How will the euro crisis end?

- Published

European leaders, with the exception of the UK, have backed a tax and budget pact aimed at solving the eurozone debt crisis and preventing the implosion of the single currency. This graphic helps to explain what could unfold next in a crisis that French President Nicolas Sarkozy has warned risks "disintegration" of the eurozone.

- Good economic outcome

- Phoenix from the ashes

- Divorce

- Union

- Euro collapses

- Euro survives

- Unravelling

- Inflation

- Meltdown

- Depression

- Bad economic outcome

- How this graphic works

- INTERACTIVE

-

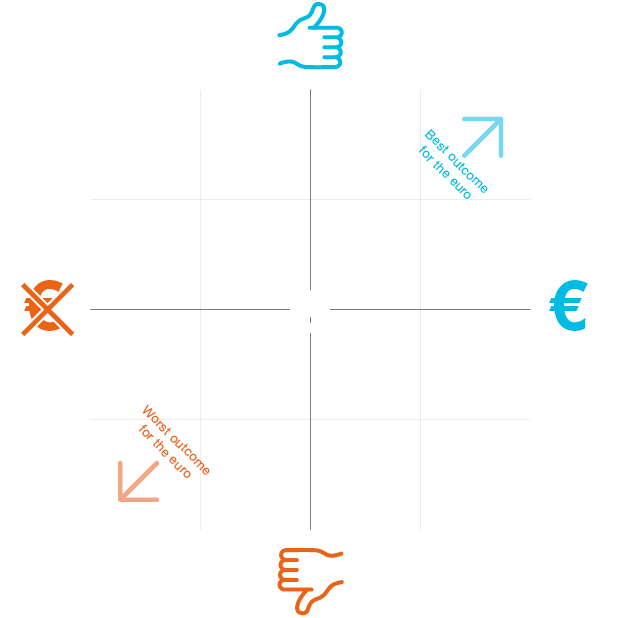

How this graphic works

Click on the black circles to read more about each scenario. Moving from left to right goes from worse to better outcomes for the survival of the euro. Moving from top to bottom goes from not-so-bad to much much worse outcomes for Europe's economy. -

Phoenix from the ashes

The least-bad outcome, where everything goes to plan This is the scenario that Germany and France are hoping for. All eurozone governments agree and stick to the strict new borrowing rules. Italy and Spain get bailouts financed by the European Central Bank. Most importantly, confidence returns. Financial markets are willing to lend to eurozone governments and banks again. In turn, the banks start lending more. Consumers (especially German consumers) start spending again. Businesses start investing again. Europe suffers only a light recession, but then recovers, and slowly but painfully grows its way out of its debt problems. -

Divorce

The eurozone decides break-up is the only option Any solution that might save the euro proves impossible to agree. Irish voters would block any treaty change put to them in a referendum. Along with the southern Europeans, they want to escape the seemingly endless cycle of spending cuts, tax rises, wage freezes and recession. They are angry at the seeming lack of solidarity from the northern Europeans. Meanwhile, voters in Germany, the Netherlands, Finland and elsewhere are incensed by the spectacle of their tax money being used to rescue southern Europeans from the consequences of what they see as laziness and overspending. Governments eventually agree this cannot continue, and negotiate a controlled break-up of the eurozone - perhaps a split into northern and southern European currencies. But this will be hard to do without triggering an "unravelling" scenario. -

Union

The European Union turns into a political federation As the financial malaise keeps doggedly returning, so the eurozone governments call more and more summits and come up with more and more proposals for closer union. Eventually they agree a complete political union - a democratically-elected government in Brussels that can borrow with the backing of all 17 member countries, and can spend money wherever needed - rescuing banks, paying unemployment benefits, financing investment in the more recession-mired countries. The UK and other EU countries not signed up to joining the euro are asked to exit the EU altogether and join a looser free trade area, with much less political influence. -

Who knows?

Anyone who says they know how this will end is deluding themselves If anything is certain about this crisis, it is that nothing is certain. A big bank could suddenly fail. A government could fall, or announce a surprise referendum. Governments or central banks could conjure up a plan that might, just might restore calm (as in 2008). The economic data could turn out much better, or much worse, than expected. Public protests could explode - demanding exit from the euro, or demanding a democratically elected government in Brussels. Leaders could resign or be removed. Everything could be overshadowed by a crisis in an entirely different part of the globe (Russia? China? Iran?). Making predictions is a fool's game. -

Unravelling

The weaker countries drop out one-by-one Fearing exit from the euro, ordinary Greeks empty their bank accounts in droves. The European Central Bank insists that Athens freezes people's accounts, or else it will pull the plug on the Greek banks. The Greek government falls, and its replacement decides enough is enough, announces a stop to all debt payments and a unilateral exit from the euro. The newly reintroduced drachma plunges in value. With widespread anger at spending cuts and recession, there are growing calls in other, bigger, southern European countries, led by Italy's former prime minister, Silvio Berlusconi, to follow Greece's example. That sparks bank runs in the other countries, who in course do end up following Greece. At best a rump eurozone of Germany and France - and possibly Finland, the Netherlands and Austria - is all that remains. There is a risk this could lead to a "meltdown" scenario. -

Inflation

The ECB prints money, prices rise, debts and savings wither away The euro plummets, making the cost of imported goods much more expensive. A strong recovery in the rest of the world pushes up the price of energy, food and raw materials even more. Meanwhile, the European Central Bank prints money to pay for one government or bank bailout after another. The ECB tolerates higher inflation - breaking its mandate - as its bankers secretly believe this is the only way to make the eurozone's enormous debts more repayable. They also want to see wages rise rapidly in Germany, so that workers in struggling southern European countries can regain a competitive edge. But governments continue to spend freely, expecting the ECB to keep lending them newly-printed euros. When a big government breaks the borrowing rules, the rules are simply abandoned. And so the inflation gets out of control. -

Meltdown

2008 again, but without the last-minute bailouts Financial markets lose confidence that the eurozone's problems are solvable. The eurozone's plan - stricter controls on government borrowing - is not credible. Anyway, government borrowing wasn't the real reason the euro got into trouble. It was all the private-sector borrowing that did the real damage. Workable solutions to the economic problems are not politically acceptable. And politically acceptable solutions make no economic sense. Investors stop lending to all eurozone banks and governments alike - except perhaps Germany. Banks collapse. Governments run out of money. Stock markets and the euro plummet. And the politicians run out of ideas and time. The outcome? Think of Russia in the early '90s. -

Depression

The eurozone stays together, but the price is years of economic hell Governments stick to their commitments, and all cut spending at the same time. This causes a deep recession. Consumers and businesses lose confidence in the economic outlook and cut back their own spending, making the recession worse. The European Central Bank cuts rates to zero, but still finds it almost impossible to stimulate the economy. The recession makes it very hard for governments to actually cut their borrowing, because they are spending more on unemployment benefits and earning less in income tax. Companies and mortgage borrowers find it harder to pay their debts, putting the banks in trouble, who cut back their lending even more, undermining the economy further. Eventually borrowers, including governments, have to write off their debts, and many banks and businesses go bust.

You can see more interactive features and graphics here, and follow us on Twitter., external