Eurozone's Friday the 13th

- Published

- comments

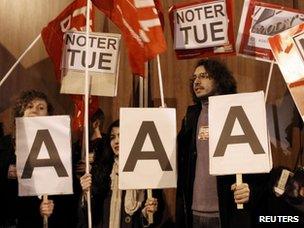

Protesting against the prospect of France losing its AAA credit rating

Even by the recent standards of the eurozone, Friday 13 January has been a messy day.

What may turn out to be most important is that the Greek government moved nearer to a formal default on what it owes, as talks collapsed between the Greek premier, Lucas Papademos, and representatives of banks on a voluntary 50% reduction on what they are repaid.

If there were such a default, that could trigger big losses for banks, eurozone governments and the European Central Bank. It would be the first default by a developed nation in living memory - and would increase the perceived risks of lending to other financially stretched eurozone governments.

So although investors have known for many months that there is a genuine risk of Greece unilaterally reneging on what it owes, there would be a ratcheting up of the currency union's financial crisis, were that to happen.

The second bit of bad news is that the cost for banks of trading in Italian government bonds rose, because an organisation that clears and settles such transactions, LCH.Clearnet, insisted they put up bigger deposits for such deals - which may have the adverse effect of making it more expensive for Italy to borrow.

Finally the event with the most symbolic impact - though not necessarily the greatest economic impact - was the leak that France and Austria are to lose their coveted AAA credit ratings, and other governments, such as Spain, will have their already lower ratings downgraded.

It has been widely expected for some weeks that Standard & Poors would strip France of its AAA, the badge that implies that lending to the French state carries almost no risk.

That said, prominent French bankers warn that as and when that happens, it will become a bit more expensive for French banks to borrow - because all banks are viewed by their creditors as only as strong as the public sector that would stand behind them in a crisis.

For Austria the loss of the AAA will be a bigger shock - although the financial woes of Hungary have conspicuously weakened the finances of Austrian banks that have big Hungarian loans.

But what would really matter about Austria and France losing their AAA is that the downgrade would almost inevitably lead to the loss of the linked AAA held by the eurozone's bailout fund, the European Financial Stability Facility.

And if the bailout fund lost its AAA, it would become much harder and more expensive for the eurozone to raise the funds perceived to be needed to provide possible support to the likes of Italy and Spain, should they be boycotted by investors.

What does it all mean? Well I've talked widely to bankers, regulators and officials today. And frankly they all state what you may see as the bloomin' obvious - which is that the eurozone is a long, long way from being mended.