What's gone wrong with the banks?

- Published

London's financial district is governed by new rules these days

Former City correspondent and current BBC presenter Peter Day here looks back at how London's financial centre has changed since he first started covering the City in the 1970s.

The City of London has changed beyond recognition.

Not just the way it looks and the space it occupies - it now includes the Docklands - but also the way it behaves.

When I started bicycling round the City in 1975, the Bank of England insisted that all banks in London's financial district had to be within 10 minutes' walking distance of the governor's office.

This was done, it was said, so that in times of crisis he could summon bosses of the banks to his parlour with half an hour's notice.

Thus the governor could rule the City merely by raising his eyebrows, in that celebrated phrase, face to face.

Bank governance was done deftly, behind the scenes.

The governor never spoke in public, thus preserving his mystery.

<bold>Changing ethos</bold>

Being able to walk to the Bank of England used to be essential for London's financiers

It was only in the 1980s, when the Bank relaxed that 10-minute rule, that it was possible for Canary Wharf to become a permissible place to base London banks.

And with Big Bang in October 1986, everything changed.

Overnight, the old London Stock Exchange monopoly of the gentlemanly partnership brokers and jobbers was officially abolished.

The brokers sold out to incoming hordes of banks.

The move created the equivalent, it was said, of 1,500 millionaires as the partners sold their interests to the bankers and retired to their country rectories.

The ethos of the City of London was changing rapidly, giving new powers to the regulators, as opposed to the all-seeing eyes of the Bank's governor.

<bold>Universal banking</bold>

The City of London flourished as thousands of new jobs sprouted on the new dealing floors and financial services became a boom industry.

Canary Wharf's newly erected towers became not overspill back offices, but vital contributors to the economy.

There was no room in the old Mediaeval City for many buildings with sufficient floor space for the huge, open-plan dealing rooms that were never needed in the old partnership days.

Foreign banks flocked to the City, and Britain's banks felt they had to participate in the rush into universal banking that became evident all around.

They had, after all, been huge.

Midland Bank was the biggest bank in the world for decades, but a conventional one, with millions of retail customers and thousands of business clients served by hundreds of local branches.

Upside only

A major new problem was the cultural gap between the natural caution of the trained banker and the huge appetite for risk of the new breed of traders created by the influx into investment banking.

For generations, the High Street banks were on the whole run by traditional bankers brought up through the ranks, who had no gut feeling for what the traders were doing and may not have understood it.

Often the overall bosses, chairmen and chief general managers, as chief executives of banks used to be called, were paid far less than the bonus boys on the trading floor.

Bonuses were another curiosity of the new City of London.

In the old partnership world, profits were divvied up at the end of the financial year, as the partners shared the rewards of their stewardship. In bad years no payouts, in good years bonanzas.

The post-Big Bang City in the 1980s replicated this reward structure in order to motivate its adrenaline-fired staffers, but without the downside.

They shared only in the putative profits.

Animal spirits

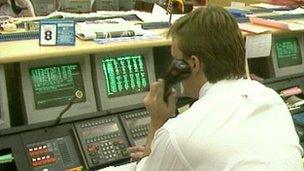

A new breed of City boys took over during the 1980s

Back at the Bank of England, that old regime of regulation by gubernatorial nods and winks could no longer function in the post-Big Bang world, when so many of the participants were international players who did not respect or even understand familiar, gentlemanly City concepts such as the Stock Exchange motto My Word is My Bond.

As a great participant in the burgeoning global financial markets, London needed regulation, not the self-governance of a kind that had ruled the City for 200 or 300 years.

Enter the official regulators with their rule books. Enter the compliance officers with their rule-based authority. Enter the lawyers and accountants, billing clients by the six minutes for both keeping within the rules and seeking loopholes to exploit.

The really significant change in the City of London and its banks and other institutions is the change from the cultural ethical norms of the 1960s and 70s to the post-Big Bang regulated environment.

What regulation tends to do is to define the things that are regulated and create enormous opportunities for the unregulated.

Hence the use of so-called "off-balance sheet entities", that got US banks into such trouble in the sub-prime mortgage crisis, saw tremendous growth because they were outside the purview of the authorities.

Where regulators draw clear lines, the animal spirits of free market capitalists will seek to side-step the line or operate outside the regulations. And they will be hugely rewarded for doing it.

Short-term gains

So in participants' minds, doing "what is right" was replaced by doing what is OK by the lawyers and the compliance officers: Doing what you can get away with, you might call it.

Now, it would be foolish to mourn too much the vanishing of the old City of London.

It was snobby and introverted and uncompetitive and full of restrictive practices, and as such very unhealthy.

But it has been replaced by something even more disquieting: a system where short-term gains are king, and anything else is relegated to a sideshow.