The cost of petrol and oil: How it breaks down

- Published

Only about a third of the cost of petrol at the pumps actually represents the cost of the raw material from which it is made - oil

We all know petrol costs a lot, but how many of us actually know why, and who profits from selling the stuff?

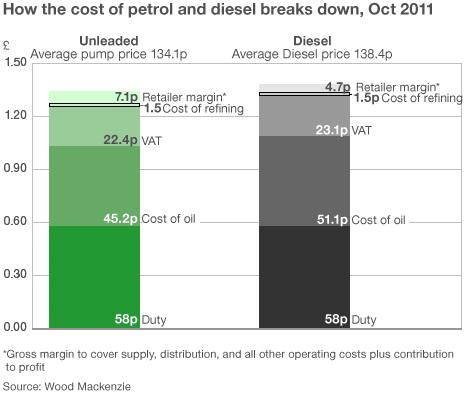

The cost of petrol and diesel can actually be broken down fairly precisely, and it's immediately obvious who the primary beneficiary is: the government.

Well over half, in fact about 60%, of the £1.34 odd we pay for a litre of unleaded is fuel duty and VAT.

Less than 5% goes to the petrol retailer, in some cases more like 1%, which helps in part to explain why so many are struggling despite recent rises in fuel costs.

Next to tax, the single biggest component in the price of petrol is... well, the petrol itself, which accounts for about 30% of the overall cost.

This is what the retailers actually pay for the petrol that comes out of the pumps. This can then be broken down into the cost of oil - the basic material from which petrol is derived - and the cost of refining it into something that powers your car rather than clogs it up.

This refining process actually accounts for very little of the average litre of petrol, so we are left with the cost of oil, which is where things start to get a bit tricky.

Big variation

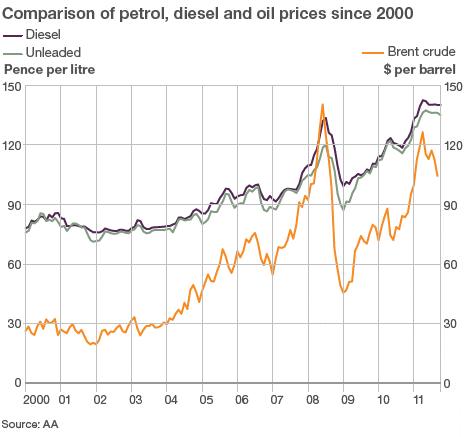

The price of a barrel of oil on the open market is well documented (currently it's about $107 for a barrel of Brent crude), but how this figure is broken down into its component parts is much harder to determine.

Cynics would say this is because vested interests within the oil industry don't want us to know. But delving just a little into the actual cost of producing oil, rather than its price, suggests this view may be a little simplistic.

One of the main reasons for the lack of transparency is simply that there is no standard barrel of oil - the cost of producing one varies massively depending on which of the many thousand oil rigs around the world it comes from.

For example, a bog standard barrel of oil from Saudi Arabia costs about $2-$3 to extract from the ground, whereas a barrel taken from tar sands in Alberta can cost more than $60.

But this in no way represents the cost to oil companies of producing the black stuff.

First they have to find it, which actually accounts for remarkably little of their overall expenditure on production, despite the fact they are having to look further and wider, given dwindling supplies from traditional sources.

For example, setting up a deep water exploration well can cost between $100m and $200m, and only has a one in four chance of success on average, according to Robert Plummer, senior analyst at global energy research group Wood Mackenzie.

Maintaining oil rigs is an expensive business

Then they have to lease the land on which they want to drill, obtain the rights to do so, appraise the reserves they are tapping into, lease the rig and put in place the pipelines and shipping contracts needed to transport the oil for refining.

And this is a lengthy process - typically about seven years from discovery to production.

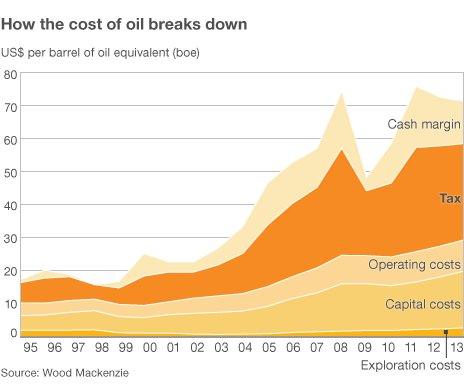

Roughly, this accounts for about 20% of the cost of a barrel of oil, but it's getting ever more expensive as oil runs out and companies are forced to drill deeper in more remote places.

Then of course they have to operate the rigs, which involves maintaining the heavy equipment needed to pump the oil, monitoring and managing reserves, redrilling blocked wells and paying for supplies for crews, who need to be compensated handsomely for the risky work they undertake. This accounts for about 10% of the cost of oil.

This gets us roughly to what a barrel of oil costs to get out of the ground. These figures are based on a proxy cost of oil, which actually includes a not-insignificant weighting for gas. Also bear in mind that these percentages are based on figures for 2011, and they do vary from year to year (see chart below).

Taxing profits

But this is not the cost of oil, for there are two major components missing - tax and the profit the oil companies themselves make. These will account for almost two-thirds of the overall cost of oil in 2011, according to Wood Mackenzie's figures, although it's clear who the biggest recipients are. You guessed it: governments.

Tax on oil is a complicated business - some is charged as a percentage of revenue, while export duties can be onerous - but a good chunk of government revenue comes from taxing the profits of oil companies.

Marginal tax rates on profits in the UK are 62%, more than 80% in Norway and about 90% in some countries. And when profits rise, taxes rise, not just because they are based on a percentage of profits, but also because governments can raise the actual rate of tax itself.

However, even with such high rates of tax, this year oil companies are looking at margins of about 25% of the total cost of oil, which is pretty spectacular by most industries' standards, although this figure does not include financing costs. UK gas and electricity companies, for example, work to margins of about 9%, according to the regulator Ofgem.

But again, these margins vary widely from year to year. For example, in 2009, margins were about 8%, while in 1998, oil companies made no profit at all.

In fact, companies use bumper years to insulate themselves against leaner years, Mr Plummer says.

Finally, then, we have a rough idea of the how the cost of oil breaks down.

Speculation

The margins that oil companies make depend largely on the actual price of oil on the open market.

The difference between the cost of oil and the price of it largely comes down to supply and demand, and speculation by investors. When supply is constrained, such as Libya ceasing production of its high quality oil earlier this year, the price is forced up.

Equally, when demand falls away, for example during the recession that hit most developed economies in 2008, the price falls. More importantly, it is the expectation of future supply and demand that drives the price.

Finally there is the impact of speculators, which is almost impossible to quantify, but many organisations, the motoring group AA among them, believe investors play an increasingly significant role in driving the oil price.

But whether it's speculators, investors, governments or oil companies benefiting from high costs of petrol and oil, one thing is certain - consumers invariably end up losing out.