Tech conversion: India's richest shrine goes green

- Published

Green temple: India's Tirupati Temple has adopted a range of green technologies - and the shrine is now trading carbon credits

Surrounded by seven hills, high above lush green forests is the temple town of Tirumala.

The crown jewel is the dazzling gold-plated temple of Lord Venkateshwara. Located in the southern Indian state of Andhra Pradesh, this is not just one of Hinduism's holiest shrines, but also one of the richest.

It has an annual income of $340m - mostly from donations.

Between 50-100,000 people visit this temple every day. This puts enormous pressure on water, electricity and other energy resources.

Now the temple is using its religious influence and economic might to change the way energy is used here.

Sustainable sources

Developing reserve forests around the temple to act as carbon sinks, the management has transformed the environment.

They are promoting the use of sustainable technologies and hope to influence public opinion.

LV Subramanyam is the executive officer of the temple trust.

"While we currently use a mix of conventional and non-conventional energy sources, our aim is make the place more reliant on sustainable sources of energy," he says

"Most of our devotees are progressive. In a religious place like Tirumala, we can set the example by going green. Probably the impact will be much more than normal government advertisements or publicity."

The community kitchen feeds thousands of pilgrims every day

Inside the temple complex, a large multi-storey building is dedicated to just one thing - cooking free meals for pilgrims.

Several cooks work in tandem stirring large pots of rice, curry and vegetables. Nearly 50,000 kilos of rice along with lentils are cooked here every day.

Open all day, this community kitchen is the biggest green project for the temple.

Located on the roof of this building are rows of solar dishes that automatically move with the angle of the sun, capturing the strong sunlight.

The solar panels on the roof of the temple power solar cookers, powering the community kitchen below

Then the energy is used to convert water into high pressure steam, which cooks the food in the kitchen below.

Generating over 4,000kgs of steam a day at 180º C, this makes the cooking faster and cheaper. As a result, an average of 500 litres of diesel fuel is saved each day.

Credit score

By switching to green technologies, the temple cuts its carbon emissions and earns a carbon offset, or credit, which they can sell.

Badal Shaw is the managing director of Gadhia Solar Energy Systems, which has set up the solar cookers. He estimates that this has resulted in a reduction of more than 1,350kgs of green house gases in the atmosphere.

"This was the first project to get a gold standard certification - it's a registered project and it is issuing carbon credits," he says.

"From a monetary value, carbon being a tradable commodity - the prices keeps going up and down ... we sold the carbon credits of this and various other projects to the German government."

Blowing on the wind

But it's not just the sun that the temple is tapping into. On top of a hill, the site is ideal for harnessing wind energy.

Companies like Suzlon and Enercon have donated turbines which generate a combined total of 7.5 megawatts of power.

The temple also uses electricity generated by wind turbines

A Tirupati-based company called Green Energy Solutions now wants to develop multiple wind farms to supply the entire temple's energy.

Madhu Babu, the founder of the group, says they want to tap into the pool of devotees worldwide, asking them to make a donation of green power to the temple.

The temple is unique because devotees are known to make generous donations of both cash and resources. While some have given diamonds in the past, others have given sheets of gold or bundles of cash.

"We have found that a lot of non-resident Indians are interested in donating sustainable technology instead," says Mr Babu.

Tens of thousands of people, including these two young pilgrims, visit the temple every day

"We want to facilitate such donations and translate them into wind farms, so that the entire temple town can be run on green energy."

Big appetite

India is growing rapidly and is hungry for energy, supplied largely by fossil fuels.

Global consultancy McKinsey predicts that the country's carbon emissions will double in the next decade.

This is why it is more important than ever for India to look at alternative sources of energy, says CB Jagadeeswara Reddy, the local government officer in charge of promoting non-conventional energy development.

The temple city has been identified as a future 'low-carbon footprint city' by European Aid and Development, which works under the European Commission.

But a lot of these technologies cost money and Mr Reddy says it's important to involve the private sector.

"It's important that we make technology accessible for people," he says.

"When pilgrims use the water and learn that sustainable sources of energy are being tapped into make the water, food, power available to them, it inspires them. They too will want to learn more about the technology behind it."

Clean-tech India?

As India is taking steps to limit its emissions, it's also one of the largest producers of carbon credits in the world.

According to a 2010 study by HSBC Research, India's share of the $2.2 trillion market for low carbon goods and services in 2020 could be as much as $135bn.

The report further predicts that India's clean technology market could create 10.5m green jobs, and is likely to grow faster than any other country.

Dr Prodipto Ghosh from The Energy Research Institute says there are already over 2000 companies in the country involved in research and innovation for the low carbon goods and services market.

He says that companies have a financial incentive to use clean development mechanisms, as they monetise projects which otherwise would cost the company a lot more.

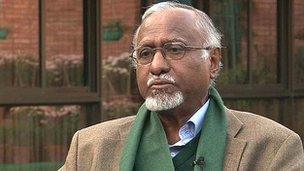

Dr Prodipto Ghosh says carbon credits give companies an incentive to go green

While going green may not make economic sense for everyone, the carbon offsets or credits offer a lucrative incentive to do so. Businesses can exchange, buy or sell carbon credits in international markets at the prevailing market price.

This also is important in relation to the country's energy security.

India now spends 45% of export earnings on energy imports, and this is expected to increase even further.

While the temple assesses the savings that each of these investments can make, the pilgrims enjoy meals cooked using green sources of energy.

To fuel India's growth, there is an increasing demand for alternative sources. Whilst the temple might be one small step, the hope is that this could be a model that is replicated across the country.