Bangladeshi apparel gains from China’s rising costs

- Published

Western brands such as H&M, Wall Mart, Gap and Next buy their clothes from Bangladesh

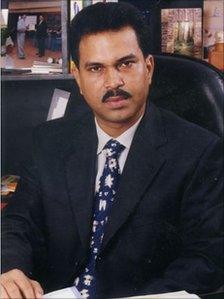

Even after 25 years, Faruque Hassan, still remembers the humiliation and embarrassment he faced when he ventured into garment exports, an unchartered territory in an impoverished country like Bangladesh.

Very few western nations would give him a business visa. On many occasions, he missed out on international trade fairs and key meetings with his western buyers as his visa didn't come through on time.

"Finally, when I went with some samples many western buyers were sceptical," Mr Hassan, who started a garment factory in Dhaka in 1985, told the BBC.

"They wouldn't even meet me. They couldn't believe that a country like Bangladesh can export clothes to rich western nations."

Western brands

Today, Mr Hassan runs nine factories across Bangladesh and clothes made in his factory are exported to Germany, Switzerland, Austria and Canada.

There are more than 4,500 garment factories across Bangladesh employing more than 3.5 million people, most of them women.

Major western brands like H&M, Wall Mart, Gap, Next and Marks and Spencer buy their clothes from Bangladesh.

What started in some humble concrete buildings outside the capital Dhaka has now become the country's key foreign income earner.

Mr Hassan says when he first started he had trouble even getting a visa

In the current fiscal year, Bangladesh exported more than $18bn (£11bn) worth of ready-to-wear clothes, amounting to nearly 80% of the country's overseas sales.

Bangladeshi entrepreneurs say their country has now become the second biggest exporter of ready-made clothes in the world after China.

A recent report by the accounting firm KPMG, external said that, with increasing labour costs, rising inflation and a strengthening currency, China was losing its foothold as the world's lowest cost manufacturer of consumer goods, and countries like Indonesia and Bangladesh had been the biggest winners.

Low wages

The success of the Bangladeshi apparel industry is mainly attributed to its low production costs, in particular its cheap labour.

The average monthly wage for a garment factory worker is about $43, whereas in China it's more than a $100.

"The closest to the Bangladeshi wage is in Cambodia, where garment workers get around $61 per month," says Zahid Hussain a senior economist with the World Bank.

"That's almost 50% more than the Bangladeshi wages. So, the labour advantage for Bangladesh is quite huge."

With a population of more than 150 million, Bangladesh is one of the most densely populated countries in the world.

With most people depending on agriculture for their livelihood, garment factories offer the highest number of jobs in the industrial sector.

The KPMG report said countries such as Bangladesh had an advantage in terms of their young work force.

While the average Chinese citizen is 34 years old, the average Bangladeshi by contrast is almost 10 years younger, and nearly half of the population of the country is of working age.

"In addition to the cheap labour cost, there is no doubt that Bangladesh is also benefitting from various preferential trade agreements," says Golam Moazzem, a senior research fellow at the Centre for Policy Dialogue in Dhaka.

The workforce in the Bangladeshi garment industry is dominated by women

"For example, the EU allowed duty-free access to Bangladeshi clothes in January this year."

The Bangladesh Export Promotion Bureau estimates that at the present level of growth, garment exports would reach $30bn by 2015.

But it says the growth also depends on the impact of the global economic crisis on major western nations.

Child labour

In the early days, for factory owners like Mr Hassan, finding workers was not a problem, but finding skilled and knowledgeable people was a big challenge.

He says factory managers spent hours educating their workers in the basic skills of cutting, stitching and operating sewing machines.

"It's not only the physical training," remembers Mr Hassan. "We had to teach our workers on simple things like how colour matters in dresses.

"In one of our first orders we ended up stitching a large number of pink colour dress for the boys and blue colour frocks for girls."

As Bangladeshi clothes started travelling far and wide, its labour standards also came under closer scrutiny.

The factories were accused of exploiting poor workers to produce cheap clothes, and in some cases using child labour to keep their costs low.

Labour unions say salaries need to increase

In 1995, UNICEF struck a landmark deal with the Bangladesh Garment Manufacturers and Exporters Association to end child labour in the garment factories following international threats to boycott the industry.

By 1998 more than 10,000 children were removed from work under the programme, and nearly 80% of them were enrolled in community-based schools.

Workers' unions say that, despite assurances from factories, working conditions still do not meet those standards in many outlets, especially outside the special export promotion zones.

They say workers are also not happy with the minimum wage announced in late 2010.

"Given the inflation and rising cost of living, it is increasingly difficult for a garment factory worker to survive under the present salary," warns Muhammad Touhidur Rahman, a Bangladeshi union leader.

"If their concerns are not addressed, we can see more labour unrest in the coming years."

The other big challenge for the garment industry is infrastructure bottlenecks.

Road and rail networks have become more congested in the last 20 years, and the country faces a daily shortage of about 2000MW of electricity - almost a third of its requirement.

"We are also worried about the global economic crisis," says Mr Hassan. "Since more than 80% of our exports go to the United States and the European Union, we are entirely dependent on them.

"If the crisis continues there, we will definitely be affected. So, our next challenge is to find new markets in countries like India, Japan and South American countries."

- Published15 September 2011

- Published6 September 2011

- Published6 September 2011