Your flexible Fed

- Published

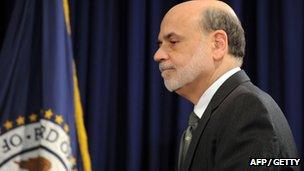

Ben Bernanke's new approach is a deeply significant shift

For several years the US Federal Reserve has pioneered what might be called the "straitjacket" approach to setting interest rates.

But when it comes to injecting money into the economy, this latest decision has it embracing an equally unprecedented amount of flexibility.

The straitjacket comes in the promise - made repeatedly in recent years - to hold official US interest rates at today's very low level, for a minimum period of time. Whereas the Bank of England's policymakers like to say they judge policy "month by month", the Fed has explicitly sought to push down long-term interest rates by promising that rates will not go up before some specified date.

Before this latest meeting, the promise had been that interest rates would not rise before the end of 2014. As expected, that has now been pushed back, with the Fed statement suggesting that rates will stay close to zero until at least the middle of 2015.

That is not as long as some were expecting, but there is also, for the first time, a suggestion that rates will stay very low, even after that: "A highly accommodative stance of monetary policy will remain appropriate for a considerable time after the economy strengthens."

This is being interpreted by some as a suggestion that that the Fed might allow inflation to go above target in the early period of recovery, just as it went below 2% in the worst part of recession.

But, of course, the most significant part of the statement was not the interest rate commitment but the new promise, in effect, to spend $40bn (£25bn) a month until unemployment gets significantly lower.

This was widely anticipated, after Ben Bernanke's remarks last month at Jackson Hole, but it was not a done deal, before Thursday's meeting - and it marks a deeply significant shift in the Fed's approach.

In effect, the Fed's policy committee is now saying it truly will "do what it takes" to bring US unemployment down. There is no pre-announced limit to "QE3". It will sail indefinitely, and it will be the state of the real economy - particularly unemployment - that will largely set its course.

Republican critics on Congress and general inflation "hawks" will not like the idea of the Fed creating yet more money - possibly another $1.4tn or more, if it continues to buy bonds right up until the middle of 2015. That's on top of the $2.3tn the central bank has already spent, in its various rounds of quantitative easing.

Critics outside the US will also question whether the policy will be effective, and worry about the distorting effect it might have on the value of the dollar and global commodity prices.

But, these worriers will presumably like the fact that the monthly amount, $40bn, is less than many had expected. And they may well like the fact that the purchases could stop, at any time, after the end of the year.

In that sense, the new "flexible Fed" has something to offer the doves and the hawks. Doves will like the fact that there's no expiry date, while hawks like the fact that the Fed can throw it out at any time.

So far, the financial markets seem to be pretty keen on the Fed's new promises, as well.

But with the economy at the top of the US political agenda, the central bank is surely not going to please everyone with this new approach. Nor - given all the uncertainties hanging over US fiscal policy and the global economy - has it necessarily found the key to unlock America's jobs market.