Selecting a new World Bank boss

- Published

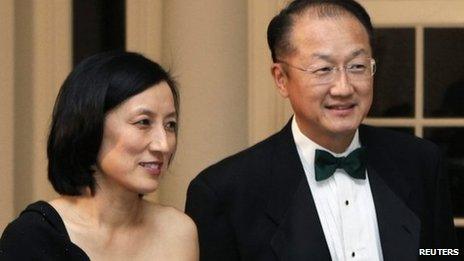

Dr Kim and his wife arriving at a state dinner in Washington

He left it very late. But in the end, President Obama put forward a candidate to take over the World Bank, when Robert Zoellick stands down at the end of June.

The United States' American nominee is Jim Yong Kim, a Korean American.

He is currently president of Dartmouth College, one of the country's most prestigious academic institutions.

His background is in medicine, and he's an expert on health in developing countries.

That's an important area of the World Bank's work. Dr Kim is a former official at the World Health Organisation.

Announcing the nomination, Mr Obama said it's time for the job to be done by "a development professional". The previous incumbents include senior US defence officials and bankers.

What Dr Kim doesn't have is the kind of political profile of Americans who were rumoured to be potential candidates.

Among those were Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, the ambassador to the United Nations Susan Rice and the former Treasury secretary, Lawrence Summers.

Dr Kim, it must be said, is a surprise candidate. A number of news organisations published speculative lists of possible US candidates. Even as it became increasingly apparent that Mrs Clinton had ruled herself out, Dr Kim was on none of the speculative lists that I saw.

Not for a moment does that make him a bad candidate. It just means he will have more work to do to get the World Bank's member governments to know him.

The other options

There are two other candidates, who are not such surprises.

One is Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala, the Nigerian finance minister and a former high level executive at the World Bank.

Where she scores over Dr Kim is her expertise in economic development, which is really what the World Bank is about. In terms of her personal credentials she is undoubtedly a very serious candidate.

There is also the former finance minister of Colombia, Jose Antonio Ocampo. He is currently an academic at - rather confusingly - Columbia University, which is actually in New York.

He, too, has the right kind of experience for a developing country candidate.

He was nominated by Brazil and not by his own government, which is reported to want to concentrate on getting the top job at the International Labour Organization.

But the international political arithmetic is against him and the Nigerian. Here's why.

Selecting the World Bank President is a task for the organisation's board, which is made up of 25 representatives of the member countries. Some of them have their own seats - the US and UK, for example. Others are grouped into constituencies.

The aim is to choose a new president by consensus, but if that proves impossible, a simple majority will do. Votes in the World Bank - and in the IMF too - are weighted by financial contribution.

The US alone has nearly 16% of the vote. European Union countries have a further 29%.

They are likely to support a US nominated candidate, in order to preserve the long-standing informal deal which has seen the World Bank run by an American and the IMF by a European.

Mathematically it wouldn't be impossible to beat an American candidate, but it would be a huge challenge in practice.

If Japan, with 9% of vote, were to get behind the American candidate he would be unbeatable unless the European vote were to split.

It's the first time there has been a formal challenge to the US monopoly on the leadership of the World Bank. Europe however has faced challenges for the top job at the IMF more than once, although they have been unsuccessful.

Increasingly the call is for the posts to be filled by a process that is open, transparent and based on merit.

Of course, the US and Europe have plenty of people perfectly capable of doing these jobs. It's hard to believe however that a selection process that genuinely meets those criteria will not eventually break the pattern that has so far survived more than sixty years.

But the allocation of votes means it probably won't happen yet. That in turn raises another question - whether that system itself should be changed.

There is a reform process on World Bank and IMF governance, as it's called, but it is moving slowly.