The year in business: 2011

- Published

2011 was the year when people questioned the creditworthiness of governments

As the editor of World Service business programmes, I have been reviewing the year every December for all but one of the past 20 years.

But never in all that time have the foundations and structures of Western economies looked so shaky.

It is all about debt.

The past decade or so has seen an explosion of the "enjoy now, pay tomorrow" culture in the US and Europe.

Companies, individuals and banks have been addicted to debt. But, up to 2011, there was a general confidence that government debt in the major economies was under control.

The sums appeared to show that the enormous current deficits could be paid off thanks to future growth-boosting tax revenues.

But that gamble - that growth would come to the rescue - does not currently look as if it is paying off.

Instead, economic growth is slowing. Some fear a recession in Europe next year.

Debt mountain

2011 was the year in which everyone started to worry about the creditworthiness of the governments of many of the world's largest economies.

The US lost its top triple-A credit rating from Standard & Poor's - one of the big three rating agencies - but the US president put on a brave face.

"Markets will rise and fall, but this is the United States of America, and no matter what some agency may say, we've always been and always will be a triple-A country," President Barack Obama said.

The US national debt is now $15tn - that is $50,000 for every US citizen.

Across the eurozone, every individual is responsible for $35,000 of their government's debt - and Britain's government debt is not far behind at the equivalent of $30,000 per citizen.

The authorities in Britain and the US have reacted with unprecedented interventions.

Some 20% of UK government debt is now in the hands of Britain's central bank. The US central bank has 15% of America's debt.

In the eurozone, the European Central Bank has been much more cautious, buying up 3% of eurozone government debt.

So how worried should we be?

Investment guru Jim Rogers says the euro in itself is not to blame for the current European debt crisis

Jim Rogers, who co-founded the Quantum Fund in the 1970s and is still a widely followed commentator on global events, says the situation is very serious.

"America is the largest debtor nation in the history of the world, and it's getting bigger and bigger by leaps and bounds at the rate of over $1tn a year," he says.

"If you look at the projections for all the European countries, none of them have reduced debt a year or two or three from now. So this situation is serious and getting worse."

In the mid-1990s, capitalism seemed ascendant, Western capitalism had triumphed over communism, economies were growing, stock markets were growing.

So who does he blame for the fact that we have ended up in this mess?

"Essentially it is governments and central banks, especially in the US. They just kept spending money, and the central bank just kept printing money," Mr Rogers says.

"Other culprits are the government of United Kingdom, the central bank in the United Kingdom, the governments in places like Greece, which used phoney book-keeping, but also even Italy and France and Germany. They all started using phoney book-keeping."

Euro needs to work

"At the moment some governments have credibility - Germany for instance," he says.

"If Chancellor Angela Merkel said: 'You guys are going to fail, you have failed, and now you are going to fail. We are going to hold these banks, these companies up. We are going to make sure they survive' - it would be a terrible two or three-year period, but then the system could survive and we could rebuild after the people who have made mistakes take the losses," he says.

"That's what capitalism is supposed to be all about. If you fail, you fail."

In the early 1990s, Scandinavia had the same problem. They ring-fenced everybody, many people failed, there was horrible pain, but after three or four years Scandinavia has been one of the great growth areas of the past 15 years or so.

In Japan in the early 1990s, they said nobody would fail but they have lost two decades in Japan.

"The Japanese way doesn't work. It is not going to work in America or Europe," Mr Rogers says.

Many people say it is the euro which is at the heart of this crisis. They are calling it the "euro crisis", but Mr Rogers does not see it that way.

"It's not the euro. The world needs the euro or something like it to compete with the US dollar. We need another sound currency. The eurozone as a whole is not a big debtor nation. The eurozone has some debtor problems, some debtor nations, debtor states, but it's not a big, big problem. The euro is good for the world. It needs to work," he asserts.

Banking changes

Since the 1990s, the growth of debt went hand in hand in Europe and America with the growth of so-called universal banks.

The tsunami-crippled Fukushima nuclear power plant caused worldwide concern

These banks combine taking large bets in financial markets - so-called investment banking - with looking after the savings of ordinary citizens and small businesses - so-called retail banks.

During the financial crisis of 2008, the two banks that needed the biggest rescues - Citigroup in the US and Royal Bank of Scotland in the UK - were both universal banks.

Not surprisingly, universal banks are now in the firing line.

In September, a commission set up by the British government, chaired by the economist Sir John Vickers, proposed that universal banks put a protective firewall around their retail businesses to try to stop taxpayers being called on to rescue complex banks in the future.

The Vickers report was criticised by some experts for being too soft on the banks.

Sir John's proposals will still allow one bank holding company - such as Barclays - to own both retail and investment banking operations. But most critics of the universal banks seemed to be happy.

One critic, Michael Lafferty of financial consultants the Lafferty Group, says the reforms will gain further momentum as more countries realise that complex universal banks are not good for any country's economy.

"Banks have become far, far too complex. Many of the world's biggest banks are out of control. Even their top management doesn't quite know exactly what's going on," he says.

"The Vickers' report is really quite an amazing document and does set a very impressive path for the future. Regulators and central bankers around the world are equally impressed," he says.

The recommendations are likely to be adopted around the world.

