Dutch vent frustrations at euro

- Published

Twenty years ago, European leaders gathered at Chateau Neercanne

Pieter Harkema was there when the euro was born.

He runs Chateau Neercanne, the venue on the outskirts of the southern Dutch town of Maastricht, where 20 years ago European leaders gathered to agree the treaty that created the European Union and paved the way for the euro.

German Chancellor Helmut Kohl, UK Prime Minister John Major and French President Francois Mitterrand toasted their agreement to pursue European Monetary Union over a lunch of lobster in a lemon and courgette chutney, followed by pheasant.

"It was a very special lunch," says Mr Harkema.

These days though, the fizz seems to have gone right out of the euro project, even here in Maastricht, and the Dutch will have a chance to vent their frustration in Wednesday's general election.

The Netherlands is a core eurozone country that has always been at the forefront of European integration.

The polls matter because they will decide whether the country will remain Germany's ally in the fight for fiscal discipline across the eurozone, or whether an increasingly frustrated Dutch electorate will vote for parties that could redefine the Netherlands' ties with the European Union.

EU bureaucracy

Harry Meens, owner and director of Alfa Beer, a family brewery outside Maastricht, says: "I have a pile of papers, 2m [6ft 6in] high, full of regulations and rules about how I should be running my business."

Like so many Dutch voters, he resents what he sees as the EU's heavy bureaucratic hand in the domestic affairs of the Netherlands.

Ten years of the euro "has done nothing for me and my business", says Mr Meens. In fact, he says, Alfa Beer used to export to the UK and the US - but with the introduction of the single currency, those exports became more expensive and the orders from overseas stopped coming in.

"We have one Europe with totally different excise duties and taxes in each country. It doesn't work," he says. "First work on harmonising all that and then create a single currency. They did it the wrong way round."

Dissatisfaction

His eurosceptic stance is perhaps surprising for a business that operates in Limburg, a province many see as being at the heart of Europe.

It is easy to see why the Maastricht Treaty was signed here. Limburg is a small lip of land in the south of the Netherlands, flanked by Belgium and Germany.

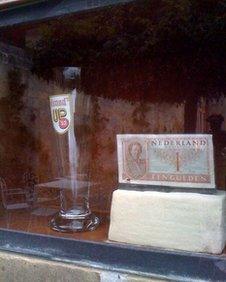

The old Dutch currency, the guilder, has not been forgotten

But the sort of dissatisfaction expressed by Mr Meens is one of the factors that has ensured the recent rise in popularity of the People's Freedom Party, led by its firebrand anti-immigration, anti-euro leader, Geert Wilders.

It has also ensured a rise in popularity for the Socialist Party (SP).

"Over my dead body," is what the SP's leader, Emile Roemer, answered when asked if the Netherlands should pay fines to the EU in Brussels for missing targets on cutting spending. It greatly helped his popularity in the opinion polls.

That is because the Netherlands is battling with pension reform and rising healthcare costs, all issues which are being driven by a pledge to meet EU budget targets.

What makes those planned cuts particularly galling for many Dutch people is they come as the Dutch are being asked to foot the bailout bill for southern European neighbours such as Greece and Spain.

Mr Wilders wanted to turn the election into a referendum on Dutch membership of the euro and the EU, denouncing the heavy burden carried by Henk and Ingrid, his Dutch stereotypes of Mr and Mrs Average. His campaign backfired when a real-life Henk with a wife called Ingrid attacked and killed an immigrant.

Exaggerated importance?

To date, Germany's Chancellor, Angela Merkel, has been able to rely on the Dutch as an ally around the eurozone negotiating table, ensuring Berlin is not isolated in its calls for fiscal austerity in Europe.

For some, the concern is that the elections might return a Dutch government more critical on eurozone and EU matters.

Still, Johan Muyskens, professor of economics at Maastricht University, thinks that gives the Netherlands an exaggerated sense of importance on the European scene.

"Economically speaking, we are just one of the states of Germany, basically," he says. "That's the economic reality."

He also points out the Netherlands always ends up with a coalition government made up of at least three political parties. That means that any anti-euro or anti-sentiment inevitably gets diluted.

"Most business people think it's impossible that the euro would disappear or anything like that," says Wil Houben, director of the Limburg Chamber of Commerce.

But that does not mean that there isn't any nostalgia for the old Dutch currency.

Back at Chateau Neercanne, where the euro was born, manager Pieter Harkema points to a small tower on the chateau's terrace. It is a restaurant called The Guilder and it seems to be doing a roaring trade.

- Published13 September 2012

- Published11 September 2012

- Published11 September 2012

- Published11 September 2012