The European Coal and Steel Community turns 60

- Published

The European Coal and Steel Community Flag has not been raised since July 2002

The European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC) is 60 years old today.

And whether you wish it a very happy birthday or wish it had been strangled at birth is a pretty good sign of how europhile or eurosceptic you are.

That is because the ECSC was the forerunner of the European Union (EU).

How and why it was set up tells us a lot about the EU and why it operates the way it does.

The ECSC was a French idea, normally credited to the country's foreign minister Robert Schuman, although his advisor Jean Monnet was the real force behind it.

This is why there are so many Jean Monnet roads, buildings and chairs of European studies across the continent.

The idea was to bring together the coal and steel industries of Europe, remove barriers to trade between them and govern them by an international body outside direct national control.

The hope was to make another World War impossible by taking control of coal and steel - the products needed to make weapons - away from national governments.

And by tying the economies of Europe so closely together, war would look like an increasingly ridiculous choice. Shared economic growth, the architects behind the idea hoped, would replace military confrontation.

UK refusal

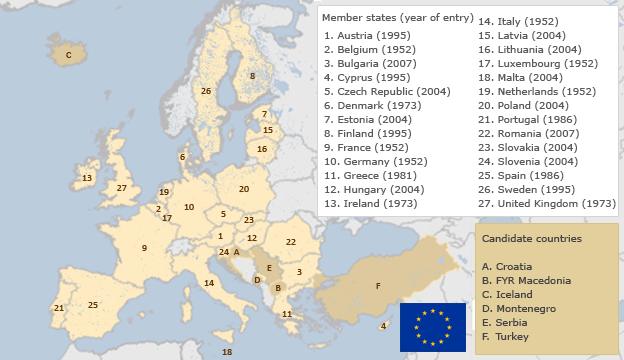

The first six members were France, West Germany, Italy, Belgium, The Netherlands and Luxembourg, the same original six that went on to form the Common Market.

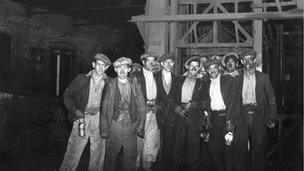

The UK refused to have anything to do with the idea with the now famous put-down: "The Durham miners won't wear it."

That was uttered by Herbert Morrison, the deputy prime minister, who was tracked down by his civil servants having dinner at The Ivy restaurant in London.

If that makes you think some things never change, Herbert Morrison was the grandfather of Peter Mandelson, who went on to be a European Commissioner in Brussels.

The UK opposed the ECSC, insisting "the Durham miners won't wear it"

But in-between those two events there has been a lot of history.

The European Coal and Steel Community was always seen by those who planned it as just a first step in a process of ever closer integration.

It spawned Euroatom, which did much the same for the nuclear power industry and led to the Common Market in 1958.

Once again, the UK refused to have anything to do with the idea, though in 1973 it changed.

That, of course, was far from the end of the matter and there has been a long line of summits, treaties and name changes that have led to what is now called the European Union.

Long lasting

At its most integrated these days, the European Union has no passport controls between states in the Schengen Area and a single currency covers the eurozone - all in the name of closer economic integration and ever closer union.

But the real legacy of the ECSC was to set the framework for how the EU would work, including a supranational authority running it day-to-day and an international court that outranked national law.

That authority is now the much-derided European Commission, although the never ending sequence of summits in Brussels shows that the national politicians managed to get back in the game as well, while it is the equally controversial European Court of Justice that decides who is breaking European law.

The ECSC lasted until 2002, by which time all its functions and powers had long been absorbed by the EU.

But at least it outlasted the last Durham coal pit by almost a decade.