Will empowered investors curb excessive pay?

- Published

- comments

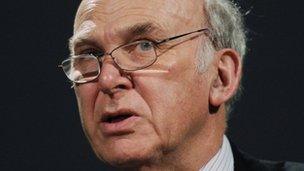

Although Vince Cable may be accused by Labour and some corporate governance campaigners of not being as tough as he could have been with his executive pay reforms, the plans he announces today to give more power to shareholders to curb excessive boardroom rewards will worry many business leaders.

They will make it easier to see precisely how much those who run our biggest companies are actually earning.

And they will force companies to set their policies for three years, with any serious departures from these policies having to be put to another shareholder vote.

The business secretary's main reforms are these:

Every three years companies will have to get authorisation from shareholders via a vote at the annual meeting for how they intend to pay their top executives. The pass rate for the vote would be a simple majority and companies would have to stick to those formulae when allocating rewards until the subsequent vote. In other words, these three-yearly votes would be binding on companies, in contrast to the current system of annual advisory votes.

For the first time, companies will be obliged to publish a simple, single figure in their annual reports, showing how much top executives earned in the previous year. This will include salary, bonuses and any shares that have vested from incentive schemes during the previous 12 months.

The pay policies of companies will have to specify the amounts that would be paid to executives if they were to quit or be sacked. It would be a breach of the law for companies to pay so-called exit payments or golden goodbyes that were more than those pre-authorised amounts.

Robeert Peston: A 12% increase in average pay accross the board... shows that the system is bust

Now, some may accuse Mr Cable of letting companies off the hook by not insisting on an annual, binding vote. However, he would argue that the three-yearly votes should reduce the pace of rises in executive pay, in that the current system of setting pay every year has in practice ratcheted up boardroom rewards far faster than pay has risen in the rest of the economy.

What may also temper executive pay rises is the new simplicity and clarity Mr Cable hopes to bring to the question of how much bosses actually pocket every year. Right now it is very difficult to see the total amount that any executive takes home because the remuneration sections of annual reports are immensely long, complex and woolly, especially in regard to earnings from large and important long-term incentive plans.

What is more, the removal of companies' rights to individually negotiate severance terms could end the perennial scandal of failed executives being paid a fortune when they are being forced out the door.

In theory, the greater transparency in respect of what executives are paid, combined with the new compulsion for companies to stick to pay policies agreed with investors, should change the balance of power between investors and boardrooms, in favour of the owning class and away from the managerial class.

There will be greater responsibility on shareholders to ensure there is a proper link between remuneration and a company's performance, because they should have the tools to do so. If they continue to permit excessive executive pay, it would then be reasonable to be worried that there is a fundamental flaw in our version of stock market capitalism. See my previous blog, the myth of a shareholder spring, for more on this.