The technology of saving India's precious water supply

- Published

WATCH: The last drop: If ground water levels in rural Rajahstan do not improve, these women could be waiting a long time

Surrounded by the rocky Aravalli hills, Rajasthan is one of India's driest states. Despite good rains this year, water has always been an issue here.

But the problem now is that beneath the lush, green, irrigated fields of north-western India, the groundwater is fast disappearing.

In Neemrana, about 150km (95 miles) from Delhi, this has been made worse by human intervention.

Situated on the national highway, this area is part of the industrial development under the Delhi-Mumbai industrial corridor.

The highway is dotted with industries including many water intensive breweries and bottlers.

The state government water board has labelled the district as 'most critical' in terms of ground water, which means the average rate of depletion is more than 0.4m per year.

Irrigating the future

Farmers were first to be affected.

Amar Singh: "Without water, my children and grandchildren have no future on this farm"

Amar Singh's family has been in the business of farming for generations.

His piece of land in Neemrana in Rajasthan is the only source of livelihood for his family.

But as the ground water level decreases, it's becoming harder and harder to get a good yield.

Mr Singh, 65, is worried.

"Water is everything for us. But this is dry land… water is scarce here," he says.

"The water is disappearing so fast that there'll no farmers left. Without water, my children and grandchildren have no future on this farm."

Groundwater is India's lifeline. More than 80% of rural water supply and farm irrigation comes from water sources below the land.

Farmers have been forced to switch to drought-resistant crops like millet

This is water that accumulates in natural cavities and layers of rocks and clay under the ground. This is usually from excess rain water and other surface water that seeps through.

This accumulated water can be just below the surface or deep underground and requires strong motors to pump it up to the surface.

When it rains heavily, these aquifers deep below the ground get fed. The entire area depends on it - leaving farmers reliant on technology to water their crops.

Using sprinkler systems and drip irrigation techniques, the farmers have reduced their consumption of water.

Many here have also switched to more water-efficient crops such as millet and vegetables like garlic, onion, green chillies and okra.

As the sprinklers system comes to life, cool water is sprayed all around Singh's fields. He and his wife check the 1.8m-tall (6ft) millet to see if it is ready for harvest.

Business assistant

Farmers here are getting a helping hand from a local industry that is equally dependent on the resource.

Drip irrigation - using tubes like these - is one way of cutting water consumption

With a brewery in the area, SABMiller India has funded the construction of five water recharge dams. These prevent the excessive run-off of water and help natural water recharge.

Since their construction, the company estimates the local ground water levels have gone up by 17m (56ft).

The company conducted extensive studies in the area to map the water availability. They found that losses through evaporation and run-off are very high in the rocky terrain. Their report showed the shallow aquifer and many community wells were completely dry.

"We have had to spend close to a year in identifying what the shape and form of that structure ought to be," says Meenakshi Sharma, sustainability vice-president for SABMiller.

Meenakshi Sharma at one of the water recharge dams funded by SABMiller

"That has involved the use of satellite data, GPS technology, remote sensing technology and also interactions with the surrounding communities who in their wisdom have noticed the particular points where water doesn't run off but gets percolated down."

But breweries themselves are a water-intensive industry and critics say the company is part of the problem.

"Water is one of the key ingredients of brewing and that's our interest in it," says Ms Sharma.

"Looming scarcity of water in many parts of the world where we are present may actually be a potential business risk for us. In this region... it could be a risk to the livelihoods of small and marginal farmer holders as well."

Water shortage

Two-thirds of Rajasthan is desert and it faces recurring droughts.

Raging thirst: Water is becoming and increasingly scarce commodity in Rajasthan

The government says nearly half the state's ground water zones fall into the "dark" category, where more than 85% of the ground water is developed for use. Many are over-exploited, being 100% developed.

The Neemrana area is categorised as 'most critical' - levels are dropping on average 0.4m per year.

In 2009, a Nasa study said parts of India are on track for severe water shortages.

