UK jobs: The plot thickens

- Published

- comments

Analysts are still looking for a definitive reason why employment is rising while the economy shrinks

Here's the statistic that Britain's finest economic brains simply cannot explain: the number of people in work in the UK has risen by 201,000 in the three months to June, a period in which our national output is supposed to have shrunk, by 0.7%.

It's good news that there are more people in work, and that unemployment has fallen by 46,000 in those months as well. But it's not necessarily good news that collectively, as a nation, we seem to be needing to hire a lot more people, to make less stuff.

I have discussed this many times before, because it's a puzzle that has been with us for a long time (see, for example, this article from June 2011).

You might ask why it's so important to get to the bottom of this. If there's one part of the economy that's producing some good news - why not just sit back, and enjoy the novelty? The trouble is that the longer the puzzle continues, the more potentially worrying it becomes, because it becomes less and less likely that simple measurement error explains it.

It is quite possible that the economy is stronger than the official statistics suggest: in fact, we already know that construction and industrial output were stronger in June than the ONS expected when they came up with their first estimate for the change in GDP in the second quarter. Other things equal, that could see them revise up their numbers later this month, to show the economy shrinking by 0.5%, instead of 0.7%.

But that's a pretty small revision. Even if the extra Bank Holiday also pulled down the numbers temporarily, we'd still be looking at a flat economy, which somehow produced more than 200,000 jobs.

And, to state the obvious, it's not just the past few months that needs explaining. The latest figures suggest there were 501,000 more people in work in the UK in the second quarter of 2012 than there were two years earlier, when our economy is supposed to have been slightly larger than it is now.

To get rid of that longer term mystery, the ONS would have to decide that everything it had said about GDP in the past two years was wildly wrong -that instead of being flat, we actually grew by more than 2%.

That is possible. But implausible, even to those - like the Bank of England - who believe the ONS does tend to understate growth. You don't find that amount of missing output behind the sofa.

Of course, there is the other possible explanation, that the jobs figures are actually worse than they look. It is true that about a quarter of the rise in private sector employment in the past two years has been part-time work. Today we saw the number of people reporting they were in part-time work because they couldn't get a full-time job reach another record high.

More than 1 in 4 of the new private sector jobs created in that time were self-employed. Here at the BBC we have interviewed many self-employed people in recent months, including for tonight's piece for the television bulletins. Many say they are barely working at all - certainly a lot less than they would like. There are some who look and feel like budding entrepreneurs. But quite a lot of them would not describe themselves in this way at all.

Still, that leaves a roughly 280,000 increase in the number of people working full-time for a private sector employer during the past two years, when the economy has been weak, at best.

Pay may be part of it: today's figures show average earnings are still not keeping up with inflation. Wages for most workers have been falling, in real terms, for several years. That has made it easier for companies to keep people on or hire more workers to do the same job. But again, it can't be the whole story.

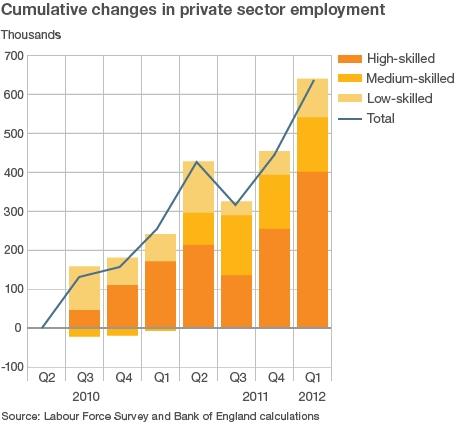

Some say the simplest explanation is also the right one. There is no puzzle. We're just a lot less productive than we were before the crisis, because we've ended up shrinking our highly productive sectors, and expanding our less productive ones. But, as the Bank of England points out in its latest Inflation Report, the figures don't really support this explanation either. About two-thirds of the increase in private sector employment has been in high-skilled occupations.

Another common explanation is that companies have been "hoarding" staff, taking a hit during the slump for fear of not being able to re-hire good people when the economy picks up. But the latest figures don't really back that up either: figures from the Labour Force Survey don't show any fall in the number of people leaving their jobs, relative to the years before the crunch. Quite the contrary.

Finally we're left with the explanation favoured by Britain's finest economic detectives at the moment (not to mention senior policy makers): it's a mixture of all of these possible factors, plus, maybe "something else".

That's a pretty unsatisfying conclusion. If it were the last page of a detective novel, you'd be asking for your money back. But this isn't a novel. Economic mysteries usually get solved, eventually, you just have to "let the data run long enough". That's economist-speak for waiting to see what happens.

We know that the Olympics and other one-offs have distorted the recent figures: London accounts for nearly half the rise in employment. In Yorkshire, Midlands and Northern Ireland - unemployment actually went up last month.

Many analysts think the rest of the country will also see unemployment tick up again in the next few months: the latest private surveys of employers have been pretty gloomy. But the curious case of the UK labour market that wouldn't quit is likely to keep Britain's economic minds enthralled for some time to come.