Can a company live forever?

- Published

In 1288, Stora Enso issued the first share ever granted in a company, giving a bishop an eighth of a copper mountain

The past few years have seen previously unthinkable corporate behemoths - from financial firms such as Lehman Brothers to iconic car manufacturers such as Saab - felled by economic turmoil or by unforgiving customers and tough rivals.

And do not put away the black garb yet - the pace of corporate funerals is set to pick up.

The average lifespan of a company listed in the S&P 500 index of leading US companies has decreased by more than 50 years in the last century, from 67 years in the 1920s to just 15 years today, according to Professor Richard Foster from Yale University.

Today's rate of change "is at a faster pace than ever", he says.

Professor Foster estimates that by 2020, more than three-quarters of the S&P 500 will be companies that we have not heard of yet.

So in a world where former titan General Motors needed a government cash injection to escape bankruptcy and Kodak has had to ask for protection from its creditors, it seems apt to ask: How long can a company survive?

Looking eastward

The implications can be enormous when large companies go under

It is perhaps unsurprising that the country where people live the longest is also home to some of the oldest companies in the world.

In Japan, there are more than 20,000 companies that are more than 100 years old, with a handful that are more than 1,000 years old, according to credit rating agency Tokyo Shoko Research.

The list includes Nissiyama Onsen Keiunkan, a hotel founded in 705, which is thought to be the oldest company in the world.*

There is even a specific word for long-lived companies in Japanese: shinise.

So what is the key to their longevity?

Professor Makoto Kanda, who has studied shinise for decades, says that Japanese companies can survive for so long because they are small, mostly family-run, and because they focus on a central belief or credo that is not tied solely to making a profit.

Local factors could be another key to their success, he says.

Shinise focus primarily on the Japanese market, from Kikkoman's products to small sake manufacturers, and they benefit from a corporate culture that has long avoided the mergers and acquisitions that are common among their Western counterparts.

"Those conditions must be sustained," says Professor Kanda from Meiji Gakuin University. "Otherwise it will be a little bit difficult for them to continue live long."

Predicting the future

But, of course, conditions do change - and what then?

Changing with the times is essential for companies that want to survive for a long time

Although there are exceptions to every rule, the most important factor for survival is an emphasis on innovation and reinvention.

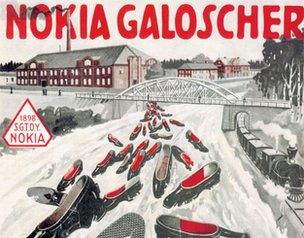

Nokia was a pulp manufacturer before it got into electricity and then mobile phones; at some point its brand name was even used on galoshes. Or take Berkshire Hathaway, which began as a textile mill in Rhode Island.

However, innovation for the sake of it is not the goal, says Vicki TenHaken, a professor of management at Hope College.

It is a focus on "little bets" that helps companies grow and keep up with the competition, she says.

In fact, the world's oldest limited liability corporation, the Finnish paper and pulp manufacturer Stora Enso, first started out as a copper mining company in 1288.

Now the company is looking into expanding into bio-energy and green construction materials, areas that it has spent several years developing.

"The next 40 years look very different from the 700 years behind us," says Stora Enso spokesman Jonas Nordlund, emphasising the company's desire to expand outside Europe in Brazil, China and Uruguay, as well as its investment in cross-laminated timber, a building material that sequesters carbon dioxide.

Balancing act

Research and development may be expensive, but it might help secure long-term survival

Innovation in general is not always easy, however, especially for publicly listed companies that must balance the concerns of capital markets and shareholders, who demand quarterly profits and who are not necessarily interested in decades-long research projects.

"Research and development is always a delicate balance between maintaining a long-term view and remaining sensitive to short-term financial objectives," observes Mark Vergnano, executive vice president at DuPont.

Mr Vergnano cites DuPont's trove of more than 37,000 patents and its early history as a gunpowder manufacturer as proof of its commitment to innovation - but acknowledges that inventions are not enough to keep the company operating from day to day.

DuPont implemented a new rule in 2010 that mandated that 30% of revenue must come from innovations the company has created in the last four years - a move that could help reassure investors who might balk at the company's $2bn research and development budget.

The problems of living forever

Yet even if a company can innovate and conditions do remain favourable, immortality does have its downsides.

For instance, there is no real proof that age makes a company any more profitable than younger companies. On the contrary, evidence from the stock market actually suggests that age could be a hindrance.

When GM filed for bankruptcy, the US government had to come to the rescue to prevent its downfall

Of the 74 or so companies that have stayed in the S&P 500 for more than 40 years, only a dozen or so have managed to beat the average, according to a study by consultancy McKinsey.

In fact, if the S&P 500 were made up of only the companies that were part of the index in 1957, overall performance would have been some 20% worse.

"When a company has run its course it gets bought," says Professor Foster.

"This is a good thing, because if the economy stops changing then productivity would go away.

"All companies would like to think that they're going to be the Methuselah, but they're not."

When to die?

Ms TenHaken agrees, although she also emphasises the toll that unplanned for or sudden deaths can have on surrounding communities - particularly her home of Michigan, which has seen its fair share of corporate funerals.

"I don't know that it's necessary to say that companies should live forever," she says.

"I think the tragedy is that companies die premature deaths. If a company dies too soon we have to ask what went wrong."

As more and more companies look set to take their final bow, the real question for those who are left may not be how to survive, but when to die.

*There is some debate over the oldest company designation. There is an older organisation, Ikenobo Kadokaia, which was founded in Kyoto in 587 AD. However, its stated purpose is the promotion of traditional floral arranging, which is not necessarily commercial in nature.