Kodak: From Brownie and roll film to digital disaster

- Published

The name Kodak has been synonymous with the world of cameras since the firm was founded by George Eastman in the 19th Century.

His vision to keep Kodak at the forefront of photography by the masses has seen its peaks and troughs.

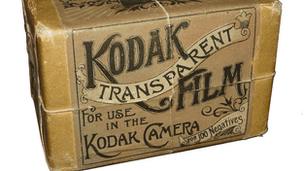

George Eastman saw Kodak take off after pioneering roll film in 1886 - an alternative to cumbersome photographic plates normally only developed by chemists and specialists.

The opaque backing paper allowed roll film to be loaded in daylight. It is typically printed with frame number markings which can be viewed through a small red window at the rear of the camera.

It allowed people to carry around films without their exposure to daylight affecting their use.

$1 camera

Roll film was a major invention for Kodak

As roll film took off, the first model of the Kodak camera appeared. It took round pictures 2.5in (6.35cm) in diameter and carried a roll of film enough for 100 exposures.

Its invention almost single-handedly bought photography to the masses, as before that time both apparatus and processes were too burdensome to classify photography as recreation.

By 1900, Kodak hit the mass market with a new, cheaper camera. Priced at $1, it was intended to be a camera that anyone could afford and use, leading to the popular slogan: "You push the button, we do the rest." An estimated 25 million Brownie versions were sold up until the 1940s.

By 1935, Kodak had invented the first mass-produced colour roll film for cameras, known as Kodachrome. It was initially offered in 16mm format for motion pictures; 35mm slides and 8mm home movies followed in 1936.

Cornered market

As with the Brownie, Kodak cornered the mass market again in the 1960s with the Instamatic. Using the new cartridge film which dropped into the camera without the need to attach to a reel, it was a huge hit. More than 50 million Instamatic cameras were produced between 1963 and 1970.

The cornering of the home photography market by Kodak was reflected in the figures; in 1976, the company sold 90% of the photographic film in the US along with 85% of the cameras.

Although competitors such as AGFA and Nikon have been rivals of Kodak for generations, it was Fuji who gave the firm the biggest headache.

In 1984, Kodak turned down the chance to be the official film for the Los Angeles Olympics, an offer Fuji snapped up without hesitation.

Fuji then took a large piece of the non-digital market in the mid 1990s, when it invented the single-use film camera.

In 1975, Kodak engineer Steven Sasson created what the company describes as the first digital camera, a toaster-size prototype capturing black-and-white images at a resolution of 0.1 megapixels.

Although the technology did not catch on immediately, analysts felt the company's failure to capitalise on this was the start of its decline.

Overtaken by rivals

Former Kodak vice president Don Strickland claims he left the company in 1993 after he failed to get backing from within the company to release a digital camera.

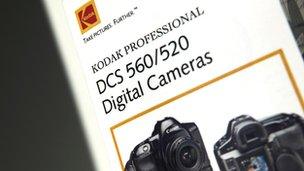

The switch to digital undermined Kodak's reliance on conventional film sales

He said: "We developed the world's first consumer digital camera but we could not get approval to launch or sell it because of fear of the effects on the film market... a huge opportunity missed."

Through the 1990s, Kodak spent $4bn on developing the photo technology inside most mobile phones and digital devices.

But a reluctance to ease its heavy reliance on film allowed rivals like Canon and Sony to rush into the fast-emerging digital arena.

The immensely lucrative analogue business Kodak worried about undermining too soon was virtually erased in a decade by the filmless photography it pioneered.

Chris Cheesman, of Amateur Photographer magazine, said: "We repeatedly questioned why Kodak chose to concentrate its resources on low-end compact cameras and the sharing of digital images.

"No-one wants to be in the low-end compact camera market any more. Other, more profitable, camera makers are gradually pulling away from this market.

"Profit margins are low in the face of increased competition from big electronics manufacturers such as Sony, and the surge of camera phones means consumers can readily share images with less hassle."

Where now?

Kodak's decision to focus on cheaper cameras is seen as a mistake

But what does the future hold for Kodak? If it ceases trading, will the name disappear?

"Kodak played a role in pretty much everyone's life in the 20th Century because it was the company we entrusted our most treasured possession to - our memories," said Robert Burley, a photography professor at Ryerson University in Toronto.

"One of the interesting parts of this bankruptcy story is everyone's saddened by it," he continued.

"There's a kind of emotional connection to Kodak for many people.

"You could find that name inside every American household and, in the last five years, it's disappeared. At the very least, digital technology will transform Kodak from a very big company to a smaller one. I think we all hope it won't mean the end of Kodak because it still has a lot to offer."

- Published19 January 2012

- Published19 January 2012