Nasa's Gravity Recovery and Climate Experiment (GRACE) mission discovered that in the country's north-west, the water table is falling by about 4cm (1.6in) per year.

The scientists said that while they don't know the absolute volume of water in the northern Indian aquifers, they found evidence that the "current rates of water extraction are not sustainable".

Before any group can invest in sustainability programs, they need detailed data about the water balance in the area.

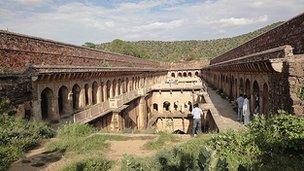

The ancient rulers of Rajasthan used to build step wells like this to store water

So a team of agro-engineers has been employed by the Confederation of Indian Industry (CII). Other than science, they are also relying on ancient knowledge that the region is famous for.

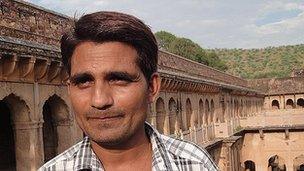

A team led by 33-year-old Vishnu Bhagwat Kelkar studies local step wells in the area.

Historically to combat the scarcity of water, rulers of Rajasthan used to build elaborate step wells or bawaris.

These are structures that store water. But their unique feature is the steps that descend gradually, making access to water easy - even when levels are low.

Mr Kelkar says they study water-bearing formations, look at seasonal changes, monitor different wells in the area and test the water quality.

Vishnu Bhagwat Kelkar is finding out if the ancient step wells have things to teach us

"Once we do that we can map the flow of the water and identify the aquifers. This data helps us determine what is the quantity of water available to the population... and how best to use it."

But these efforts are only a drop in the bucket. With 50% of the villages having no source of protected drinking water, India is a severely water-stressed economy.

And as the scarcity increases, competing demands for water only grow.

The limits to the right to use groundwater were tested recently in the Coca-Cola case in Kerala.

In February 2011, the southern Indian state of Kerala passed a law that will allow people to seek compensation from soft-drink giant Coca-Cola.

Their plant at Plachimada was shut down more than six years ago following a protracted legal battle and a sustained campaign by civil rights groups.

A child waits to fill his water jar from a communal tap

Environmental campaigners had accused the company's bottling operation in Palakkad district of causing a severe water shortage in the area.

Coca-Cola's Indian subsidiary - Hindustan Coca-Cola Beverages (HCCB) - strongly denied any wrongdoing.

At the time, the company in a statement said it was "disappointed" with the new legislation.

"This bill is devoid of facts, scientific data or any input from or consideration given to HCCB," it said.

While scarcity of water is a big reputational risk to companies, it is also a big financial risk to the entire community.

Environmentalists say efficient water management must be supported by stringent laws.

Dr N Janardhana Raju is an environmentalist at the Jawaharlal Nehru University in Delhi.

He says in the corporate and agriculture sectors, there is a need "to prevent over-exploitation and to stop further drilling of bore wells".

"We also have to encourage local communities to harvest rain water. Then only we can maintain ground water levels. If over extraction carries on, there is a risk of land subsidence also.

"Ground water regulation is so weak. That's why we need to revise the regulations and go for much stricter laws."

India is the world's largest groundwater user in terms of volume pumped and number of users.

The government planning commission estimates demand will double by 2050.

Agriculture is still the single biggest consumer of water, with 83% of all water available being used for irrigation. And as this grows so does the 'water footprint' of the entire sector.

Women digging ditches for water storage

This footprint also applies to companies that depend on produce from the fields to make their products.

For example, the Water Footprint Network estimates that the global average water footprint of one 250ml glass of beer (from barley) is about 75 litres.

The group defines the water footprint of a product as the volume of freshwater used to make it through the various steps of the production chain.

People have not given up hope.

Digging trenches along the road, a group of women hope to collect precious drops of rainwater. Fill our pots with water, they pray to the gods.

Water-intensive industries have to work with local communities for effective water management.

But it is only going to get scarcer as the population grows and industrialisation intensifies.

If more is not done to save this precious commodity, both people and industry will be left thirsty.