How banking culture transformed over the decades

- Published

Having a gold-plated reputation was paramount for bankers in the 1960s, says a former worker

"When I worked at Morgan, the place was so strait-laced I felt my pyjamas had to be pressed before I went to bed."

That's how a former senior banker describes the beginning of his career at JP Morgan in the 1960s, before the financial industry transformed into a giant global money machine.

It was a time when "protecting your bank's reputation was like protecting a woman's honour", he says, now retired.

How different it seems from today then, when the industry has become synonymous with society's ills - greed, immorality, recklessness - that have seen executives resign, bonuses clawed back and even a knighthood stripped.

"The general ethics at the banks are certainly not what it used to be," says another retired banker who worked at Citibank all his life, both requesting anonymity.

Charles Ponzi was one of the most notorious fraudsters of his day

Back then, he says, bankers "were well regarded. We were a prestigious industry having good principles."

The recent attempted Libor-fixing scandal, for example, is "disgusting", the former JP Morgan banker says, who also worked as a trader and as a Bank of America manager. "There was no reason to do that. It was just cheap - it's like hitting somebody when they're not looking."

Bankers in the past were not white-gloved gentlemen and the industry has not been without its share of scandals and miscreants.

The 1932 Pecora Commission investigating the causes of the Wall Street crash hauled before Congress powerful bankers such as JP Morgan Jr, the then SEC chief Richard Whitney, and a prominent commodity speculator Arthur Cutten.

Then there was Charles Ponzi of the same era, who has returned in the form of the American Bernie Madoff, whose pyramid scheme is the biggest financial fraud in US history. Fifty years later there was the Savings and Loans real estate scandal that involved five US senators along with the bankers.

So what changed?

'Financial archipelago'

"I think the traders became divorced from the rest of society and reality," says the retired Bank of America manager, who has traded on several continents.

"Managing a trading room is like running a sports team - you have prima donnas, you have to understand internally what's going on with your team, and then all the external politics, economics, market psychology. It's a very, very involved and interesting task. But it's gotten too complicated for people to understand the risks underwritten," he says, referring to the complex mathematics involved in trading and the alphabet-soup of financial products.

"When I began to trade you could deal with a client and then would watch his construction project or factory go up. Or you would cover somebody's car imports and see the cars in the parking lot the next day. A trader could relate to the real world," he adds.

As capital controls were gradually removed, large market swings became commonplace. "We made an awful lot of money out of volatility," he recollects. "It gave people the opportunity to make a lot money - but not to cheat."

The emphasis on short-term profit or 'short-termism' became full-blown by the mid-1980s when traders began demanding a share of their profits, who increasingly gained prominence.

Today, investment bankers and markets traders work on a "financial archipelago", a cloistered society that turns over billions of dollars each day, he says.

"The island has its own rules, its own standards and references. The fact is, after you start trading in millions and now billions of dollars, you have difficulty relating to real things.

"On top of that, you're only eating at the best restaurants, you only fly first class or in your private jet. You only talk to people of that level of society. You are probably not going to notice the cab driver or the cleaner in the office."

'Organisational spirit and loyalty'

The 'short-termist' mindset also became cemented by the disappearance of a group spirit and a sense of loyalty towards the profession, the retired bankers say.

"There was an organisational spirit in the old days. When you were working for Citibank you had to combine and work with the others in order to make Citibank look good. In my day if you joined Citibank you were expected to stay at Citibank all your life," says its former senior official.

That clubby spirit in the finance industry at the time was generally limited to a confraternity of well-educated men (often from the Ivy League, Oxford, or Cambridge), a world which excluded women and minorities.

But at least there was a loyalty among bankers towards the organisation and its long-term reputation, says the former Citi banker, who is re-reading an autobiography of his former boss Walter Wriston for the second time. That loyalty has persisted even as his professional career ended, as he is loathe to appear as a double-crosser.

"Now, people hop around from bank to bank without question. So the loyalty to the organisation is less than the loyalty to their own income and bonuses," he says, adding that it helped that banks in the past were more reluctant to fire employees.

According to Joris Luyendijk, an anthropologist and writer who blogs about the industry, external, most people jump jobs after being somewhere for between 18 months and three years.

"How people are fired and how they are hired says so much about (banking) culture. People may be gone in five minutes not just because they were fired but because they were hired elsewhere.

"So you are very atomised - you are on your own, trying to make money. There is a kind of culture of distrust, fear, politics that is created," he says.

"There is zero loyalty from your bank to you, zero loyalty from you to your bank. So during a crisis, the question of 'will this thing explode when I'm here?' is much more logical to ask than 'will this thing explode?'," he adds.

Bankers were also more obligated in the past towards their fiduciary duty - a relationship of trust - with clients, say former bankers.

"To say we always put the interest of the clients first was not entirely correct. But there was certainly in the past far more emphasis on sustained and continued relationships with clients," says the retired Citibank employee.

"We'd always regarded the bottom line, but we thought more about the profit going forward in the future," he says, adding that Goldman Sachs was the most egregious example when during the financial crisis its own traders allegedly bet against its clients for its own profit.

So how can culture change?

Mix of pressures

Following the series of scandals, banks are trying to clean up their image and win back public confidence by firing the old guard and bringing in new faces.

But it is no easy task.

"Once you bring in a fresh leadership it will audit new leadership. But culture does not change overnight," says Melissa Fisher, a professor of anthropology at New York University who recently published Wall Street Women, a book about the history of women in finance.

"These are structures of power and culture that are deeply ingrained. You can't just change the formal rules - there is a difference between what people say and what they do. How to create a new structure from top to bottom takes time."

Banks will also need to create change from the inside by protecting whistle-blowers, says Mr Luyendijk.

"You don't fix Libor over a decade without lots of people knowing. Still, people don't speak out. And they don't because they are under-protected. There seems to be a real correlation between job security and doing the right thing and thinking long term," he says.

One senior regulator told him: "I'm not worried about bankers lying to me, I'm worried about bankers lying to themselves."

But change can be done.

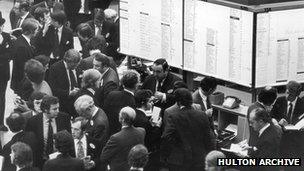

Women and foreign-born members were barred from the floor of the London Stock Exchange until 1972

One prominent example is how women financiers tackled a culture of chauvinism and discrimination in the industry, transforming it into what is a more diverse community today.

Since the 1950s women have tried to break a glass ceiling faced with the knowledge that complaining to their superiors would have had them fired, says Ms Fisher.

So they created their own support network - the first Financial Women's Association in New York was set up in 1956 with just eight members - tasked with changing culture "slowly, incrementally, individually and as a group".

"I'm a proponent of both outside and inside (pressure) groups," says Ms Fisher.

"Cultural change can come from multiple strategies - there's no one way to catalyze change. But even having a space for people to talk is important - because talk can lead to action. If you are all having the same issues you may catalyze that into change. It's important to have spaces that are created outside the formal structure," she says.

'Greedy pensioners'

But financiers are not the only ones to blame.

Banks are under pressure by investors and shareholders such as pension funds to make money, or else they will shift their investments elsewhere.

"So there's a lot of greed, but also greed in their part," says Mr Luyendijk.

"If pensioners told the funds: 'Look, I am willing to have a little less pension if the bank is behaving', then I think that would really make a change. But I think that's where it stops. I think it's really comforting to shout at the bankers, but ultimately their behaviour is a more extreme example and a more visible example of everyone's behaviour," he says.

"Bankers are not the only ones being short-termists and selfish."

- Published3 September 2012

- Published29 August 2012

- Published26 July 2012