China banks under pressure as loans turn sour

- Published

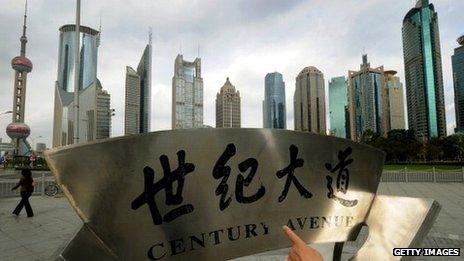

The view of the Pudong financial district in Shanghai, home to a stock exchange and many leading banks

As European and US banks have stumbled from bail-out to scandal in recent years, China's four biggest lenders have basked in the glow of unprecedented profit growth.

But the latest earnings reports from the country's banks, due by the end of August, are likely to show that the days of making easy money are numbered.

Economic growth in China this year is forecast to slide to its lowest since 1999, stoking fears of losses from bad loans as struggling companies and local governments delay or stop repayments.

Reported rates of non-performing loans (NPLs) are still low, running at around 1% of all bank loans, but the figure is expected to rise.

There are also concerns that banks are slow to categorise questionable loans and others go unreported, leading some analysts to conclude that a debt crisis looms.

"There was a huge explosion in lending over the past few years and so much money was going out so quickly...it's more than likely the credit quality went out the window," says Patrick Chovanec, an associate professor of business at Tsinghua University in Beijing.

"I don't think the NPL figures capture the risk to the economy."

Weak note

Bank of China, the first to release earnings, set a weak tone for the rest of the "Big Four" - Industrial and Commercial Bank of China (ICBC), China Construction Bank and Agricultural Bank of China.

Last week, Bank of China posted the slowest quarterly profit growth in three years, with net income up 5% to 34.8bn yuan ($5.5bn).

Non-performing loans fell to 0.94% at the end of June, from 0.97% at the end of March, although overdue loans grew by 17% in the first six months of year, suggesting that more loans may turn bad in the near future.

Mr Chovanec says many of the problem loans Chinese banks face stem from a state-directed lending spree in the wake of the global financial crisis in 2008.

The government leant on banks to lend more, particularly to local governments, which have used the cash for infrastructure projects intended to spur growth.

Last year, Beijing said that local governments had piled up 10.7tn yuan ($1.6tn) in debt, or the equivalent of 25% of China's annual economic output.

"Some were good investments and some were bad investments, but fundamentally they should have been paid with by tax revenue and they were not credible commercial loans," said Mr Chovanec.

Corporate angst

Companies too are suffering as a sluggish global economy hurts demand for the products China makes.

Small and medium companies, light manufacturers and wholesale retailers are driving bad loan figures, according to Sheng Nan, director for China bank research at CCB International, the research arm of China Construction Bank.

The problem is also geographical. Mr Sheng said that the steepest rise in non-performing loans has been in eastern China, particularly in Zhejiang.

The province saw a credit crunch last year as sources of informal lending dried up and sent scores of companies into bankruptcy.

However, he says it's unlikely that rising levels of bad loans will lead to a crisis in China's banking system given high levels of liquidity.

.jpg)

A clerk counting stacks of yuan at a provincial banks, where many hold bad loans

Unlike their counterparts in Europe and the US, Chinese lenders rarely need to tap wholesale funding from other banks.

They can rely on the vast flow of deposits from savers and companies, which usually have little option other than to park their cash with the country's banks.

"I am not denying that some of these loans are bad and I think the actual NPL number is probably higher than the reported numbers," he says.

"But the liquidity in the banking system is so abundant and as long as the liquidity and funding is there you can keep dragging the problem out.

"By doing this, you hopefully allow growth to absorb some of the problems - some of the projects that are not cash producing right now may eventually be profitable and you allow inflation to dilute some of the real value of the debt."

He also notes, so far, local and provincial governments have not had problems paying back loans that are coming due.

'No Lehman'

Mr Chovanec is more downbeat about the banking system's prospects - although he doesn't expect a major Chinese bank to implode Lehman Brothers-style given the state's far-reaching role in the economy.

"A bad debt isn't bad unless you insist on being repaid," he says.

"The (Communist) Party can call up the head of one the big four banks and say 'look just don't collect on these loans' but that still has economic consequences," he says.

"The core banking system can sit on top of bad assets for a long time but that drags down economic growth."

Mr Chovanec says it is plausible that up to 20% or even 30% of banks' loan portfolios will turn bad.

This means the money Chinese banks are required to set aside - 2.5% of the loans they have extended - would not be enough to cover loan losses.

He also says that many smaller Chinese banks may not have enough liquidity to allow them to keep rolling over loans until the economy improves and customers can pay back what they owe.

"Banks were reporting huge profits because they were lending a great deal and one of the reasons why they are reporting lower profits now is because they are lending less," he says.

"But all of this disregards the credit quality and whether they are going to get paid back on those loans."

- Published5 June 2012

- Published20 April 2012