Man Utd: Why football stock market flotations will not make a comeback

- Published

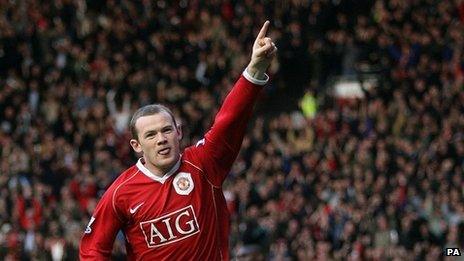

Players' pay shot up as ever more clubs raised money on the stock market, but investors often suffered massive losses

The owners of Manchester United, the Glazer family, have sold 10% of the shares in the club to investors in the USA, raising about £150m in the process.

It has been a long time since the owners of a football club in the UK sought to raise funds by selling shares in the club to professional investors or the general public.

The idea was pioneered by Tottenham back in 1983 and for quite a while the club was seen as a distinct oddity.

The idea of indulging in a stock market flotation was then copied by the owners of Manchester United in 1991.

Then, with hundreds of millions of pounds (later to become billions) starting to flood into English football, courtesy of the new Premier League and its TV deal with BSkyB, joining the stock market became the fashionable thing to do.

Glen Hoddle was still Spurs' star player when the club floated on the stock market in 1983

There was a rush to cash in on the new prosperity of football and to use the stock market as a route to fresh funds, to develop the supposed commercial opportunities that were opening up for the clubs.

By the end of the 1990s, more than 20 clubs had taken this route to fund raising.

But the fact is, it is an idea whose time has come and gone.

Prune juice economics

The one-time owner of Tottenham, Sir Alan Sugar, long ago explained in his typically blunt fashion just what was wrong - and still is wrong - with the finances of football.

He described it as an industry that was ruled by "prune juice economics".

By that, he meant the money went in at one end and then came straight out of the other end, mainly in the form of ever more extravagant salaries for players and huge payments to their agents.

As a result, the past 20 years or so of unprecedented income for clubs, especially in England, has bypassed any ordinary investor who sought to make money out of it.

Clubs, even in the Premier League, have been perennially loss-making as they have thrown ever larger sums of money at players, in a seemingly uncontrollable effort to stave off relegation.

All the while they have, collectively, been racking up massive debts.

And, over the past two decades, this has proved too much of a burden.

In that time more than half of all Premier League and Football League clubs in England have been declared insolvent at one stage or another.

Very few listed clubs paid a dividend and their share prices slumped.

No wonder that a football club investment fund, launched in 2007 by the bank Singer & Friedlander to cash in on the new craze, was effectively wound up five years later, after initial investors had lost more than 40% of their money.

New rich owners

The past few years have seen most of the biggest and (potentially) wealthiest clubs being bought up by very rich foreigners who think they have the funds to subsidise a top class, or even second class, football club.

The Glazer family will sell hardly any voting rights, despite selling 10% of the shares

The result is that today, only two football clubs in the UK still have shares quoted on the stock market - Celtic and Arsenal.

In the case of Arsenal the shares are not readily tradeable as they are mostly owned by a few very rich individuals.

Geoff Walters, of the Birkbeck Sport Business Centre, part of the University of London, says all this shows one simple thing: being on the stock market is fundamentally incompatible with being a football club.

"Ordinary businesses will focus on profit, that will be a key motivating factor driving their behaviour," he points out.

"But football clubs have to balance financial performance with on-pitch performance, and when there are huge increases in revenues, then a lot of that money is spent on player wages, who are the key aspect which helps clubs achieve their performance on the pitch.

"That means clubs fail to make profits and that makes it very difficult to give dividends and for their shares to increase in value."

Potential profit?

While some of Manchester United's 1991 flotation went to private owners such as Martin Edwards, some was also used to fund ground development at the Old Trafford stadium.

The Glazers will use the proceeds of their 10% share sale to pay off some of the club's accumulated debt, and to give themselves a hefty payment.

But the key thing to realise is that the Glazers are not simply copying their club's own history.

They have no intention of letting anyone else begin to have a say in how the club is run, which would be the natural consequence of opening up the share register to new investors.

The owners of the new Manchester United shares will be awarded only a tiny fraction of the shareholders' overall voting rights.

And they have been told that dividend payments are unlikely too.

Their only real economic prospect is that the club becomes even more successful in the future and that the value of the shares rises as a consequence, to give them a potential profit if they chose to sell later on.

The Glazers' latest move may be classed as a stock market flotation.

But it is a very different one to those seen in the past.