Skills key to our cities' survival, history suggests

- Published

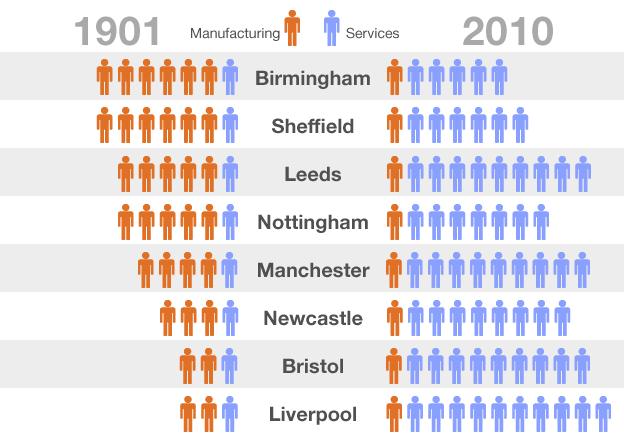

How UK cities have switched from manufacturing to services over the last 110 years

A study of UK urban economies since 1901 has found that investment in skills and infrastructure is crucial to the long-term survival of our post-industrial cities.

The report - <italic>City Outlook 1901</italic> from think tank Centre for Cities - has found that seven out of eight of the best-performing towns and cities today had above-average skills levels in 1901.

Conversely, four-fifths of economically challenged cities in 2012 were in the bottom 20 for skills levels in the year Queen Victoria died.

It also found that investment in infrastructure, such as roads and railways, is crucial to cities' long-term economic success.

Places such as Warrington, Preston, Norwich, and Swindon, have enjoyed the biggest positive change since 1901, says the report, whereas Grimsby, Liverpool, Bradford and Hastings have suffered the biggest reversal of fortune.

Infrastructure

The research shows that short-term cuts in expenditure on education and infrastructure could result in much bigger bills for government in the medium to long term, the think tank argues.

Alexandra Jones, Centre for Cities chief executive, says: "History tells us that failure to invest in city economies has long-term effects for the UK economy.

"The research shows that skills and transport in particular can shape the economic health of a city.

"Ensuring the education system prepares children for the world of work when they leave school is vital for those children and for the future health of the UK economy."

Industrial revolution

The last 110 years has seen a general shift of prosperity and population from north to south, as the UK has moved from manufacturing to service industries in the aftermath of the industrial revolution.

At its height, the port of Liverpool was "the second city of the Empire", said Disraeli

But in 1901, manufacturing, with its reliance on low-skilled workers in textiles, metals and mining, still dominated the landscape.

More than three-quarters of the population lived in towns and cities. Nearly a fifth lived in London, which even then accounted for 20% of gross domestic product, twice that of the entire North West.

Bradford and Hull were in the top 10 of the UK's largest cities, reflecting their importance as industrial manufacturing towns.

As manufacturing declined, their relative importance dwindled, while new transport systems, particularly the railways, brought prosperity and growth to professional service towns in the south, such as Bournemouth.

Thriving ports like Liverpool - once described as "the second city of the Empire" by Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli - ceded power and influence.

By 2011, it was ranked in the 20% worst-performing cities in the UK.

Economic hardship

St. Pancras Station, London, 1900: railways brought prosperity to new towns and cities

Populations in the industrial North and Midlands fell from the 1930s onwards, almost exactly mirrored by a rise in populations in the South East and East.

Even in 1901, Burnley, one of the major Lancashire mill towns, was suffering from post-industrial fall-out, with nearly 13% of its population claiming benefits as a result of economic hardship.

A decade later, the southern town of Southend could boast the UK's highest proportion of people (34.4%) in high-wage occupations.

While old industries declined, unable to cope with global competition, new industries, such as car manufacturing, sprang up.

They successfully exploited technological innovation and put down roots in cities such as Birmingham and Wolverhampton.

Highly-skilled

Cities cannot escape their history, the think-tank argues, nor should they try. Many are inextricably linked with specific industries: Sheffield with steel and cutlery, for example; Stoke with ceramics; Burnley with textiles; Northampton with shoes and boots.

Cambridge University has a strong association with the city's high tech and bio-science industries

And this association has often informed their futures. Sheffield now has an expertise in precision medical instruments, for example.

Cambridge's centuries-long association with its university has contributed to its reputation for highly-skilled technology and bio-sciences companies.

So policymakers and government need to work with the grain of a city's history when planning investment, the authors argue.

Bucking the trend

Some northern towns, such as Preston and Warrington, have managed to buck the macro-economic trend, thanks to investment in roads, railways and new homes, according to the study.

Skilled workers - the key to economic success - were able to move more freely between towns and so help grow formerly struggling local economies.

In short, cities that have adapted best to a changing economy over the last century have been those prepared to invest in skills, infrastructure and enterprise.

Cities rise and fall. But with the right support and investment, this report shows, they can rise again.