Pakistan economy at a crossroads

- Published

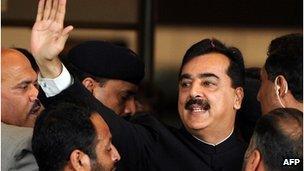

Critics say Prime Minister Yousuf Raza Gilani's administration is crippled by a policy paralysis

Pakistan is a nuclear weapon state with a population of 200 million. Its economic health is of huge significance.

The good news is that its economy is not about to collapse. The bad news is that, without basic reforms, it is likely to be stuck in a slow and steady decline

Last week, Pakistan's economic managers sought to play down worries that the country may be at risk of failing to make debt repayments to the International Monetary Fund.

"We have adequate foreign exchange reserves," declared the governor of the Pakistan's central bank, Yaseen Anwar. "Any decline in reserves will be off-set by expected rise in remittances and foreign investment," he said.

The assurance was part of a damage-control exercise.

Last week, in an interview published in the Wall Street Journal, the governor was quoted as saying that Pakistan's failure to control its budget deficit could force it to return to the IMF for assistance.

Given the perpetually vulnerable state of Pakistan's economy, that is a possibility most analysts do not rule out. But it is quite another matter for a bank governor to openly warn of such a risk.

As expected, his reported comments caused panic in Pakistan's fragile foreign exchange market. Over the next two days, an already weakening Pakistani rupee plunged to a record low.

It came as Pakistan's finance minister, Abdul Hafeez Shaikh, conceded that the economy had missed its target growth rate of 4.2%, and would expand instead by about 3.7% in the current fiscal year ending 30 June.

Figures released last week confirmed that investment was at its lowest in decades, fuelling joblessness and pushing more people into poverty.

All this, at a time when the country is reeling from 11 years of militancy from al al Qaeda and the Taliban, worsening power black-outs and double-digit inflation.

In May, Pakistan's inflation rate reached a 10-month high of 12.29%.

Populist budget?

Analysts say the root-cause of Pakistan's economic ills is a ballooning fiscal deficit, projected to be around 7% of GDP this year.

The government says it aims to reduce the deficit to 4.7%, although many analysts are unclear how the government intends to go about achieving this.

Last week, the government became the first elected administration to survive long enough present its fifth consecutive budget.

Officials described it as an historic day for democracy in Pakistan. But that did not stop critics from decrying the budget as populist and devoid of necessary structural reforms.

It was, they argued, designed to help woo voters ahead of elections expected in six-to-nine months. Taxes were cut, salaries of public sector employees raised, and additional funds allocated for the construction of roads, schools and hospitals.

"The government will be in a hurry to spend much of that money before the polls," says Dr Hafeez Pasha, a leading economist and a former finance minister.

Dr Hafeez Pasha says Pakistan may need more money from the IMF

"One can't say whether these funds will be managed properly and fairly," he said.

The government also announced the creation of 100,000 new jobs in the public sector.

At a time when many of Pakistan's Public Sector Enterprises - such as Pakistan International Airlines and Pakistan Railways - are already struggling for survival due to over-staffing, mismanagement, and political meddling, it's not clear how the government plans to absorb this additional workforce.

"It's the same old approach: political governments trying to take on the role of an employment agency," says Prof Ashfaq Hasan Khan, dean of the National University of Sciences & Technology, in Islamabad.

"Instead, what they should be doing is to frame policies to help create new jobs," he said.

Structural reform

Most analysts agree that the lack of structural reform and poor governance, and an apparent policy paralysis, has hampered the country's economic potential. Pakistan is sometimes referred to as the 'sick man' of South Asia.

"Unless Pakistan changes course and corrects its structural imbalances, we will have to go back to the IMF," says Dr Pasha.

And the sooner the better, he believes. "That way, we'll able to avoid a full blown crisis."

After all, as experts point out, Pakistan's track record in implementing IMF conditions is not particularly good.

The last time the IMF bailed out Pakistan, with $11.3bn (£7.3bn), was in 2008. That programme ended when Prime Minister Yousuf Raza Gilani's government rejected demands for reform and walked out of the arrangement prematurely.

"This time, the conditions are likely to be even tougher and harsher," says Dr Pasha.

"For that reason, I don't see the present government negotiating with the Fund and implementing its conditions before to the elections.

"They appear to be on course to leave a big economic mess behind which the next government will to grapple with," he said.