Do UK banks face another mis-selling scandal?

- Published

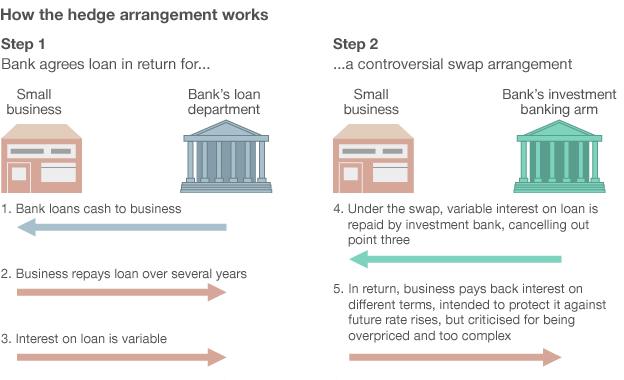

The complaints are not about the loans themselves but rather the "hedges" that came with them

Are Britain's banks on the cusp of another mis-selling scandal?

In April, the big High Street banks were ordered to pay out billions of pound in compensation to borrowers whom they pushed into buying unnecessary payment protection insurance (PPI).

Now accusations are emerging that the banks adopted similar tactics against their business clients.

Loans to small and medium-sized businesses - so-called SMEs - are critical for the UK's economic recovery. So much so, that the government has set lending targets for the banks.

But in recent years some businesses have found that their loans came with an important string attached: banks told borrowers that they must "hedge" their interest rate risk.

Flipside

"This thing is round our neck and bringing us down," says publican Roy Myers.

In 2005, he asked his bank, HSBC, for a mortgage to buy up the freehold on one of three pubs he runs in Redcar, in the north-east of England.

That was back in the halcyon days of the boom, when lenders were mainly worried about rising interest rates.

So the bank told him he would have to take out a hedge with its investment banking unit.

The hedge turned out to be a complicated financial contract known as an "interest rate swap" - something that is normally traded between financial institutions and much bigger corporations.

"We didn't understand it at the time," he says. "They said it was a precaution against interest rates rising. They never looked at the flipside."

As the economy entered recession in 2008-09, the Bank of England slashed interest rates from 5.75% to 0.5%, in order to help out borrowers like Roy.

But with his interest rate fixed by the "hedge", he saw none of the benefit.

And when he asked HSBC to let him repay the remaining £770,000 of his loan, he was told he would have to pay £173,000 to cancel the swap.

From the bank's point of view, the size of the charge is understandable.

After all, the "hedge" requires Mr Myers to pay a much higher interest rate than the bank would be able to relend the money at in the current market.

But the pub-owner complains that his lender never properly explained the risk that he could end up stuck in the hedge, and therefore his loan.

HSBC declined to comment on his case, but told the BBC that it "provides clients with appropriate products according to their needs, knowledge and experience as well as a full explanation of the products and relevant risks".

'Strait-jacket'

Another borrower says that he actually did foresee the risk of being trapped liked this. But his bank (not HSBC or Lloyds) still wouldn't give him any other option.

The businessman - who does not wish to be named because he plans to take legal action against his lender - runs a string of care homes for the elderly.

He needed a loan last year to build new homes, and was told by his bank that he was required to take out a hedge with them.

"We'd never seen anything like it," he says. "It was all like gobbledegook.

"We only wanted to do a proportion - only 75% - so we could still repay some of the loan if we wanted to sell a property in the future."

But the bank insisted he hedge the full amount if he was to receive the loan at all. And - crucially - he didn't have a relationship with any other lender.

He was also told he must hedge for the full 20-year life of the loan, instead of the shorter five-year period he wanted, even though this meant him paying a much higher interest rate.

Now he says, with local authorities cutting back the fees they pay his company for looking after the elderly, the cost of the hedge is strangling his business.

"They put me in a strait-jacket," he says. "All other businesses in our industry are paying much lower interest rates."

It leaves him critically short of cash, and - ironically - at risk of breaching the terms of his loans.

Yet the hedge also leaves him unable to sell off any of his mortgaged properties in order to remedy the situation.

However, he was given little sympathy by Eric Leenders, a spokesman for the British Bankers' Association.

"What the lender is doing, to support their investment, is to make sure that the loan is affordable over the life of the loan," he told the BBC.

