Olympic success: How much does a gold medal cost?

- Published

The Great British team is on course for its best performance since the first London Olympics in 1908

How much does an Olympic gold medal cost? With a minimum six grams of gold and a large chunk of silver, the pithy answer is about £450.

But as Britain basks in the glory of what is shaping up to be the most triumphant Olympics for Team GB in more than 100 years, it is worth reflecting for a moment on the reasons behind the success.

Talent, punishing training regimes, pride in a home games and fervent support have of course played a key part in so many record-breaking performances.

But, in the end, as cynical and unpalatable as it may sound, the main reason behind the team's overall success is cold, hard cash.

Medal bonanza

In the Atlanta Games in 1996, the British team won a grand total of one gold medal, and 15 in all.

The following year, National Lottery funding was injected directly into elite Olympic sports for the first time.

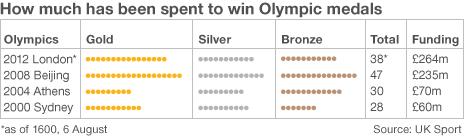

The return was instant. In the Sydney Games of 2000, the British team won 11 golds - the first time Britain won more than 10 golds since the Antwerp Games in 1920 - and 28 medals in total.

Athens in 2004 saw a similar return, the last games before the Olympic Committee awarded the 2012 games to London.

Investment in Olympic sports in the UK immediately rocketed in preparation for the country's first games since 1948, and again the return was both immediate and spectacular - the British team won 19 golds and 47 medals in total in Beijing in 2008.

"When Great Britain went to Beijing, the team benefited from £235m investment in training programmes in the years running up to the Olympics - that's a fourfold increase on what was spent [in the run up to Athens]," says Prof David Forrest, a sports economist at the University of Salford.

"We spent an extra £165m and got 17 more medals, so that's about £10m a medal."

'Big impact'

This massive increase in investment in elite sports was funded in large part by the National Lottery.

"Lottery funding in the 90s has a lot to do with [Great Britain's recent success]," says Stefan Szymanski, professor of sports management at the University of Michigan.

"That devotion of financial resources, particularly on building up elite teams, has had a big effect on Britain."

More successful sports such as cycling receive greater funding, making them even more successful

In fact, the Lottery accounts for about 60% of funding for GB's Olympic teams' preparation for the London Games. Almost 40% comes directly from the UK exchequer - in other words, directly from our pockets via taxes.

This equates to about 80p a year per UK taxpayer. About £7m also comes from money raised by Team 2012, mainly through corporate sponsors.

Just how big an impact all this money has had becomes even clearer when you look at individual sports.

In Beijing, the most successful sports were those that received the most funding. Between them, athletics, cycling, rowing, sailing and swimming accounted for half of all Olympic team funding. They also accounted for 36 of the 47 medals won.

The same pattern can be seen in the current Olympics - almost half of all funding went to these five sports and, so far, together they have won 27 out the 40 medals won.

Of course, there is a chicken and egg element here, as funding is rewarded on the basis of success.

Once the pattern in established, however, it is hard to break, as the more successful sports get more money, allowing them to become even more successful.

Closed sports

In fact, there are some sports that are in effect closed to all but the most wealthy nations.

"We have identified four sports where there is virtually no chance that anyone from a poor country can win a medal - equestrian, sailing, cycling and swimming," says Prof Forrest.

He points to a study suggesting there is one swimming pool for every six million people in Ethiopia.

Wrestling, judo, weightlifting and gymnastics, he says, tend to be the best sports for developing nations.

For the majority of other disciplines, money is key.

According to Prof Szymanski, 15% of all Olympic medals ever awarded have been won by the US, with European countries accounting for 60%.

"These are two very rich and relatively highly populated regions. The combination of these two is probably what goes to producing Olympic medals over the long term," he says.

'Real difference'

Australians are certainly starting to question the role of money in their team's relatively poor performances in London - at the time of writing, the country is lying 24th in the medals table, with just one gold.

Kevan Gosper, Australian member of the International Olympic Committee, can see one very obvious reason.

"We've been down on the sort of financial support that we were accustomed to when compared with the financial support that's coming through from other countries, particularly here in Europe," he told Australia's ABC radio during an interview from London.

"That really cost us... the money is the difference between silver and gold."

For other countries, it's the difference between finishing on the podium and finishing nowhere.

"If you start thinking of [the games] in terms of 'how has my country performed relative to others', then you can get rather cynical, because the shape of the medals table is driven mainly by just how rich a country is," says Prof Forrest.

But with Team GB's haul so far costing each UK taxpayer less than 10p a medal, you won't find too many Britons complaining. Add in a conservative £12bn cost of hosting the games at £400 per taxpayer, and some may not feel quite the same.

*Tennis is funded by the Lawn Tennis Association