Fertility trade: Eggs, sperm and rented wombs

- Published

The growth of the fertility industry has meant women's eggs and men's sperm have become commodities like any other, to be bought and sold.

Along with rented wombs, it's a sign of an industry benefitting from the trend for working women to start their families later, when they might have more problems conceiving.

If a woman can no longer produce her own healthy eggs, she might go to a clinic which offers donated eggs, to be fertilised by the husband's sperm and then implanted.

"The demand is quite excessive," says Amanda Segal at the Shady Grove Fertility Reproductive Science Center near Washington DC in the US.

"With a donor egg, they are still a part of their partner if they are using their partner's sperm," she says.

"And she gets to carry their child."

Advertising for donors

In some countries, the law allows women who donate eggs to be paid for their services.

"At the Shady Grove Fertility Centers, we cap it at $6,500 (£4,000)," says Ms Segal.

Donors have to be between the ages of 21 and 31 and the centre advertises on Facebook and Google to target young women.

"In any month, we probably have about 1,000 applications," says Ms Segal. "Out of those 1,000, only 5% make it to egg donation."

The purchaser can end up paying about $25,000 once the pre-screening procedures, medicating the donor, and the fee paid to the donor for her eggs are taken into account.

But Shady Grove Fertility does offer a full refund if no baby is delivered, no matter how many cycles are involved.

Ms Segal recognises that some people might think it distasteful that women's eggs, the source of all human life, have become a commodity to be bought and sold like any other.

"When you are on the other side of the fence," she says, "you immediately realise what a gift this young woman (the donor) is giving."

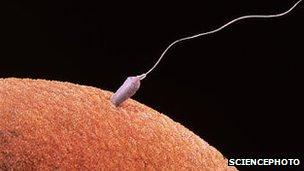

Also in demand is donated sperm. Figures suggest that 10% to 15% of all heterosexual couples have trouble conceiving and many single and gay women are also opting to have babies using donated sperm.

One of the biggest exporters in the world is Cryos International in Denmark. Its service allows customers to bypass strict regulations which control the supply of sperm in clinics in many countries by having products shipped directly to people for home insemination.

Managing director Ole Schou says lesbian couples make up about 10% of their clientele, with single women accounting for about 40% of demand. "It is like an avalanche, a tsunami," he says.

Online browsing

He notes that they tend to be highly educated, well-situated females who have focused on their career and then, in their 30s, start thinking about reproduction.

Unlike obtaining sperm from a fertility clinic, which has acquired it from a sperm bank, Cryos International enables customers to browse online to choose the donors which suit their needs - essentially shopping for a father.

"I don't like the word father, we call it a donor," says Mr Schou, "But yes, you can choose between the different types of donors and the different qualities."

In some cases, the customer knows who has donated the sperm, although rules determining the identity of the donor vary from country to country.

Sperm is also tested, selected and screened according to different rules.

Standards in the US are determined by the Food and Drug Administration, while in Europe there are the Tissue Directive standards.

"We also have different quality in terms of concentration - the concentration of motile sperm per millilitre after thawing," says Mr Schou.

Prices for 0.5ml of sperm range from $50 (£30) to $500.

Exploitation?

Another, more controversial way, for infertile couples to have a baby is through a surrogate mother.

Sperm from the man can used to fertilise his partner's or a donated egg. A surrogate is then paid to carry the child until it's born.

The practice is not illegal in the UK, but it is restricted by various legal rules which, generally speaking, allow only surrogacy arrangements that are informal and non-commercial.

But in some countries, including India, it is legal and offers poor women an opportunity to make what for them is a large amount of money. But it also raises the question of whether they are being exploited.

On average, a surrogate at the Ak-shanka clinic in Anand in Gujarat state will get $7,500, or up to $10,000 if she is carrying twins.

On top of that, explains Dr Nayna Patel, who runs the clinic, they will be compensated for not working, and their food and accommodation is paid for during pregnancy.

Surrogates live in a house owned by the clinic throughout the pregnancy, although they can go home for a brief spell or in case of an emergency.

However, Dr Patel points out: "Most of the time we would like them to stay with us, just to take care of their health."

Thought is given to the psychological effects on surrogates who have their babies taken away from them soon after birth. "We never take a surrogate who does not have a living child of her own."

While in the surrogate house, they get lessons like a beautician's course, embroidery, tailoring, and spoken English.

"Even after finishing surrogacy, they come back to the house for the free lessons," says Dr Patel. "If you want to say it's a baby factory, fine. If you want to say that it is helping the women change their lives, it is another way to look at it.

"It could be enough to buy even a house or educate her children. I have records of what the surrogate does with the money - if they buy a house or a piece of land, they give me all the details, the documents, and I think that that is extremely satisfying," she says.

- Published13 April 2012

- Published21 December 2011