Duane Jackson has gone from crime to company executive

- Published

Duane Jackson's company now has several thousand customers using his software

Spending more than two years in prison was an inauspicious start to becoming a successful entrepreneur. And Duane Jackson, 33, admits his conviction will always be a hindrance in business.

By his own admission he had a troubled childhood, and feels he was on a trajectory that meant imprisonment was probably inevitable.

The chief executive of accounting software firm KashFlow grew up in an east London children's home in Newham.

"I wouldn't say I fell in with the wrong crowd - I actually grew up with the wrong crowd," he said.

After difficult school years and being expelled twice at the age of 15, he seemed destined for a career in crime rather than becoming the founder of a firm that now employs 31 staff.

Social workers entrusted with his care were not trained teachers, so left him to his own devices with a ZX Spectrum computer and a user manual.

Drugs

In that time, he taught himself to write computer code. "With hindsight [it was] the best thing that could have happened to me." It was a skill that he built on and years later enabled him him to set up KashFlow.

Mr Jackson says there was a painful inevitability about his arrest, aged 19, for drug trafficking offences. He was detained in the US, but sent back to the UK for trial.

He said: "Growing up in children's homes, there is quite often a natural progression from there to prison... I'd be the odd one out if I wasn't involved with crime." About 27% of men in prison are estimated to have been through social service care before entering custody.

While behind bars Mr Jackson put his IT skills to good use and taught computing to fellow inmates.

Life after prison was not easy. Finding full-time employment was difficult, and he started working as a freelance web developer. Indeed, only about one third of people who leave prison go into education, training or salaried jobs.

As a one-man band doing his own accounts, Mr Jackson found that he could not get to grips with the "jargon" of the book-keeping software programmes available to small businesses.

Mr Jackson says teaching inmates business studies would help them survive on the outside

So he came up with an idea for a simple accounting system for owner-managers like himself. In 2006, four years after leaving prison, KashFlow was formed.

The company was established with money from the Prince's Trust, which provides help to young people wanting to start businesses.

But equally important was help he received from Lord Young of Graffham, an enterprise adviser to David Cameron and former Trade Secretary under Margaret Thatcher.

Not only did Lord Young become chairman of KashFlow, he invested in the firm. Mr Jackson said that getting the business and political heavyweight on board was a "big feat".

Mr Jackson had done some work for the London Youth Support Trust, and met Lord Young at an event organised by the charity.

He describes those early days when he was trying to get the business off the ground as "small steps and hard work". Six years on, KashFlow now counts the number of customers in their thousands.

With the struggles of launching a start-up now behind him, Mr Jackson nevertheless faces a different set of challenges.

The day-to-day running and expansion of KashFlow is still his focus, but his single biggest problem is recruiting the right staff, he says.

He was surprised to find that even many potential employees who have gone through higher education do not have basic skills.

"When I interview people who have got degrees, you find out they can't spell. It's a real struggle to find very good people," he says.

He has given work to ex-offenders, including one who has now gone on to bigger and better things. But Mr Jackson would never reveal names, as he knows from personal experience that the stigma of being an ex-con never goes away.

Criminal record

Mr Jackson says that his prison history will always loom over his business career.

Even basic formalities like asking for a bank loan present difficulties. The 'do you have a criminal record?' question always comes up. "As soon as you say 'yes' - you can see it in their face - there's no point," he says.

As his prison sentence was for trafficking drugs to America, he can never travel there again. There are entry visa restrictions, but also a lingering worry that the US authorities might even re-arrest him. "The US just isn't going to happen for me," he says.

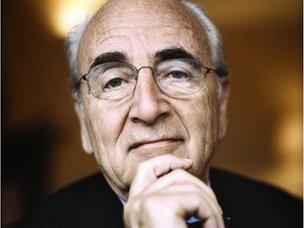

Lord Young of Graffham got involved after a chance meeting with KashFlow's founder

Mr Jackson believes strongly that enterprise should be used as a force for good - to help rehabilitate offenders.

In a blog post on the KashFlow website he says that prisoners should be encouraged to channel their energy and skills into business.

"There are lots of parallels between some forms of criminality and entrepreneurship… calculated risks, buying in volume and selling in smaller quantities at a higher price, dealing with competition, paying workers, strategic alliances," he said.

Inmates who show entrepreneurial flair should be given support to write business plans - and the most successful should be given funding to start their companies.

"Believe me, being locked away from society and your loved ones and losing your freedom is plenty punishment enough.

"If you don't give them help to get their lives back on track then they're only going to re-offend and cost society even more," he says.

Duane Jackson is, perhaps, the proof of that.