But what about continental Europe, where universal banks have been dealing with big companies and combining that with depositors and high street branches for many years?

"So-called universal banking they had in continental Europe, typically in countries like Germany, bears no relation to the universal banking that we are talking about existing in the UK and the US," says Mr Lafferty.

"That old-style Germanic universal banking has largely disappeared now. What is now common in the major banks of continental Europe is simply the Anglo-American style of universal banking."

But have politicians and the public in continental Europe focused on this as an issue? Is anything going to change there, because it does not seem to be being talked about that much?

"It is only beginning to be talked about, but my goodness, there will be a lot of talk about it in 2012.

"We are going to see bank collapses, we are going to see a massive banking crisis across several countries in Europe and indeed further afield over the year ahead. Banks are desperately scrambling at the moment to raise additional capital," says Mr Lafferty.

"For example, in the case of Banco Santander in Spain, it needs an amazing 15bn euros of new capital according to the European Banking Authority. Commerzbank in Germany needs something like 5bn. Commerzbank is going to have to turn to the German government for bailouts."

Nuclear retreat

The big story in much of Africa in 2011 was inflation. Annual price rises in Uganda, for example, are now 30%.

The events in the Middle East in the past year were dramatic, but failed to have much impact on the global economic picture, with the very biggest Arab oil and gas producers so far unaffected by revolution.

Probably the most shocking event of 2011 was the earthquake and tsunami that struck north-east Japan in March.

Twenty thousand people were killed. Tokyo - normally one of the world's busiest cities - turned for a while into a ghost town, and supply chains were badly disrupted for firms such as Toyota and Honda.

Perhaps the longest lasting international impact of Japan's disaster will be the global retreat from nuclear power.

Damage to Japan's Fukushima nuclear plant caused significant radiation leaks.

Most dramatically, Germany decided to close its existing nuclear power stations. The energy expert, economist Dieter Helm of Oxford University, says Switzerland and Italy have also recoiled from nuclear, and even in China there has been a rethink after the events at Fukushima.

"What it demonstrated is that, whatever the safety characteristics of nuclear power stations, essentially planning and human error can cause catastrophic consequences," says Dr Helm. "And if we think all the way back to Chernobyl, there was an enormous amount of human error there."

He questions how a sophisticated country could put such a large nuclear facility right on a fault line in such a dangerous geological area.

Coal power

The year 2011 ended with another global conference to try to tackle climate change.

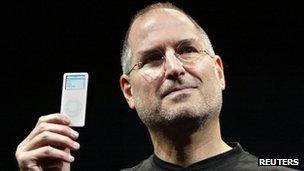

Steve Jobs managed to be a visionary as well as a brutally effective manager

The meeting in Durban called for a new global agreement to cut emissions, but not starting for nine years.

Canada announced immediately that it was withdrawing from the process. Professor Helm says years of talks and the Kyoto Treaty have all failed to do anything effective to cut the carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions that are said by most scientists to be warming the planet.

"The trajectory on CO2 emissions shows very little effect of the global recession so far, and no effect that I can detect from Kyoto whatsoever," he says.

"The reason for that has not been how many wind farms are built in Europe. It has been almost totally explained by the enormous increase in the coal burn at the global level. And if you look at where that coal burn is being concentrated, it has been concentrated in countries like China," he notes.

Looking forward, he believes that a global warming of two degrees would be extraordinarily lucky, but that an additional three or four degrees was more likely.

If economic growth carries on at the current rate in China, it will require up to 1,000 gigawatts of new electricity generation in China.

"That's nearly two coal power stations a week. And to be frank, what the rest of the world does is kind of chicken feed compared with that huge global threat to our climate driven off the back of coal," he adds.

Loss of a visionary

The co-founder of Apple, Steve Jobs, died in 2011. He was an obsessive perfectionist, who made fortunes from products that consumers had not even known that they needed.

The British actor, entertainer and gadget-lover Stephen Fry, explains Steve Jobs's success with technology: "Suddenly computing could be something that was on a human scale: that was visual, that used the human tools that had evolved over millions of years. Our hands, our eyes, our emotions.

"This had never occurred to anybody. They all thought computing was just a thing for nerds, and it was a list of functions that could be performed that would be useful. But for Steve, devices are more than just the sum of their functions."

BBC World Service business editor, Martin Webber, reflects on 2011's financial turmoil and looks ahead to 2012

Once, having a Mac computer was an act of rebellion - a minority cult.

But Leander Kaheny of the Cult of Mac website says the Apple company that Steve Jobs leaves behind is a thoroughly traditional corporation in the way it gets things done.

"There's nothing counter-culture about Apple at all. People have this image of this being a hippy dippy country, but it's not. It's run almost like a Victorian mill. It is extremely disciplined - it hits all of its marks. It has very tight deadlines. Nobody is allowed to talk," he says.

"Its secrecy would put the CIA to shame. It is a very intricate piece of clockwork - you know it works brilliantly, it works beautifully, but it's not necessarily a fun place to work," he adds.

Steve Jobs managed to be a visionary as well as a brutally effective manager.

And, like past titans of the corporate world such as Henry Ford and John Rockefeller, he had an absolute determination to defy conventional wisdom.

- Published27 December 2010