The Wealth Gap - Inequality in Numbers

- Published

Protests have highlighted the inequality debate

Until protestors took to the streets last year, first in New York and then in financial centres across the world, inequality had been a low-key issue.

Not any more.

With the political temperature rising, a stream of new analysis is revealing how sharply inequality has been growing.

In October, the US Congressional Budget Office (CBO) caused a storm by revealing how big a slice of income gains since the late 1970s had gone to the richest 1% of households.

The message was dramatic.

Over the 28 years covered by the CBO study, US incomes had increased overall by 62%, allowing for tax and inflation.

But the lowest paid fifth of Americans had got only a small share of that: their incomes had grown by a modest 18%.

Middle income households were also well below the overall average with gains of just 37%.

And even the majority of America's richest households saw gains of barely above the overall average at 67%.

How does that make sense?

Because the CBO found most of the income gains over the past 30 years had gone to the top 1% of US households. Their incomes had almost quadrupled with rises of 275%.

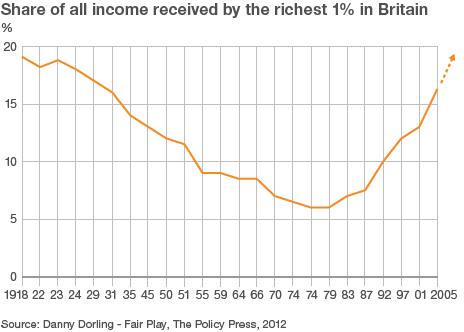

In Britain, Danny Dorling, professor of human geography at Sheffield University, has looked back even further into history. He's charted the share of national income going to the richest 1% since 1918, the end of World War I.

After falling for more than half a century, Prof Dorling says, the share of Britain's richest 1% started rising sharply and inequality is now on course to return to what it was in 1918.

Even within the richest 1%, inequalities are now enormous.

At the lower end of this tiny group of high earners, Prof Dorling says you find people earning £120,000 a year.

But the richest thousand individuals leave them far behind.

They saw their wealth increase on average in 2010 alone by £60m. That was a 20% gain, following 25% the previous year.

In November, the revelation of the size of the increases enjoyed by chief executives of the 100 largest companies on the London Stock Exchange triggered the most political anger.

The High Pay Commission, external reported that these executives' total pay had risen by 49% during the previous year alone, compared with average increases of less than 3% for their employees.

The rise left the chief executives with average pay of £4.2m. That was 145 times the average pay of their employees and 162 times the British average wage.

Responding to the High Pay Commission report, Prime Minister David Cameron this month promised government moves against undeserved high pay awards.

Internationally, vastly more information on incomes is now readily available.

Last year, the Paris School of Economics launched an ambitious project: the World Top Incomes Database, external, providing resources online to allow anyone to examine income inequality.

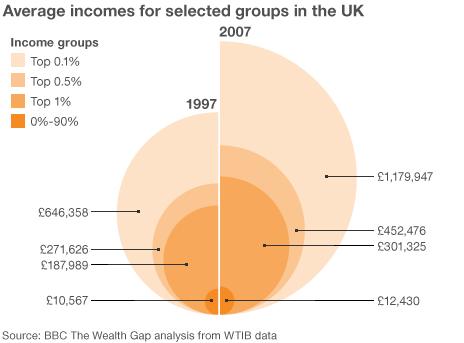

For The Wealth Gap series, we used that data to examine pay at the very top of the British income scale between 1997 and 2007. We then compared that with the average income of the vast majority - represented by the bottom 90%.

This simple analysis reveals striking differences between the rich and most of the rest of the population.

In 1997, the entire bottom 90% had average income of just over £10,500. The top 1% had incomes 18 times bigger.

At the very top - the top 10th of one percent - the multiple was far higher. In 1997, their income was more than 60 times the average of the bottom 90%.

Ten years later, that gap had widened significantly.

By 2007 the average income of the bottom 90% was just under £12,500 a year, but the income of the top tenth of a percent was now 95 times as large, averaging well over £1m a year.

The squeeze on British middle income earners is now regularly analysed by a new independent think tank: the Resolution Foundation.

The Institute for Fiscal Studies offers an online tool, external that allows people in Britain to estimate where they fit on the inequality scale.

It's not just inequality that is now being studied; so are its potential consequences.

In what has become a policymaker's must-read, epidemiologists Richard Wilkinson and Kate Pickett, external claim to have discovered that, across developed countries, the greater the income inequality in any country, the worse the health and social outcomes for everyone: rich and poor.

A widely-watched online lecture on TED Talks, external is spreading this message internationally.

Such analysis has triggered a wide-ranging debate about the broader social and economic consequences of greater income inequality.

Some now argue that it's a cause of financial instability as the international super-rich shift their wealth around the world, increasing volatility in the price of gold, equities, government debt or basic commodities such as copper and grain.

In Britain, the estate agency Savills has charted the inflow of money from the international super-rich into prime London property.

Savills believes this inflow is the key reason why London property prices have gone on rising while the market in much of the rest of Britain is stagnant or falling.

And it's not only the top-of-the-market property that is affected. As price rises at the top of the market ripple across the rest of the city, even first-time buyers earning well above average incomes have found themselves priced out of the market.

Awareness of inequality and its consequences has triggered increased political debate in Britain and elsewhere.

But politicians and policymakers may not find it easy to reverse the trend of the past 30 years.

The first episode of The Wealth Gap was broadcast on BBC World Service on Tuesday 17 January. Click here to listen again.

- Published11 January 2012

- Published8 January 2012

- Published7 January 2012

- Published22 November 2011