Imagination Technologies: A British technology success story

- Published

Graphics on mobile devices are becoming more and more sophisticated

One of the cleverest bits of a smartphone is not designed by whizzkids in California, Tokyo or Shenzhen.

In fact, it is very likely that the graphics technology in your smartphone or tablet PC was developed in Kings Langley, a small town 30 minutes by train from central London.

That's where Imagination Technologies is based.

It is one of Britain's most successful technology companies and you have probably never heard of it.

But look at the screen of a smartphone or a tablet computer and you are very likely to be watching its technology at work.

Imagination Technologies designs the computer chip technology that drives the graphics for mobile devices like the iPhone and tablet computers.

To be clear, it does not make computer chips. Instead, it licenses its designs to companies like Intel and Samsung, who then incorporate Imagination technology into their computer chips.

And then they produce them - in the hundreds of millions. In the business it is called third-party licensing.

It is estimated that 300 million chips that incorporate Imagination's technology are shipped each year, and the British firm makes about 19p ($0.30) on each chip.

Future vision

The market is growing fast.

Hossein Yassaie, the chief executive of Imagination Technologies, told the BBC: "We have stated our goal of a billion units by 2016.

"It is really not difficult to see the volume increase is going to continue (and) penetration in the new markets is going to continue."

As well as graphics for smartphones, Mr Yassaie is confident that his company's other areas of expertise will be in high demand.

That includes connecting devices to the internet and to broadcast systems like radio, and delivering high-definition television to mobile phones.

But, if it is such a profitable, high-growth market, then what has stopped giant chipmakers like Intel and Samsung moving in?

Well, designing graphics chips requires hundreds of extremely skilled engineers with years of experience.

According to analysts, even a giant computer chip firms like Intel would struggle to build a rival team.

The nature of the industry also favours an independent firm that designs the product and then sells it on to everyone else - even to rival firms in the computer chip business.

"The economics of this industry vastly favour the third-party licensing model," says Lee Simpson, a technology analyst at Jefferies International.

"The time to market is a constraint for chipmakers. These guys work on nine-month product cycle, so design lead time is becoming crucial."

Companies that need computer chips, like Apple and Samsung, want new or upgraded products every year, so there's little time to experiment with new designs.

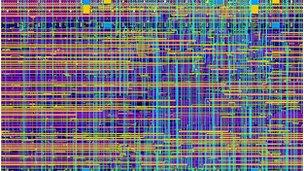

This image gives an idea of the complexity of the graphics processing unit of a computer chip

Customers also appreciate the independence of Imagination.

In fact, so keen are they to stop its technology falling into rival hands that Apple and Intel are the firm's two biggest shareholders.

Strategic masterstroke

So how did a relatively tiny British firm take the lead in such a valuable industry?

When Mr Yassaie joined the firm in 1992, he was convinced that computer graphics was the business to be in.

So the firm developed its technology, and in 1997 landed a high-profile deal to supply the Japanese computer games firm Sega.

But shortly after that came his second strategic masterstroke.

Mr Yassaie decided that people would want to do everything they could do on their personal computers, on their mobile phones.

At the time many considered that impossible, as phones have a feeble power supply and, back then, screens were unsophisticated.

"I was being told by chief executives of other firms that there was no point in targeting the mobile phone market because the screens did not have have enough pixels," said Mister Yassaie.

Fortunately, Imagination's technology was well suited to this task as it required much less power than graphics processors in personal computers.

It quickly found customers for its designs and as demand for smartphones took off, so did Imagination's business.

Imagination also branched out into the radio business. In 2001 it launched the world's first portable digital radio and has been expanding the Pure range ever since.

Imagination has hundreds of engineers working on its products

It has given the Imagination an outlet for its broadcast technology and some valuable experience in dealing with a consumer market - rather than selling to companies.

Big breakthrough?

So what could upset Imagination?

Some analysts are concerned that the company is being distracted from its most profitable market, designing computer chips.

Ian Robertson, a technology analyst at Seymour Pierce, said: "They are taking money out of graphics and investing it into other areas like networking technologies, but it is far from clear if real returns will emerge from those investments."

"I don't see another big breakthrough win like the graphics technology happening again."

Mr Yassaie is confident that is not the case. He thinks his chips are only going to be more important.

He says that in mobile devices, the graphics processing unit (GPU) is doing more and more of the work.

For example, Apple's popular voice command system, Siri, is driven by the GPU.

As for the new areas of business, Mr Yassaie says one should just look at the results.

"Recently we announced a deal with Qualcomm for our Ensigma technology. To get that calibre of a customer surely must suggest we know what we are doing."