IMF: 'Great policies - shame about the economy'

- Published

- comments

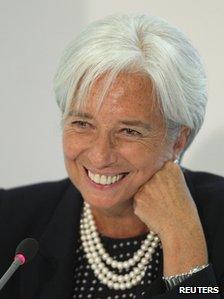

Christine Lagarde does not think things are bad enough for tax cuts yet

"Britain's government is behaving well - it's the blasted economy that's letting everyone down".

That's my translation of the IMF's latest, curious report on the UK, which had some blunt things to say about the state of the economic recovery, and some pointed advice for the Bank of England and the government on how they could make things better.

I say curious, because despite all these misgivings about the economy, the IMF - or its managing director Christine Lagarde, at least - still has only good things to say about the people in charge.

Crucially, for the Chancellor George Osborne, there wasn't much on the fund's to-do list that he hasn't already talked about himself (implementing them is another matter). And the advice that came more from the Ed Balls play list - like the talk of a temporary VAT cut - was still for the future.

In the past 18 months, the IMF has repeatedly said that the government might need to consider fiscal stimulus if "downside risks materialised" and the economy looked set for a prolonged period of slow growth and high unemployment.

For example, in its World Economic Outlook last September, it said: "If activity were to undershoot current expectations, countries that face historically low yields should also consider delaying some of their planned adjustment". It then specified that the countries it was talking about were Germany and the UK.

At that time, the fund was expecting the UK to grow by 1.1% in 2011 and 1.6% in 2012.

We now know that the UK grew by only 0.7% in 2011, and the latest IMF forecast is for growth of 0.8% in 2012 - half what was forecast in September. Since then, most, if not all, of the "downside risks" identified for the UK have materialised and unemployment looks set to remain higher, for longer.

Extra borrowing

However, the IMF's managing director does not think things are bad enough for tax cuts yet.

Why? One answer, which she gave to me in her press conference, is that the government has already loosened policy, in some respects, in response to slower growth. We just don't call it Plan B, because it was incorporated in the government's original framework.

The loosening has come because Mr Osborne has allowed borrowing to go over target as the economy has disappointed - even though the Office for Budget Responsibility told him last November that a good chunk of that extra borrowing might not go away when growth returns.

The extra spending cuts he announced in the Autumn Statement will only kick in after the election. In that sense, the government has "delayed some of the planned adjustment" - though, it must be said, only because the worsened state of the economy means the same amount of spending cuts and tax rises will not do as much to help the public finances in this parliament than they previously hoped. Mr Osborne has not, actually, delayed any cuts.

Another reason not to shift into reverse - according to the fund - is that the government still has other things left in the locker to try. Like serious credit easing, which the Treasury has barely started.

Here the fund was pretty explicit - the Treasury should buy private bonds to help ease the credit constraints on UK businesses (something Mr Osborne and even Chancellor Darling talked about - but has still not happened). It should also exploit the current low cost of government borrowing in support of more private investment.

A tighter squeeze on public sector pay, in exchange for greater investment in public infrastructure, is another thing the fund says the government should try.

'Good friend'

But, you can't help thinking there is a final reason why the IMF managing director held back today - which senior fund officials privately acknowledge.

That is that Madame Lagarde does not want to do anything to make life difficult for her friend George. That is the only conclusion you can draw from her comment, at the end of the press conference - that she "shivered" when she thought of what might have happened to the UK "if no such fiscal consolidation programme had been decided" after May 2010.

I wrote recently about the IMF's own latest research, which said that in countries with spare capacity, "fiscal adjustment implemented gradually has a smaller negative impact on growth than an upfront consolidation of the same overall size.

"This suggests that, where feasible, more gradual fiscal consolidation is likely to prove preferable to an approach that aims at getting it over with quickly."

Ed Balls would say that is what Labour was proposing before May 2010. The IMF was critical of Labour's plans at that time, though not enormously so. (It's noteworthy, looking back, that the UK government's fiscal plans were not singled out for criticism in its World Economic Outlook of April 2010).

We will never know whether Labour's plans after 2010 were "feasible", in the IMF's sense - or would have spooked the financial markets so much that the economy and the public finances would be even weaker than they are now.

But we can say for sure that the chancellor has a good friend in Christine Lagarde.