US financial reformer is Frank by name, frank by nature

- Published

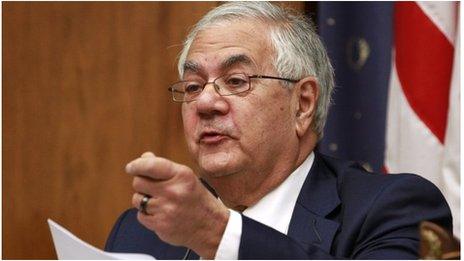

Barney Frank does not always suffer journalists' probing gladly

Answers to the question: "What's your greatest achievement?" often last a good while. Congressman Barney Frank's answer? "I survived," a quote from the French diplomat Talleyrand.

After battling his way through 45 years in US politics, he has emerged as one of its most passionate and feisty characters.

As the chairman of the House Financial Services Committee, he was co-author of the country's post-crisis financial reform, the Dodd-Frank Act.

And he is the most prominent gay politician in the US, proud of fighting discrimination on the grounds of sexual orientation: "I have been both a factor and a beneficiary."

When the next administration takes over in January, he will retire from Congress.

I got a rare chance to talk to him about his career, how the regulation is working and his views on the Libor rate-rigging scandal.

It quickly became clear he is a man of trenchant views - and he doesn't rate journalists very highly.

Ambitious changes

Mr Frank is best known for the act that bears his name, the Financial Reform Act, which runs to hundreds of pages.

Its aims were to strengthen supervision of all financial firms, to make transparent the buying and selling of the sort of derivatives which caused the crash, to protect consumers from greedy predatory lenders and find a way to unwind the biggest financial organisations that come to the brink of collapse.

To say the act was ambitious is perhaps taking the art of understatement to new heights. According to Wall Street law firm Davis Polk, only 120 of the 398 regulations have been finalised and put into effect.

Some of the criticisms lobbed at his regulation are that it is bloated, confused and many-headed. Why is it so unpopular among businesses?

"Because it stops them doing whatever they want to make as much money as they want," he retorts.

"The bill was written because of the irresponsible actions of the financial community, so they don't like what it's doing."

How, then, does he answer the accusation that many of the rules are still not in force, including the Volcker rule, intended to stop banks trading on their own behalf?

He insists the Volcker rule is already on the books, although "the actual regulation isn't there".

Comments from businesses are being scrutinised as part of the legal process, and he predicts the rule will be finalised "within a couple of months".

Grumpy rejoinder

Mr Frank is notoriously, well, frank in his responses. Take, for instance, his answer to being asked about criticism of his regulation from both sides of the aisle - from liberal economist Joseph Stiglitz, who thought it didn't go far enough, and Republicans, who thought it went too far.

"I have to comment," he says waspishly, "you are true to your profession as a journalist. Apparently in your studies, you have found no-one who thinks the bill does anything right."

He grumpily reminds me there was a third group of people who thought Dodd-Frank got it right: "It's very popular with the public."

James Ready and Barney Frank's July wedding left little room for Libor worries

What about criticism that financial innovation has been stymied or slowed down by the red tape of the act? "To the extent that AIG was selling credit default swaps it couldn't stand behind," he says, "thank God we slowed them down."

As a man who has squared up to the biggest and most powerful bankers on the planet, Mr Frank is clearly horrified by the latest banking scandal, the rigging by Barclays traders of the Libor interest rate, which measures lending rates between banks.

He says he was really shocked by "the conscious manipulation of what was supposed to be a neutral, very important measuring rod".

He says the case undermined a major argument used against the Dodd-Frank Act that self-regulation for banks should be encouraged.

Libor, he says, was "a classic example of the government entities delegating to the private sector actors the ability to do things. They seem to have totally abused that privilege."

Marriage first

It turns out Mr Frank had not been concentrating on the Libor scandal in its early days.

He had a very good reason: "I was about to get married, so Libor was not at the top of my personal agenda." He got married in a ceremony in Massachusetts to his long-time partner, James Ready.

Now, though, he is itching to investigate the Libor affair. "I've spoken to my staff and we're ready to get deeply involved," he says.

On the question of how you can change such bad behaviour, he says the Libor case may be an example of instances where individuals need to be punished: "One way to change behaviour is to penalise people who consciously and deliberately violate the law."

The obvious question is, should people go to jail for rigging Libor? He fends it off, saying: "It's way too early to say."

On the wider issue of what's happening in the US economy, Barney Frank brushes away concern that it is slipping back toward crisis, with the US presidential election in just a few months.

"I don't think we face anything as bad as we did in 2007, 2008," he maintains.

He feels there is a silver lining from the crisis - that previously, countries trying to curry favour with businesses had competed to deregulate and under-regulate. "That's basically over now."

And the future? "That was a terrible blow we were struck," he admits, "but I am optimistic, especially if we recognise it is no longer appropriate for us to be the world's policeman."

Mr Frank, ever the liberal, wants to see massive cuts in military spending to attack the US fiscal deficit. Will he miss the political battles?

Maybe, he concedes, "but I intend to be in the intellectual battles, just not in the marching parades."