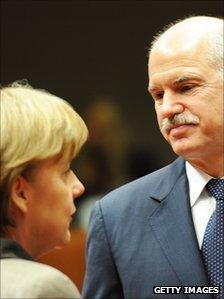

Then and now: Washington thought pulling the plug on Lehman would send the right message; Brussels may face a similar decision over Greece

Three years ago today, US Treasury Secretary Hank Paulson made a momentous decision - to let the investment bank Lehman Brothers fail.

The US government had helped to rescue a string of financial institutions, but markets kept pushing more to the wall.

Mr Paulson was running out of time and options. There was no political support in Washington to keep throwing money at the problem. Wall Street would just have to learn to bear the consequences of its own folly.

Today, many say that it was the wrong decision.

The resulting financial meltdown (the stock market plummeted 43%) forced the authorities to do exactly what they had been trying to avoid - commit trillions of dollars to rescue the financial system.

Plus ca change?

Now fast-forward to the present. The "troika" of lenders to Greece - the European Union, International Monetary Fund (IMF) and European Central Bank (ECB) - may soon face a similar moment of reckoning.

The government in Athens has consistently failed to cut its overspending as much as promised, and keeps coming back for more money.

The Greeks complain that spending cuts demanded by the troika are killing their economy, which in turn pushes their tax revenues down, stoking the need to borrow yet more.

But Germany and other lenders believe southern Europeans have lived beyond their means for years and must learn discipline.

Would they really pull the plug on Greece to make an example of it? Or, with daily protests on the streets of Athens, could Greece itself walk away from the table?

And if so, would it trigger another global meltdown?

Myopic politics

"In both cases, the authorities that could step in to rescue... don't want to commit," says former Bank of England economist Sir John Gieve.

Southern Europe and Germany are playing a game of brinkmanship over bailouts and austerity

Partly this is due to "moral hazard", he says, where rescuing a miscreant bank or government would just encourage more recklessness. Germany has one eye on Italy's half-hearted austerity attempts.

That creates a game of brinkmanship, with each side using the threat of catastrophe to win concessions - austerity versus bailouts.

"It's rational for everyone to take measures to prop the system up," says Sir John. "But because you're doing it on the brink of disaster, there is a risk you don't get your ducks in a row."

The bigger problem is political. The German government recently suffered a huge defeat in regional elections. Greek bailouts are not popular with German voters.

"Politics is not a rational process. Crisis creates myopia," says Jerome Booth, head of research at asset manager Ashmore. He thinks the bigger risk is of Greece pulling out: "All you need is for some politician to stand up and say 'vote for me and you don't have to pay your debts any more'."

Default and devalue

Certainly it would be irrational for Greece to stop playing ball. Cut off from the troika's bailouts, the country cannot borrow.

But even if it stopped paying its debts, Greece would still face enormous pain.

Last year the government borrowed the equivalent of 10.5% of annual economic output, just to fund general government spending.

Would cutting off emergency loans to Greece make a return to the drachma inevitable?

That overspend would have to stop immediately - far worse austerity than the troika demands. The Greek banks would also collapse, bereft of outside support.

Having crossed the Rubicon of unilateral default, many economists believe the Greeks would leave the euro altogether.

One reason is the need to devalue its currency to restore competitiveness. "Greece needs to move its exchange rate by at least 30% to have any chance of getting jobs back," says Mr Booth.

Another is that the Greek central bank could then fund the government's continued borrowing, external with freshly-printed drachmas. But inflation would soar, and imports especially would become very expensive.

Chain reaction

What would this mean for the rest of the world?

In 2008, banks worldwide had borrowed up to the hilt, and were unable to absorb the losses spreading from the US housing market.

That threatened a chain reaction of bankruptcies, which in turn caused a collapse of confidence throughout the financial system.

The resulting electronic bank run was the immediate cause of the meltdown. Banks, brokerages, insurance funds and speculators had relied on a steady supply of cheap, short-term funding, which suddenly vanished.

Banks have spent the past three years slimming down. They also rebuilt their capital, that is, their ability to absorb losses.

Reliance on short-term borrowing has also reduced, and central banks stand ready to provide the emergency loans that rescued the system last time round.

Moreover, this time the surprise factor may be missing.

"[Unlike Greece] Lehman's death throes didn't last two years," points out Sir John Gieve. "Banks have already written down [Greek] debts substantially."

Legal mess

Even so, Europe's banks are still widely seen as the continent's Achilles' heel, with their share prices down 50-70% over the past six months.

European regulators conspicuously side-stepped the possibility of a government debt default when carrying out "stress tests" to check the resilience of banks.

But this has just increased uncertainty about who would suffer most after a default, undermining confidence in all banks.

There is evidence suggesting the European banks themselves, external have already been quietly shifting their cash out of Europe over the summer, while one French bank is now reportedly finding it impossible to borrow in dollars, external.

Mr Booth thinks some banks may not withstand deep losses on Greek government debt, say up to 75% of their original value, and a simultaneous collapse of Greek banks.

And a Greek euro exit would create a huge legal mess: does Greece have the right to leave the euro? Can companies convert contracts in euro into devalued drachmas? How would personal savings and borrowings be converted?

Financial drip

Economists say the greatest damage from a Greek default or euro exit could be from the example it sets, external. Unlike 2008, there is now a second and more worrying channel for financial contagion: government debt.

During the latest jitters, markets have been differentiating more sharply than ever between safe Germany and risky southerners. Why lend to a country that could follow Greece's lead and default, or convert your euro cash into e.g. devalued lira?

The concern at the front of every European leader's mind is that investors may stop lending to Spain and Italy - economies that together are more than ten times the size of Greece.

Already the two have been put on an ECB financial drip.

"There needs to be a clear perception that other countries do not have the same problem [as Greece]," says Mr Booth.

He thinks austerity programmes are going a long way to achieving this distinction.

Growing pains

But other economists warn that austerity worsens a different problem that many southern Europeans share with Greece.

Thanks to rising wages during the boom years, they all have seen their competitiveness versus Germany steadily eroded, but as they are in the eurozone, they cannot restore it by devaluation.

And with Germany insisting that all governments - including itself - slash spending, economic growth is under threat. That in turn makes their debts even harder to repay.

The problem is compounded by the ebbing away of confidence in their banks, making it harder for them to borrow the money needed to support the economy.

Indeed, without German financial support, it may be beyond the means of Italy and Spain, and even France, to rescue their banks while remaining in the euro, undermining confidence further.

Yet the failure of a major European bank would be as unmanageable now as in 2008, and liable to spread the financial crisis across the globe.

Economists say the solutions to the crisis are within Europe's means, external. The problem is the unwillingness of politicians to take the necessary steps because they rankle and lose votes.

So, just as with Lehman Brothers, the big question for markets now is: how big does the financial crisis need to get to create political resolve?

Or will the politicians run out of time first?