Q&A: 'Rogue trader' allegations

- Published

Nick Leeson: The archetypal rogue trader

The estimated $2.3bn allegedly dropped by trader Kweku Adoboli at Swiss bank UBS is certainly at the top end of the rogue trading Richter scale.

But it would not be the first occasion, and probably not the last.

How and why does it happen? How is it possible to sweep a billion under the carpet?

What do traders do?

A trader's job at a bank is to buy and sell financial assets, usually using the bank's money.

The purpose of this is primarily what is called "market making" - that is, to provide a buy and sell price to the bank's clients in a particular market - for example, European bank shares, interest rate derivatives or industrial metal futures.

However, some are "proprietary traders". Their role is to make money for the bank by making supposedly intelligent bets on which way the market will go.

There has been a regulatory clampdown on proprietary trading on both sides of the Atlantic since the 2008 financial crisis.

However, in practice it can be hard to distinguish their activity from ordinary market making.

Even a market maker can end up sitting on a lot of unwanted risk if all of their clients choose to sell on a particular day.

And most market makers will use their privileged view of what is happening in their particular market to take bets they are confident will make them money.

Why do traders go rogue?

Normally, traders do not directly profit from their trading activities - unless they seek to embezzle their employer's money.

However, traders do typically receive a bonus that reflects the amount of profit they made for the bank during the course of the year, and this can create an incentive to take reckless bets.

This perverse incentive can become particularly powerful if the trader has already made a bad bet and is sitting on a big, unreported loss.

In this case, a cynical or panicked trader may calculate that either way, if the market does not turn in their favour, the worst that can happen is they will lose their job.

So they may try to conceal the loss, and even to double up their position, in the hope that the market will swing back in their favour before anyone notices.

Are they allowed to take such big risks?

No. Not officially, at least.

Banks require traders to remain within certain risk limits. The trader is required to enter "tickets" logging all of their trades by the end of each day in their bank's internal risk control systems.

Traders who persistently or egregiously break their risk limits can be subject to disciplinary action.

Mr Adoboli worked in UBS' "Delta One" team - the same trading desk that the biggest ever rogue trader, Jerome Kerviel, worked on at Societe Generale, and a business seen as among the larger risk-takers at investment banks.

All trades are also independently confirmed by a "back office" of administrators.

To make a trade, the trader in the "front office" only has to make a phone call or click on a computer screen.

The back office then processes the trade - confirming the transaction with the relevant stock exchange or counterpart, executing any legal documentation and sending or receiving cash and financial securities.

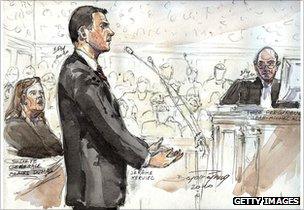

Jerome Kerviel claimed his employer, Societe Generale, knew of his bets, but the court disagreed

If a trader fails to log a trade in the bank's risk control systems, the back office will soon identify the discrepancy, or should do at least.

How do they get round the controls?

There is no simple answer. Every bank has its own computer system and internal procedures.

In the case of Nick Leeson, who famously brought down Barings Bank in 1995, there was no proper separation between front and back office. Mr Leeson was processing the tickets for his own trades.

Jerome Kerviel, the Societe Generale rogue trader, is also supposed to have used his intimate knowledge of the bank's systems from his own time working in the back office.

However, Mr Kerviel claimed that his employer knew about his activity, but turned a blind eye because he was (initially) making big profits - although a French court did not accept this defence.

Mr Adoboli is also said to have previously worked in UBS' back office.

Problems can arise in the over-the-counter market.

This is an informal market that encompasses transactions agreed directly between traders, without going through a stock exchange.

They can agree a legally-binding trade over a recorded telephone line. Documentation is then exchanged between their back offices, formally confirming the exact terms of the trade.

What can banks and regulators do about unauthorised trading?

If they knew that, they presumably would have done it already.

Scrutinising banks' back office and risk control functions more closely is the obvious answer.

After the Kerviel case, the UK's Financial Services Authority came out with a string of recommendations, external for the banks, including watching out for traders with a suspicious number of cancelled trades, and forcing all traders to take two weeks' holiday a year, which would allow others to check their trading books.

Another solution might be to improve traders' incentives - smaller bonuses for success and bigger penalties for misbehaviour.

How does this compare with previous rogue traders?

The $2.3bn figure, now confirmed by UBS, would be near the top of the league table.

SocGen's Jerome Kerviel is in the top spot, having lost 4.9bn euros.

Number two is Yasuo Hamanaka, who lost $2.6bn in metals trading for Sumitomo Corporation in 1996.

Arguably, allowing for inflation, Nick Leeson's $1.4bn in 1995 also pips Mr Adoboli.

Who picks up the bill?

A French court ordered Jerome Kerviel to repay Soc Gen 4.9bn euros, but of course he does not have the money.

So it is the bank itself - or rather its shareholders, via foregone profits and dividends - that typically pays up.

Some of the losses may also be borne by the rogue trader's colleagues, through reduced bonuses.

If the losses are big enough, it can bring down the entire bank - as was the case with Barings Bank - putting the bank's lenders at risk.

But in the case of a giant bank like UBS, a bankruptcy could trigger a financial crisis, so the bank would probably need to be bailed out by its government, putting taxpayers on the hook.

What will this mean for UBS?

The financial loss is manageable - UBS made $6.4bn in profits in the 12 months to June this year, while the investment bank had already accrued a $4bn bonus pool for its star employees.

The Swiss parliament is currently considering tighter regulation of the banks

Far worse may be the reputational damage.

It follows a humiliating rescue and dressing-down by the Swiss authorities after the bank made lost $35bn during the 2008 crisis, and more recently the exposure by the US authorities of UBS' role in providing a tax shelter to US citizens.

Particularly damaging is that Mr Adoboli apparently himself reported the alleged unauthorised trades - which are thought to have gone on for many months - and was never picked up by UBS' internal controls.

All three major ratings agencies have said they are now reviewing UBS' credit rating for a possible downgrade in light of the apparent hole in their risk control systems.

Meanwhile, the FSA and the Swiss regulator, FINMA, have launched a joint investigation into what went wrong, external.

And to cap it all, the Swiss parliament is currently considering legislation imposing tougher regulation on the country's banks.

UBS was already under political pressure in Switzerland to scale back or spin off its investment banking business.

The bank's head, Oswald Gruebel, told a Swiss newspaper on Sunday that he would not resign over the incident.

But this incident will not help UBS' lobbying efforts.

- Published18 September 2011

- Published15 September 2011

- Published6 August 2011