Trying times for Greek families

- Published

Elias Eliadis says he cannot afford to pay Greece's new property tax

A short tram ride along the coast in Athens, Elias Eliadis is playing his guitar in the cramped apartment he shares with his wife Anastasia and grown-up son Apostolos.

He says it's the one thing he does which takes his mind off his daily routine.

He reaches the end of his piece, puts down his guitar, and kisses his wife, who smiles benignly.

Mr Eliadis says he was forced to retire at the age of 48 when he lost his state job in the aviation industry, working for the former Olympic Airways.

He says his pension was fine to start with, but has now been cut by two-thirds. He expects his income to continue falling.

His wife is chronically disabled. The state provides little help and most of what Mr Eliadis receives each month goes on carers.

And he has to support his adult son Apostolos who still lives at home. He doesn't expect to work again.

'Never enough'

"Prices are going up every day," says Elias Eliadis.

"You can't afford to buy whatever you want - you have to look carefully and just get what is necessary.

"There's never any money left over. 1,200 euros ($1,615; £1,039) is a joke - it's just not enough for us all to live on."

Unlike some, Mr Eliadis says he wouldn't choose to defy the authorities and refuse to pay the new property tax - but the question is academic, because he cannot afford it.

"It is not right. This tax in unfair," he says.

"There are so many people in business who never pay taxes and will not pay this one either. They should take the taxes from them.

"I just don't have the money for this. How can I pay?"

The family is worried because the property tax is to be collected via their electricity bills. But it's far from clear whether the government will cut off impoverished citizens who cannot pay.

Moving abroad

Eleni Stamou is now considering moving overseas

Across Athens, in a smarter suburb, recently qualified doctor Eleni Stamou is feeding Greek yogurt to her baby.

She's training to be a radiologist. But she says life is hard in her state hospital - she says when vital equipment breaks there's no money to repair it.

Ms Stamou is the kind of young professional now considering leaving the country if things get worse.

"My salary is already down by 300 euros a month, and we get nothing at Christmas, Easter or for holidays," she says.

"I have to rely on my family for childcare and they provide me with food. We spend much less than we did on clothes and entertainment.

"You just can't save money - it's for living, nothing more. We feel we are working for the banks. We don't want to leave - we like it here, but we are thinking of leaving to work abroad."

One man who has done just that is Jason Manolopoulos, who spends much of his time working as a fund manager in Geneva.

He is the author of Greece's Odious Debt. Mr Manolopoulos says the ruling party's new tax policies are mistaken and no substitute for improving basic tax collection.

"They are going back and asking the people already paying taxes to pay more," he says. "Others still don't pay.

"They are are just trying to milk the same cow more times per day and will just hit a threshold.

"Its unfair because its similar to a poll tax and is levied at a fixed rate regardless of income."

Many fear a run on the banks, causing the country to be forced out of the euro - heralding in turn the return of the drachma.

This would almost inevitably fall in value dramatically against other currencies.

Bank of Greece statistics suggest personal deposits are down about a fifth since 2009.

Mr Manolopoulos says although some of this money has been spent, he thinks a proportion has been sent abroad, and large quantities of euro notes are stashed under mattresses.

'Third world'

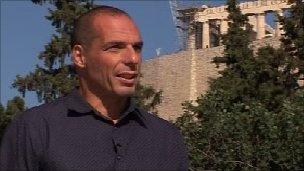

Prof Yanis Varoufakis, head of the Department of Economic Policy at the University of Athens, says that Turkey's experience of 15 years ago provides a stark lesson of what might happen if the country were to leave the euro.

Yanis Varoufakis says the spending cuts are making matters worse

"Those with access to hard currencies would do quite well, thank you," he says.

"But those who only had access drachma would find themselves in a third world situation with very low spending power."

Meanwhile, he says ordinary Greeks find themselves caught in a vicious circle.

"The greater the cuts in the welfare state, health system and employment benefits, the less the economy has the capacity to produce taxes," he says.

"And the less it can do that, the more difficult it becomes to make inroads into the deficit.

"Its a typical debt trap spiral, of the kind we thought we understood well in the 1930s. Greece's plight cannot be solved by more doses of austerity."

So it seems the real cost of the Greek rescue is being born not by banks, but by millions in their every day lives.

Some are protesting on the streets, some are refusing to pay those property taxes.

But most are simply hoping they can hang on and bring in enough to make ends meet in the long wait for economic spring.

More beggars are on the streets, another 30,000 people are to be dismissed from what they once believed were jobs for life.

Wave after wave of tax rises and spending cuts have made life a struggle for millions of Greeks.

The public mood is one of anger, loudly demonstrated by the almost daily street protests.

But behind the scenes, the mood is more one of resignation - born out of constant scrimping and saving to put food on the table when fuel and food prices are going one way and salaries and benefits the other.

In human terms, its not anonymous financial lenders but families bearing the brunt of the austerity measures that Greece's European partners demand after so many years of over-spending and financial mismanagement.

With such a vast debt mountain to climb, and a strong possibility of default or the country even falling out of the euro, the pressure on family budgets is intense.