Q&A: Apple and e-book prices

- Published

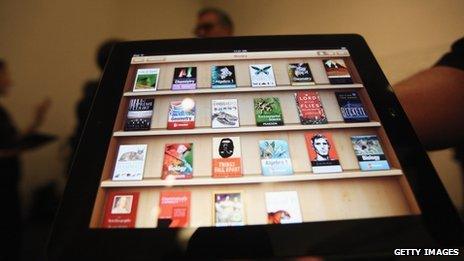

This dispute applies to the prices of e-books on Apple's iBooks platform

Apple is being sued by the US over the pricing of e-books.

Not only that, but five book publishers are accused of colluding with Apple over this - although three have settled with the US department of justice.

So what does this mean for publishers and consumers?

Why has Apple been sued in the first place?

In 2009, Amazon and other online retailers were selling e-books in the US for $9.99 (£6.28) and elsewhere at other simple-to-understand prices.

This is because physical books are sold via the wholesale model - where a fixed price is paid to the seller and the retailer decides how much they want to charge the customer.

At the time, e-books were being sold this way too.

But publishers were not happy with this pricing model because they felt that the cost of e-books was getting too low.

Books were in danger, they argued, of becoming like music had become under iTunes; worth very little.

They wanted to move to the agency model - where publishers set the price of a book and the agent gets a cut.

Apple entered the market in 2010 with its iBooks platform and agreed to the terms of publishers, taking the same cut it takes off apps and music of 30%.

Amazon, faced with the prospect of losing sellers to Apple, soon agreed to adopt the agency model.

The justice department has been investigating whether Apple's decision to side with the publishers is anti-competitive since last year, as has the European Commission on the other side of the pond.

We now know the Americans think it is collusion.

How much should e-books cost?

"E-books should be an awful lot cheaper than printed books," says Tim Coates, founder of e-books sales and lending site Bilbary, and a former managing director at WH Smith and Waterstone's.

"The cost of getting to the first copy is about the same," he says, referring to the costs of finding an author, paying them and editing their work.

"But thereafter, the economics are nil."

Mr Coates estimates that 60% of the cost of a book is down to printing and distribution.

As anyone using any e-book platform such as Amazon, iBooks or Barnes and Noble knows, those savings are not passed on to the consumer at the moment.

But publishers would argue that they do not want books to as devalued as music is now, and as e-books are growing so rapidly, they need the revenue to sustain their industry.

"We make the books, we should set the prices," they say.

Others argue that if you lower the prices, people will buy more.

What will happen next?

With a lawsuit occurring in the US and a competition probe in Europe, it doesn't seem like the e-book market is going to stay the same.

As the terms of the settlement have not been disclosed, it is difficult to know if the three publishers who settled with the US government agreed to abandon the agency model.

Mr Coates thinks that there could be two quite different outcomes, with the US taking a more harsh stand on what Apple and the publishers have done compared with Europe.

"The US has competition written into its constitution, doesn't it?" he says.

France, for example, has had fixed retail prices for books since 1981.

It is often called the Lang Law, after the culture minister of the time, Jack Lang, and states that publishers can set the price of their books and they cannot be discounted by retailers by more than 5%.

Amazon was barred from offering free delivery on books in France in 2007 because of this law, as booksellers said this amounted to an illegal subsidy.

This Lang Law was extended to cover e-books in 2011.

Germany and some Scandinavian nations also have some form of price fixing on their books, so there is the possibility that the Commission will be more tolerant of the agency model.

This could lead to a different set of prices for e-books in Europe and the US, if both authorities come to different conclusions.