Brazil: No longer 'country of the future'

- Published

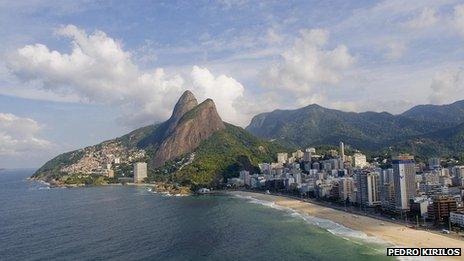

Leblon is one of the wealthiest neighbourhoods in Rio, but a slum is taking over part of the mountainside

The latest economic growth figures from Brazil may not have been as strong as the government had hoped, but the country has still overtaken the UK as the sixth-biggest economy in the world.

South America's largest country is one of the Brics, a group of emerging economies that also includes Russia, India and China, and which together provide a striking contrast to the current gloom prevailing over some of the more established Western powers.

In fact this latest news allows Brazilians a moment of indulgence despite what was actually a year of quite sluggish growth.

In 2011, the country's economy grew by 2.7%, a big drop from the 7.5% growth seen the previous year. Despite its good fortune, Brazil has not entirely escaped the impact of the financial crisis.

However, even with the lower-than-expected result, the old tag of "country of the future - and always will be" is starting to sound less of a joke and more like a promise being fulfilled.

In the last 10 years, Brazil consolidated its role as an agricultural superpower, discovered massive oil reserves in the Atlantic, paid its debts to the International Monetary Fund and developed a more assertive diplomacy.

With a newly-found confidence, it started to break through the stereotypical image when it was often seen by others as only being the land of football and samba.

More and more shopping centres are opening across the country

It also saw the rise of a new middle class, whose purchasing power has been fuelling Brazil's continuous economic growth amid declining industrial output and weak global economic activity.

A combination of economic success and government measures to distribute income has helped lift millions out of poverty, although Brazil remains a very unequal country.

Low unemployment combined with wage increases and a boom in credit has helped to fuel this consumption. The recent growth in the number of shopping centres provides the clearest illustration of this trend.

In 2011, 22 new shopping centres were opened, bringing the total number across the country to 430. A further 74 are planned for this year and next.

'They fished me'

Although interest rates, currently 10.5%, are still among the highest in the world, there is more credit available and current rates are lower than a decade ago.

But the success of the retail sector does not tell the whole story. Investments are also being made in new railways, ports and - more controversially - in hydroelectric power stations. This wave of construction is trying to improve what was widely recognised as the country's deficient infrastructure.

Jose Roberto Miranda says the experience of older workers is valued

At the same time Brazil is starting to face First World realities, such as an increase in illegal immigration and the scarcity of workers in various areas, in what is known as the "labour blackout".

Skilled foreign workers are starting to eye the Brazilian job market, overcoming bureaucratic obstacles to make a fresh start in South America.

"We are starting to receive CVs from Europe and the United States," says Joseph Teperman, a headhunter at Flow Human Capital.

Jose Roberto Miranda is 49 and started a new job at Shell five months ago, thanks to a headhunter.

"I wasn't even looking for a job when they 'fished me'," he says. Ten years ago, someone his age would not have expected this degree of attention.

"Before, someone turning 50 wouldn't have many opportunities. The situation now is different and, with the economy booming, our experience is being valued," he told the BBC.

'Muddling through'

Critics, mainly from within Brazil, say the country was lucky to have China waiting in the wings, hungry for its commodities and natural resources.

China's imports of soya and iron ore do count for most of Brazil's trade surpluses with the Asian giant.

But the so-called "China effect" is also regularly blamed for the fall in industrial output.

In return for soya and iron ore, Brazil gets all sorts of industrialised products, including train tracks made with Brazilian iron.

Business leaders say the South American giant's overvalued currency, the real, and other domestic obstacles such as high taxes and complex labour laws make it hard to compete with an avalanche of cheaper Chinese exports.

"Brazil seems to be muddling through its more serious problems," said Rubens Ricupero, former Economy Minister.

"We are the emerging country that had the highest appreciation of its currency this year. And we are not trying to solve this.

"Our political economy is trying to achieve growth exclusively through consumption and credit. And this leads to current account deficit, as demand will be met with more imports," he told the BBC.

Chinese influence

Even with its domestic market providing an engine of growth, however controversially, Brazil cannot ignore outside conditions. And if a decade ago the US and Europe were the country's main preoccupations, today it is the trends in China that are being watched extremely closely.

As Beijing announced the recent cut of its growth target to 7.5%, big players such as the Brazilian firm Vale, the world's number one iron ore producer, are watching carefully for a decline in demand.

Brazil will soon be hosting the World Cup in 2014 and the Olympics in 2016.

For some, it will be another boost to the country's image, the opportunity to crown the "new Brazil" on the world stage. For others, it will only highlight the difficulties the country still faces.

"The percentage of GDP coming from investments is still low in Brazil and there are serious bottlenecks, not easy to overcome," says Erica Fraga, economic journalist at Folha de S Paulo, the biggest newspaper in Brazil.

"The first big event Brazil will host, the World Cup, will be a test and some say Brazil will fail it. There is a palpable fear among some that the country could collapse."

Wealth gap

In Leblon, a wealthy neighbourhood by the beach in Rio de Janeiro where the presence of hedge funds and the billions they control make its economy comparable to that of a country the size of Uruguay, homeless children are still a common sight.

Brazil's economy has been boosted by the discovery of massive oil reserves in the Atlantic Ocean

Apartments being sold for millions are within walking distance of expanding shanty towns or favelas.

According to the UN, Brazil is one of the most unequal countries in the world.

The government insists it is tackling the problem, mainly through a massive programme of income redistribution, and that inequality has been falling.

Bolsa Familia - Brazil's flagship programme - is now being exported to other developing countries. It is a cash transfer programme that gives families a small guaranteed income if children are kept in school and taken for health checks, and altogether boosts the income of about 50 million people.

Brazilians are well aware that GDP size is not the only economic indicator that matters, and with a population three times bigger than that of the UK, and one of the worst income distributions in the world, there is still a long way to go to reach British standards of living.

But the symbolism of being ahead of an old imperial power whose navy once held sway off the Brazilian coast and which gave the country not just football but helped it build its first railways, banks and basic sanitation does give cause for some quiet satisfaction.

- Published6 March 2012

- Published8 January 2012

- Published6 February 2012