"There should be an accountant in a business [of that size]," he added. "If you are running a business of [this size], you should have the competence to understand the principles [of the hedge]."

'Tip of the iceberg'

Just how widespread is this problem?

"We understand tens, and possibly hundreds, of thousands of these products have been sold by High Street banks, mainly in the period 2006 to 2008," says Adam Tudor, litigation specialist at law firm Carter-Ruck.

His firm has received an unprecedented number of complaints from small businesses in recent months, and thinks it may just be the tip of the iceberg.

"It appears that in many instances the banks behaved appallingly when selling these products," he says. "The common feature of the claims is that the bank told the customer all about the benefits but neglected to explain properly the potential dangers."

The Financial Services Authority told the BBC that it believes only some 2,000 such hedging transactions have been sold each year in the UK, and complaints have been low.

"We would expect banks to adequately explain risks and product details to customers," an FSA spokesman said.

But according to Mr Tudor, cases are only now coming to the fore because - with the economy in the doldrums and Bank of England interest rates so low - the cost of these hedges have become unsustainable for many of the businesses they were sold to.

Moreover, some claims have been settled with confidentiality agreements attached, he says.

Small businesses who do not want to shell out big legal fees can turn to the Financial Ombudsman Service (FOS), who from January can compel the banks to pay out compensation of up to £150,000 if they find in the borrower's favour.

However, a spokesman for the FOS said that so far they have not received many complaints.

Profit

Whatever the total number of transactions, the amount of money involved - and the profits made by the banks - could be substantial, according to Abhishek Sachdev.

He spent five years working as a "risk adviser" at Lloyds Bank, selling precisely these hedge products to small and medium-sized businesses that had got into serious financial difficulty, before he quit the bank in July this year.

He and his young colleagues - most of the 50-strong sales team were under 35 - earned hundreds of thousands of pounds in remuneration, pitching the complex products to clients up and down the country on behalf of Lloyds' investment banking unit.

Clients didn't realise how much profit banks were making, says former Lloyds employee Abhishek Sachdev

"Clients would negotiate like crazy on the [loan], but don't realise the bank is making three-to-four times more in profit on the hedging," he says.

"There was no transparency on pricing. We would never, ever disclose how much profit we were making."

The bank would typically charge less sophisticated "retail" clients large margins to generate extra profits, he says.

For example, if the hedge were for a £10m 10-year loan, Lloyds might charge the equivalent of £300,000 profit. Mr Sachdev said other more aggressive banks would charge even more.

This was standard industry practice he claims: "Lloyds were one of the better banks, from my experience in dealing with clients who had come from other banks."

What's worse, the bank locked in the profit from day one of the transaction, claims Mr Sachdev.

That meant that if a client came back only a short while later asking to repay their loan early, they could be charged tens of thousands - the bank's profit - in order to cancel the hedge.

However, Mr Leenders of the BBA said it was up to clients to get the best deal for themselves.

"The price of these products is the price in the market," he said. "Do take professional advice, do take more than one quote, and do take advantage of competing quotes."

Hidden dangers

Mr Sachdev is now a poacher-turned-gamekeeper.

Since quitting Lloyds, he has set up his own firm, Vedanta Hedging, offering advice to businesses on how to avoid getting short-changed by their bank.

"I can price in real-time," he says. "I have access to the same pricing software the banks use.

"When a bank knows that the client is sophisticated and is obtaining independent pricing, they will often reduce the amount of profit they make on the hedge."

He also advises on which hedging product may suit the borrower.

Lenders often show inappropriate and overly complex products that contain hidden dangers, he claims, because it can make the hedge superficially more attractive, while also maximising the bank's own profit.

A spokesman for Lloyds told the BBC that it sold interest rate swaps as hedges to very few of its commercial customers, with 90% preferring to take out a straight fixed interest rate loan.

Only 2% of customers had registered a complaint, the spokesman added.

Mr Sachdev is following in the footsteps of a former colleague, who also blew the whistle, external on his previous career.

So, does Mr Sachdev feel that he personally mis-sold these products in his time at Lloyds?

"I'm comfortable regarding the risk personally from Lloyds," he says, explaining that he always followed regulatory procedures closely - although this did not preclude him from closing very profitable transactions.

And why did he do it?

"I had to," he says. "You had to meet targets if you wanted to get paid, and it was a pressurised culture."