Poor sanitation stifles economic growth

- Published

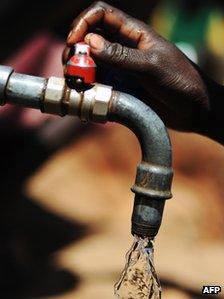

Forty per cent of the world's population has no access to proper sanitation

Two of the Millennium Development Goals, announced at a summit attended by 189 world leaders in May 2000, related to the most basic of human needs: clean water and sanitation.

The objective was to halve, by 2015, the proportion of the world's population who existed without sustainable access to safe drinking water and basic sanitation.

A report released by the UK charity Water Aid, external to correspond with World Toilet Day on 19 November indicates that poor water and sanitation costs Sub-Saharan Africa about 5% of its gross domestic product each year.

That is equivalent to the amount of aid the continent currently receives from Western nations.

Falling behind

With less than four years to the deadline, Dr Zafar Adeel, the chair of UN Water, says the situation is actually worse now than it was in 2000.

"The effort to provide sanitation is not keeping up with the population growth," he says.

In 2006 it was estimated that 2.5bn people had no access to proper sanitation, while figures released in 2008 showed there was an increase of 100m people to 2.6bn.

"The main difficulty has been that many of the governments and funding agencies have not been fully convinced of the value of investing in sanitation as a basic fundamental service," he adds.

"We have been bringing together the policy arguments and the economic arguments to encourage governments to change some of their investment priorities."

Bearing the brunt

Diarrhoea is the biggest child killer in Africa and 88% of those deaths can be attributed to poor sanitation.

Barbara Frost of Water Aid says it is women and girls who are most affected.

"The crisis falls mainly on women and girls because it is them who carry the water and it is the women who look after children who are getting sick with diarrhoeal diseases, often through water infected with faecal material because of poor sanitation," she explains.

Carrying water and looking after sick children means women are unable to earn livelihoods and girls drop out of school when they reach puberty because of inadequate sanitation facilities at school.

Ms Frost emphasises how the Millennium Development Goals (MDG) are heavily dependent on each other to succeed.

"If children do not retain food because of diarrhoea their development is arrested," she says.

"Without proper sanitation you cannot achieve universal primary education, you cannot promote gender equality and empower women, you cannot reduce child mortality."

She is adamant that if health, education and sanitation are looked at as separate issues, people will not get out of poverty because they are so profoundly interlinked.

Hope and despair

The biggest problems are found in Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia, but some countries are addressing the issue.

In the Dhaka suburb of Demra, a man stands in putrid water to collect recyclable plastic

"I have just returned from Uganda where the minister of water is very aware of the link between sanitation and education," Ms Frost says.

"Ministers in other countries have to be reminded to take that link into account when designing schools, and that includes properly designed toilets for disabled children so they are not excluded from education," she says.

Unfortunately not every country is as forward-thinking as Uganda.

"The worse example of poor sanitation I have seen was when I was in Ethiopia in February," Ms Frost says.

"Women were walking five miles from their village to dig in a dry river bed to find water.

"My first sight was a long line of yellow jerry cans and at the end of that line was a big hole and there were women down this hole, standing on each other's shoulders.

"They were collecting water in a cup as it seeped out of the rock because that was where it was cleanest, and handing it up to women on the top to put into jerry cans."

Long haul

Dr Adeel at UN Water says its water programmes have been performing significantly better than those relating to sanitation.

"We are on target to cut the number of people without access to clean drinking water by half in the next five years," he says.

However, at the current rate, the goals for proper sanitation in Sub-Saharan Africa will not be met for 200 years.

But it can be difficult to persuade governments to spend money on sanitation when they are far more concerned in ensuring that families have food on the table.

Ms Frost says sanitation is not at the top of people's minds and it is not a a politically attractive area for investment, while Dr Adeel believes that the assistance and support UN Water has provided could have been on a bigger scale.

"When it comes to human waste," he says, "people should be able to perform that task with dignity and be removed from exposure to it."

- Published20 September 2011

- Published17 September 2010

- Published1 March 2011